We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Dale Vince, the green oligarch and wind turbine tycoon, is suing Guido Fawkes for reporting what he said about Hamas on Times Radio when he compared the Hamas terrorists to freedom fighters.

Dismal tax trougher Vince is suing the editor Paul Staines personally for daring to publish the actual words Vince said in an interview with the Times Radio’s Stig Abell.

This is pure distilled lawfare and for the first time in 20 years Guido is asking contribution to their legals costs. As a longtime fan of Mr. Fawkes, I have chipped in and I urge anyone else who dislikes the Green Mafia to do likewise here.

The mainstream press is 99.9 percent captured.

The “gatekeepers of the news” have become stenographers of virtually every dubious or false public health narrative. Nobody (who really matters in the Big Picture) is challenging the never-ending lies, manipulated data and false narratives.

If this lack of skepticism persists, it seems almost a certainty that all the important organizations in the world will continue to be led by people who either aren’t intelligent enough to challenge false narratives or know the narratives are false and simply don’t care.

– Bill Rice

Myers clearly regards Bridgen’s claim that the mRNA vaccines may be doing more harm than good to be nonsense, but in fact it is well-supported by evidence. For instance, British Medical Journal Editor Dr. Peter Doshi along with Dr. Joseph Fraiman and colleagues examined the data from the vaccine clinical trials and found that, compared to controls, the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccines were associated with an increased risk of serious adverse events of 10.1 events per 10,000 vaccinated for Pfizer and 15.1 events per 10,000 vaccinated for Moderna. When combined, the mRNA vaccines were associated with an increased risk of serious adverse events of 12.5 per 10,000 vaccinated, or 1 in 800. Note that the adverse events they looked at included those from COVID-19 itself, meaning the findings imply that among trial participants the vaccines were doing more harm than good.

Similarly, Dr. Kevin Bardosh and colleagues – hailing from the Universities of Harvard, Oxford, Johns Hopkins, Edinburgh and Washington, among others – found that for every COVID-19 hospitalisation prevented by boosters in previously uninfected young adults, 18 to 98 serious adverse events occurred, including 1.5 to 4.6 cases of booster-associated myocarditis in males. That’s more harm than good, at least for healthy young adults.

– Will Jones

Nice fisking, read the whole thing.

I have recently started a YouTube channel. It is called What the Paper Said and – as I say every week in the introduction – involves me skimming through The Times from a hundred years ago, picking out some of the articles and commenting on them.

So, if you are into fascism, communism, socialism, hyperinflation, genocide, civil wars, kangeroo courts, unemployment, deadly diseases, non-deadly diseases, smog, alcohol prohibition, cocaine prohibition, compulsory vaccination, dirty old Clerks to the Privy Council, the Ku Klux Klan, American spelling, imperialism, railway statistics, rent control, aging battlecruisers, some bloke called Hitler, and Oxford commas; this may be the channel for you. Until it gets banned.

Also available as a podcast.

I have written here about the #GamerGate phenomenon before, which was a series of rolling online flash mobs, events and activist commentary mostly doing its thing circa 2014-16. This was kicked off by something specific but quickly evolved into a far wider reaching grassroots pushback against rampant corruption, collusion and ever more woke politicisation in games ‘journalism’ and indeed games themselves.

Naturally the gaming press harrumphed with indignation, howling that GamerGater was an unconscionable harassment campaign; its largely nameless supporters all racist/sexist/homophobic. And much to their shock it didn’t work. GamerGaters ridiculed their evolving official narratives. And to the PR wonks working for MSM publications and their assorted vassals, none of it made any sense, which is why they still make sure the preposterous Wikipedia entry conforms to the official narratives (i.e. very little relation to reality). Too bad guys, you can’t bomb a hashtag.

GamerGate was something that drove (and still drives) many people insane, living rent free in their heads for years. Even now, the mere sight of GamerGate mascot Vivian James (video games, geddit?) can cause hilarity and rage in certain people.

Fast forward to 2022 and behold #NAFO: the North Atlantic Fellas Organisation.

And who are ‘the fellas’? A large and growing online pack of attack dogs countering, dare I say smothering, official Russian troll factory output, as well as other pro-Kremlin talking heads online. And their mascots are daft cartoon dogs (variations of a Shiba Inu to be precise). If journalistic collusion was a constant target of #GamerGate, the Russian troll farms are the modern analogy to that, constantly targeted and smothered by NAFO posting either pro-Ukrainian counter-narratives or just ridiculing or flagging up pro-Russian ones.

Many people, particularly those operating within institutions, don’t understand #NAFO for same reason PR departments of various video games companies & press outlets didn’t (and still don’t) understand #GamerGate.

