We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Yesterday I sent out a mass email to a list of my nearest and dearest, as many of them whose names I could remember, telling them that, just before Christmas, I had been diagnosed with lung cancer, and you know, pass it on. I said how bad I thought it was, and it does indeed seem rather bad. And I said what they could all do to cheer me up. Basically, tell me and tell the world what a clever fellow I have been over the years, and what their favourite writings and activities of mine have been. This process is now well under way, and a very gratifying boost to my morale it has already been, morale when faced with cancer being, I surmise, a rather big deal, maybe even a life-saver. My thanks to all those who have already communicated with me along those lines, and long may that process continue.

I put the entire text of that email up at my personal blog, and should you now wish to, you can read it there.

What else to say? Many things, not least that this diagnosis has concentrated my mind wonderfully on what really matters to me. During the last few years, I have found myself writing more and more about trivia and esoterica, of the sort that intrigues me but lacks general appeal, at my various personal blogs, rather than trying to grab the world by the ears here at Samizdata. Although I promise nothing, I now feel that this is liable to change. My life now looks like being too short to be postponing the final bits of ear-grabbing that I now want to try to get done, before I depart. Famous last words are hard to contrive, but some rather more impressive ones than would have happened had I merely died suddenly now seem worth attempting.

I’ll make a start by writing about a phenomenon I have become very aware of during the last few days and weeks, which is the imbalance between the effectiveness of Britain’s National Health Service when it comes, on the one hand, to the diagnosis of a disease, and on the other hand, to the treating of it.

Basically, the NHS does the first very inefficiently and in particular very slowly. But, it does the second really rather well, often just as well or better than the private sector, and often with the exact same equipment and staff.

My understanding of this contrast may be distorted by the fact that I am now being treated, at the expense of the NHS, at London’s Royal Marsden Hospital in the Fulham Road, which has a global reputation for its cancer treatment. But, in not a few of the sympathetic emails I have received from friends and relatives, this same story has recurred, of slow and unsatisfactory NHS diagnosis, then followed by a vigorous, urgent and targetted response to the problem, once that problem was properly understood.

The email which explained this best came from my sister, who was an NHS General Practitioner for all of her working life until she retired.

The problem faced by the NHS in diagnosis is that the NHS is confronted on a daily basis with an ocean of complaints about aches, pains and general misfortunes which can be anything from very serious to hardly counting as real medical problems at all. NHS general practitioners provide a service which stretches all the way from trying to spot something like my lung cancer, to just lending a sympathetic ear to a person who is being tormented by her husband or children, or just generally feeling glum and run-down. The service is free at the point of use. If you are having a miserable life and could use some pills to take the worst of the sting out of that life, and if you would positively welcome waiting in the queue at the doctor’s, thereby enjoying a little moment of blessed relief from the disappointments or even torments of the rest of your life, well, you would visit your doctor, wouldn’t you?

The National Health Service doubles up as a sort of National Friendliness Service. At which point, how is the doctor supposed to decide who he or she should spend serious time with, in this vast and varied queue, and whom he or she should shove to the back of the queue? How is the doctor supposed to spot the serious medical cases, in among the vast throng of the merely unhappy and unfortunate? I’m not blaming these NHS doctors for their problem. They’re doing their best. It’s just that their best is liable not to be that good.

So it is that the NHS takes a huge amount of time to identify the serious cases, such as mine is. A pain in your pelvis, you say? Quite bad, you say? Well, I suppose you could have a test, towards the end of next month. Maybe an appointment with a bone doctor, in January? Would the 21st be convenient? Our budget is rather limited, as I am sure you realise, and time slots soon get taken.

Faced with this interminable process, while my aches and pains gradually got that little bit worse as the weeks went by, I eventually sought the informal help of medically expert friends. Who immediately advised me to go private to find out what the problem was. Sounds like it’s serious, they said. They recommended a trusted private sector GP, who talked my sufferings over with me on the phone within about one hour, and immediately steered me towards an esteemed colleague. I put myself in this colleague’s hands. I did not and still do not have any private medical insurance scheme. Nevertheless, for the price of a cheap second hand car, I then learned the bad news of what was happening to me in a matter of days. In no time at all, or so it now feels, I began to be treated at the Royal Marsden, for the immediate threat to my spine, which is just next to where the tumor is.