Is #NAFO engaged in ‘information warfare‘? Absolutely. They even get a shout out from the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence. But they are not managed out of an office in Langley, Virginia nor by some adjunct of the Ukrainian intelligence services. #NAFO is a hashtag, a phenomena, it isn’t “run” by anyone, because it doesn’t need to be. Like GamerGate, NAFO is a confluence of the motivated willing in every timezone on the planet.

And just as GamerGate had a single original trigger, which was then largely forgotten as the ‘movement’ grew and started attacking larger more juicy prey, NAFO started as a fund raising effort for the Georgian Legion (a now battalion sized unit of about 600 within the Ukrainian army made up mostly of Georgian volunteers). At blinding speed, NAFO rapidly morphed into a wider distributed online effort supporting Ukraine in the “information space”.

NAFO… daft, puerile, bonkers, pervasive. But it works.

Journalism is something you do, not something you are.

– Glenn Reynolds

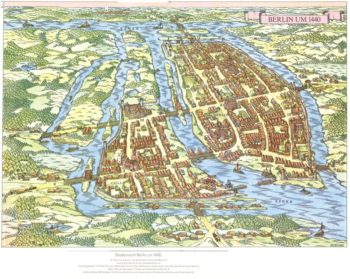

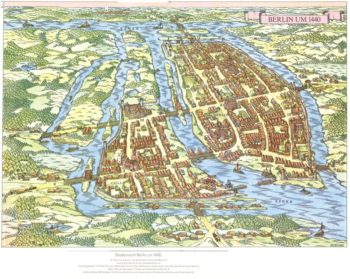

From the ever-brilliant Kristian Niemietz

Click for slightly larger version

“The draft Online Safety Bill delivers the government’s manifesto commitment to make the UK the safest place in the world to be online while defending free expression”, says the gov.uk website. It would be nice to think that meant that the Bill would make the UK the safest place in the world in which to defend free expression online.

The text of the draft Bill soon dispels that illusion. Today’s Times editorial says,

In the attempt to tackle pornography, criminality, the promotion of suicide and other obvious obscenities rampant on social media, the bill invents a new category titled “legal but harmful”. The implications, which even a former journalist such as the prime minister appears not to have seen, are worrying.

It is sweet to believe the best of people, but that “appears not to have seen” is either sweet enough to choke on, or sarcasm.

Could they give the censors in Silicon Valley power to remove anything that might land them with a massive fine? That would enshrine the pernicious doctrine of no-platforming into law.

Fraser Nelson, editor of The Spectator, has expressed alarm at what he fears the wording could do to his publication. Any digital publisher who crossed the line might find an article on vaccine safety or on eugenics, or indeed any topic deemed controversial, removed without warning, without trace and without recourse to challenge or explanation. The decision would not be taken by human beings, but by bots using algorithms to pick up words or phrases that fell into a pre-programmed red list.

The editorial continues,

The bill specifically excludes from the category [of “legal but harmful”] existing media outlets. If Facebook or another platform took down an article from a British newspaper without explanation, Ofcom, the media regulator, could penalise the platform.

That’s us bloggers dealt with then. Notice how the article frames the threat to free expression almost entirely in terms of its effect on newspapers. Still, in the current climate I am grateful that the Times has come out against the Bill. If self-interest is what it takes to wake them, then good for self-interest.

However, social media giants operate on a global scale. In any market such as Britain, where they have a huge following and earn billions, they will not risk a fine of 10 per cent of their annual turnover. They will simply remove anything deemed “harmful”, or, to counter the bill, downgrade its visibility or add a warning label. Given that America’s litigious culture will influence those deciding what constitutes harm, this could include political assertions, opinions or anything the liberal left could insist constitutes “fake news”. If Donald Trump can be banned, so can others.

As promised.

By the way, I found this rather good obituary of Brian by Sean Gabb at The Critic.

Update. The post was initially put up with the wrong link (hence Paul’s comment). It has now been corrected.

It has been a long and crazy ride, but we are still here snarling, laughing, bloviating and pondering 20 years later.

In these increasingly intolerant times, never have independent sites been more needed than now.

Our late colleague and friend Brian Micklethwait was very good at making people think. In particular he was very good at making me think, and even at times making me write. Often he would say something interesting that would make me write something as a response that I would never think to write for any other reason, and this blog, his own blog and its predecessors are full of articles and comments that were responses to things he started me thinking about. He had a tendency to repost my comments as articles when he found them particularly interesting, and many of our conversations took place in the articles and comment sections of various blogs. He loved posting photos of quirky things, fascinating objects, major pieces of architecture and engineering and interesting maps of places around the world that looked like they might be interesting.