I soon realised that what I had paid for was not just a diagnostic expert, but also an advocate for me, within the NHS system. That advocate could lay out the evidence in front of the NHS. Look, this is serious. Treat this, and you won’t just be chucking money at nothing. You will be curing or at the very least seriously treating a serious condition.

I am not trying to make a partisan political point here. I know I know, NHS equals socialism, yah boo hiss. But I think the distinction is a bit more subtle than that. As I say, the serious treatment of serious conditions bit of the NHS seems, if my experience and that of other emailers to me in recent days is anything to go by, to work rather well.

I think the distinction concerns what in other contexts is referred to as “moral hazard”. It is one thing to exaggerate an ache or a pain in order to have a nice little conversation with a nice doctor and to get hold of a few prescription anti-depressants or some such thing, without having to part with any money you do not have because payday is not until tomorrow. But people don’t fake lung cancer merely to get the sympathetic attention of a doctor. I mean, how would you even do that?

I was persuaded by two dear friends in particular that there was almost certainly something or other seriously wrong with me, and I was willing and could afford to reinforce my question with a stash of quite serious cash. I bought my way to the front of the diagnosis queue, and I do not apologise for this one little bit. I bought my way past various merely unhappy and somewhat discomforted people, and well done me. I now have a fighting chance. It turned out that I did indeed need serious medical attention and I needed it fast. My one big regret now is that I did not start waving my money around sooner.

As I say, it was the way that this original surmise of mine was so strongly confirmed by the experiences of others that made me sure that this was something worth me writing about, at the internet outlet I have at my disposal that will reach the greatest number of potential readers. What I’m saying is: Learn from me about how to throw money, in particular, at the diagnosis stage of a potential illness. If your problem proves to be no big problem and is easily corrected, well, fine, you’ve checked it out. Panic over. But if it is a serious problem, chances are you don’t want to be wasting time, and if you have the money, you should spend it and save the time.

Another way of explaining this is to point out that testing for things like cancer can get decidedly expensive, if it is to be done well. Soon after consulting my private sector diagnostic expert, I had about three different tests, each of them costing well over a thousand quid each. It makes no sense to give tests like that to people who are merely unhappy with their lives and their lot in life, and are telling you they have a tummy ache merely to get a little bit of your attention.

Or to put it yet another way, I look forward fondly to the time when such tests get much, much cheaper. Cancer care itself, I have been learning, is massively better than it was even a few short years ago. Well, likewise and one day, I’d like to think that instead of spending half an hour on some unwieldy and expensive space age contraption at the Marsden, there will come a time when all those complaining of bodily misfortunes, however slight, can just step through a gadget no more complicated than an airport metal detector. If the hit rate for serious conditions is a mere one per two hundred, or some such number, well that’s fine. Cheap at the price.

And don’t get me started on Brunel, which is the Marsden’s even space-agier device which has been giving me my first doses of actual treatment. Brunel is really something.

Like I say, my treatment looks like it’s state-of-the-art.

If this blog post saves or merely prolongs just one life, then good. Mission more than accomplished. This has not been that important a posting, and I certainly claim no originality for it. I’m sure many others have noted the same things as I have just been noticing. But, maybe for just one reader or friend-of-a-reader, it just might be the straw, so to speak, that saves one human camel’s back, if you get my drift.

This posting has been written in some haste, hence its rather excessive length. Brevity tends to take longer, I find. Also, I dare say there’s the odd typo or two, which I will correct as and when I or anyone else spots them. But I am sure you understand my haste. I have lots more things I want to say here before I make my exit, and it looks now like I have far less time to waste than I had earlier been supposing.

Is the challenge from YT Vlogger ‘bald and bankrupt‘, in this video, filmed recently in Cuba. ‘bald’ as he is referred to, appears to be a chap from Brighton (if you watch his oeuvre) who walks around various parts of our Earth and makes short documentaries about what he sees. He speaks fluent Russian (it seems to me, and his former wife we have been told is Belarusian) but not such good Spanish, and his sidekick is a Belarusian woman who does speak enough Spanish to get by and who interprets for him.

He presents Cuba by the simple device of walking around and going into several retail outlets to show what is on offer, and it looks pretty grim. He also talks to locals, most of whom seem well-drilled in what to say about the Revolution and to profess their loyalty to Fidel. He notes that everyone seems to want to escape. There is an unresolved side-issue of an abandoned kitten in the video.