Brian was not a great traveller. He was very pro-American, but he never visited the United States. He had done some travel earlier in life – including some behind the Iron Curtain before it fell, which I wish I had been able to do – but in the final two decades of his life when I knew him, he only ever really left London for regular summer trips to visit some friends in France. He clearly enjoyed this immensely, but travel was too much of a hassle for him unless there was warm hospitality as well as good company at the end of it.

He did, however, inspire me to travel. I saw photos of interesting things on his blog, and I researched them and wanted to go there, and I often did. He found this amusing, but he also liked to talk about what I had seen and photographed with me, so this continued the thoughts and conversations. (I still haven’t been on the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, alas, although I have been on the similar but not quite as spectacular Matheran Hill Railway south of Mumbai).

In any event, in March this year Brian posted a pictographic map of Berlin in 1440 that he knew nothing of the origins of Berlin, but that he found the map interesting, showing a town or small city on two islands in the river Spree with a third island on the left that was at not that point significantly populated. As it happened, I knew relatively little about the origins of Berlin either, but I was instantly curious. I have been to Berlin many times, but I couldn’t have told you where the original town was. (Actually Berlin was technically two towns at the time – Berlin on one island and Cölln on the other). So I researched it, and discovered that although Berlin had some medieval city walls, these had not protected the city well in the Thirty Years War. The relatively unfortified city had subsequently been fortified into a star fort between 1650 and 1683, at which time the two outer streams of the river surrounding the three islands had been turned into a moat and the inner banks replaced with high walls. These walls then subsided into the swamps on which Berlin was built and were torn down starting in 1734, after which the two outer streams of the river were filled in, leaving only one island. The route of the north-easterly wall/stream was eventually used as the route for the Stadtbahn – Berlin’s main east-west railway. The south-easterly route, well, it was filled in and replaced with a layout of streets. Where it was is not obvious on a map or in a photograph.

I also found some modern maps and photographs of Berlin, and sent them to Brian. The inner island, the Spreeinsel, is recognisably the same between the oldest map and the newest photo, and does still have some remnants of being the important centre, including Berlin’s protestant cathedral, but the northern half northern half of it became the site of Berlin’s greatest museums, many of which have been reconstructed in recent times and restored to something even beyond their pre-WWII glory. In the comments, further conversation ensued. More people got involved in the conversation.

Inevitably in all this, I booked a trip to Berlin to wander around and look at the city from this new (or old) perspective. This was originally booked for April 2021. This was optimistic on my part given the circumstances, but I have actually done a lot of optimistic booking of travel over the last 18 months, the vast bulk of which has subsequently been rebooked, postponed and/or cancelled. (Lots of things have been ludicrously cheap to book due to travel companies promising anything in return for being given even small amounts of money, and have then been deferred to the indefinite future. Hopefully these companies will not now go bankrupt when they are forced to catch up with their liabilities). In any event, this trip was postponed to this month.

And, well, on Friday October 15 I got on a plane having received the awful news earlier in the day that Brian had died that morning.

Trying to find old things in Berlin is a struggle. There was a fairly small town there in 1400, but since then it has been drained, expanded, made a provincial capital, rebuilt, fortified, invaded once or twice, expanded again, demolished, rebuilt again, expanded some more, fortified, rebuilt again and turned into an imperial capital, torn down, blown up, bombed to rubble, blown up some more, turned into a communist capital, demolished again, neglected, expanded some more and rebuilt again and made into a national capital, just giving he highlights. In most cities, the geographical and historical bones stick through. In Berlin, much less so. The watercourses to some extent, but that is all.

I attempted to look for remnants of the old city walls. In most cities it would be helpful to type “[City Name] wall remnants” into Google, but “Berlin Wall Remnants” gets something else. To make things even more complicated there was another wall, the Customs Wall, that was built around 1737 for tax collection purposes (boo). Most Berlin place names refereeing to gates (most notably the Brandenburg Gate) refer to this wall. So, I actually found myself looking at the original maps of Berlin in 1440 (and the later map of the star fortress in around 1683), looking carefully for the rights bends and branches and former branches of the river. I started well, finding a piece of (obviously restored) medieval city wall in Littenstrasse>. But that was it for finding further pieces of wall. I followed the approximate line of Littenstrasse through Alexanderplatz, just to the south of the Stadtbahn along the top of what had been Alt-Berlin.