And yet 10,000,000 people in the UK voted last December for a party just itching to get us to this economic state, without the sunshine. And in the USA, there seems to be far too much enthusiasm for socialism.

Bald’s ‘back catalogue’ contains a great travelogue for much of the former USSR. Whilst he admires all things ‘Soviet’ in terms of architecture (there is a running ‘gag’ about his excitement at finding himself in a Soviet-era bus station, he does acknowledge the grim reality of Soviet rule.

It’s now that time of the year between Christmas and the New Year, when we here sometimes do big postings with lots of photos. Usually, these have been retrospective looks back at the year nearly concluded. I did photo-postings like this in 2013, in 2015, and in 2017. And see also other such photo-postings here in the past, like this one in 2014, and this one way back in 2006.

We’re not the only ones doing these retro-postings about the nearly-gone year. A few days back an email incame from David Thompson, flagging up the posting he did summarising his 2019, which will already have been much read on account of Instapundit already having linked to it. And one of Thompson’s commenters mentioned a similar posting by Christopher Snowdon, mostly about politicians wanting to tell us what not to eat, drink or smoke.

So, here’s another 2019 retrospective. But it’s not a look back at the whole of 2019, merely a look back at a walk I took in London, on Christmas Day 2019. I like to photo-walk in London on Christmas Day, especially if the weather is as great as it was that Day.

I began my walk by going to Victoria Street and turning right, towards Westminster Abbey, where I did what I often do around Westminster Abbey. I photoed my fellow digital photographers, who were photoing Westminster Abbey:

The lady on the left as we look is using one of those small but dedicated digital cameras, of the sort that nobody buys now and hardly anyone even uses now, because the logical thing, unless you want something like 25x zoom like I do, or really great photos that you could blow up and hang in an art gallery, is to use a mobile phone. But she is still using her tiny camera from about a decade ago. Odd.

Next some giant purple Christmas tree balls, outside the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre.

→ Continue reading: Looking back at Christmas Day

Saturday’s Daily Mail carries this headline: ‘He’s a fraud’: Father of London Bridge terror victim Jack Merritt blasts Boris Johnson for making ‘political capital’ out of son’s death – and backs Jeremy Corbyn after TV debate

The article continues,

The father of a man killed in the London Bridge terror has slammed Boris Johnson for trying to ‘make political capital’ over his death.

David Merritt said the Prime Minister was a ‘fraud’ for using the attack as justification for a series of tougher criminal policies in a post on social media.

His son Jack Merritt, 25, was one of two people killed by convicted terrorist Usman Khan at a prisoner reform meeting in Fishmongers’ Hall last Friday.

What bitter irony that the two young people Usman Khan murdered believed strongly that criminals like him could change for the better. Because Jack Merritt and Saskia Jones were attending a conference on rehabilitation of offenders alongside Khan they were the nearest available targets for his knives. No doubt Khan planned it that way. One of the consistent aims of Islamists is to sow distrust for Muslims among non-Muslims.

David Merritt has suffered the cruellest blow imaginable. Nothing is more natural than that he should strive to counter the narrative that the ideals for which his son strove are disproved by the manner of his murder.

It is, of course, right to say that the ideal of rehabilitation is not disproved by one failure. No policy is proved or disproved by individual cases. Let us not forget that James Ford, one of the men who bravely fought to subdue Khan, was a convicted murderer on day-release.

However while Khan’s example of terrorist rehabilitation gone wrong does not prove that it can never go right, it is a data point. Thankfully we do not have many data points for the graph of jihadists playing a long game. But that means the ones we do have weigh comparatively heavily. What Khan did others can copy. The prime minister and those who make policy on parole and rehabilitation of prisoners must assess that possibility. They cannot allow what Jack Merritt would have wanted or what would ease David Merritt’s pain to factor in their decision.

In 2001 I wrote a pamphlet for the Libertarian Alliance called Rachel weeping for her children: understanding the reaction to the massacre at Dunblane (PDF, text). When discussing massacres carried out by Muslims with a Libertarian audience it is worth bringing up the subject of massacres carried out by gun owners, because our prejudices are likely to run in a different direction. We are better protected from the temptation to make group judgements. There are other common factors in how we should strive to think rationally about these two sorts of mass killing as well. In 2001 I wrote how the agony of the bereaved parents of those children preyed on my mind. I would have done anything to comfort them – except believe what I knew to be untrue.