The street plan had been changed by the centuries and the Prussians and the fascists and the communists, and I found nothing more medieval. I crossed the Spree at Bodestrasse, between the Neues Museum (now again containing the bust of Nefertiti, as it did before 1939) and the Berliner Dom, the now restored protestant cathedral that had still been in post-WWII ruins when I first visited Berlin in 1992. I then doubled back to the top of the island before walking past the Humboldt University of Berlin, through Bebelplatz (site of the Nazis infamous book burnings), past the Roman Catholic St. Hedwig’s Cathedral (at present closed for the East German post-war modernist restoration to be removed and replaced with something more tasteful and less full of asbestos) and Oberwallstrasse, Niederwallstrasse, and Wallstrasssse, the latter three streets following the route (with a little straightening) of the wall of the star fortress, at least some of the bends in the shape of that wall being apparent. And back where I started, but on the other side of the river, having circumnavigated the old cities of Berlin and Cölln.

But there was one more thing to see. When we were looking at old and new pictures of Berlin, Brian’s cousin (I think) David Micklethwait commented that the only building that could be seen in the first, last, and intermediate pictures of Berlin was the Berliner Schloss (Berlin Palace), originally the Churfurstl Schloss (Elector’s Palace), home of the heads of House of Hohenzollern during their long journey from Margraves of Brandenburg to being Emperors of Germany before Kaiser Wilhelm II was forced to abdicate in 1918.

Except, I did some further research and it is stranger than that. Rather than being the oldest building in the later photo of Berlin, the Berliner Schloss is actually one of the very youngest – the current building was completed in 2020. The original building was badly but not irreparably damaged in World War 2. The East Germans at times used it as a backdrop for a War movie (including firing live ammunition at it), partly repaired it and used it as office space, denounced it as a symbol of Prussian militarism, and finally demolished it in 1950, partly for ideological reasons but mainly because they were arseholes. The Palace of the Republic – the East German parliament – was then built on the site. After German reunification in 1990, the new German government demolished this building, partly for ideological reasons and partly because it was full of asbestos.

After much discussion, the Palace was rebuilt as the Humboldt Forum, a museum featuring a reconstruction of the Berliner Schloss on the exterior but with an entirely modern interior. (The result was then denounced by the New York Times as an attempt to hide the history of Prussian militarism). Brian found this amusing, as it fitted in with another of his ideas – the triumph of modernism on the insides of buildings but not so much on the outside. His recent thoughts on this subject came in the context of hospitals, alas.

So, I finished my walk around old Berlin with a visit to the Berliner Schloss / Humboldt Forum. And, well, it’s weirder than that.

If you are going to reconstruct old buildings after a war, there are a few things you can do. You can take what is left, and use modern techniques and designs to rebuilt the rest, leaving you with a building that is half and half new and old. (Lots of buildings in Britain and for that matter in West Germany that were quickly rebuilt after WWII are like this). You can reconstruct the new parts in hopefully a sympathetic and complementary style, but also in such a way that the new bits are obviously new rather than old. (Much of the recent restorations of central Gdansk are like this, and I like them a lot). You can attempt to restore the damaged part of the building to the same design as before. The aforementioned Berliner Dom is an example of this. Or you can demolish the ruins and start again, either in the same style or differently. Rebuilding exactly what was there before (as was done in the centre of Warsaw) perhaps works if you do it right away (as the Poles did) but the longer you leave it, the more the result looks like trite and artificial, at least at first. (For an example, look at the Dresden Frauenkirche. It’s a brand new Baroque building with no wear built to modern health and safety standards)

And well, the architects who rebuilt the Berliner Schloss decided to make the fact that it is a reconstruction obvious, by building the front wall (including the main entrance) and two side walls as perfect reconstructions of the original down to every detail, but the back wall in a rather severe modernist style. Similarly, the main courtyard has three interior walls in the Prussian Baroque style of the original building and one in modernist wall. If you look at the building from the front or the sides, it looks like an (admittedly brand new) Prussian Baroque palace. From the back, it looks like a modernist building. From other angles, it looks mostly like an old building, but not quite.

Does it work? I’m not sure. It would have no chance of working anywhere other than in the strange city of Berlin, which is a mix of old and new and original and reconstructed and broken and repaired and has been a showcase of every German regime for the last 500 years – for good or for bad.

A month ago, and a year ago, and ten years ago, and twenty years ago, I would have talked about all this with Brian when I got back. I might have e-mailed him photos when I was still there. There would have been more sharing of photos and conversing and commenting on blogs. He might well have called me an idiot if I said something I disagreed with. I have no idea whether he would have liked or disliked the rebuilt Schloss Berlin, but he would have had something interesting to say about it. He loved talking about what buildings looked like in the context of the surrounds of the cities they were in, and found that too much architectural commentary didn’t focus on this and instead talked about buildings in isolation. I agreed with him on this point, which is one reason why I go places to see stuff.

Anyway, the point is that I miss Brian. Fuck cancer.

Brian Micklethwait departed this world earlier today, leaving the samizdatistas poorer for his absence but richer for his lifetime dedication to the cause of liberty.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|