When the parents of the Dunblane children spoke there was every reason for the world to hear about their terrible experience. There was never any particular reason to suppose that their opinions were right. In fact their opinions should carry less weight than almost anyone else’s should. This point is well understood when it comes to juries. It goes without saying, or, at least, it once did, that guilt or innocence must be decided by impartial people. Decisions of policy require the same cast of mind as decisions of guilt and innocence. The relatives of murder victims cannot be impartial. In a murder trial it is no use saying that it is as important to the family of the victim as to the judge that no innocent person be punished. In pure logic it ought to be, but in fact it almost never is. The bereaved want to believe that the evildoer has been punished. If the real evildoer has escaped (either escaped in the literal meaning of the word or escaped by suicide, as Hamilton did) someone must be found to suffer. Even in cases of pure accident we don’t have Acts of God any more: always some arm of government or business is pursued and sued so that the weight of blame may fall on somebody.

Following on from the posting below about the “ISIS bride” is this comment from Brendan O’Neill at Spiked:

Indeed, the story of these three London girls who ran off in 2015 was always a very telling one. It contains lessons, if only we are willing to see them. Too many observers have focused on the girls’ youthfulness and the idea that they were ‘groomed’ or ‘brainwashed’ by online jihadists. Note how ‘radicalisation’ has become an entirely passive phrase – these girls, and other Brits, were ‘radicalised’, we are always told, as if they are unwitting dupes who were mentally poisoned by sinister internet-users in Mosul or Raqqa. In truth, the three girls were resourceful and bright. All were grade-A students. They thought their actions through, they planned them meticulously, and they executed them well. Far from being the passive victims of online radicalisation, the girls themselves sought to convince other young women to run away to ISIS territory. The focus on the ‘grooming’ of Western European youths by evil ISIS masterminds overlooks a more terrible reality: that some Western European youths, Muslim ones, actively sought out the ISIS life.

A point that comes out of this is how it is so common these days to downplay the fact that people make choices and have agency. Whether it is about young adults joining Islamist death cults, or people becoming addicted to drink, porn or social media, or falling into some other self-destructive and anti-social behaviour, very often people talk about the persons concerned as passive, as victims. “She was groomed to be a terrorist”…..”he suffered from alcoholism”…..”he was damaged by over-use of social media”……the very way that journalists write sentences or broadcast their thoughts seem to suggest that people don’t really possess volition, aka free will. (Here is a good explanation of what free will is, at least in the sense that I think it is best formulated, by the late Nathaniel Branden.)

Sometimes debates about whether humans really do have volition can sound like hair-splitting, an obscure sort of issue far less important than other matters of the day. I disagree. For decades, centuries even, different arguments have been presented to show that humans are pushed around by whatever external or internal forces happen to be in play, whether it is the environment, toilet training, parental guidance, economics, the class system, whatever. Over time, these ideas percolate into wider society so that it becomes acceptable for people to talk as if their very thoughts and actions aren’t really under their control. The self-contradictory nature of people denying that they have volition (to deny is, after all, a decision) is rarely remarked upon.

When people think about the problem of “snowflake” students, or identity politics, or other such things, remember that these phenomena didn’t come out of nowhere. We are seeing the “cashing in”, as Ayn Rand put it almost half a century ago, of the idea that people are not agents with will, but mere puppets.

Update: A lively debate in the comments. There is some pushback on the idea that the ISIS bride sees herself as any sort of victim but I think that charge is correct because of the entitlement mentality she is displaying by demanding that she returns to the UK to have her child, and no doubt fall on the grace of the UK taxpayer. And that mindset is all of a piece of thinking that actions don’t bring consequences.

After all, if she is the devout believer in creating a Global Caliphate, based on killing and enslaving unbelievers and all the assorted mindfuckery of such a goal, it is a bit rich, really, for her to come back to a country the prosperity of which is based on it being a largely liberal, secular place. She wants to have her cake and eat it.

Of course, some young jihadis can be brainwashed and are surrounded by a culture that encourages such behaviour, but it is worth pointing out that there are hundreds of millions of Muslims who, whatever the pressures, don’t do these things, and some are trying their best to move away from this mindset. And one of the best ways that liberal (to use that word in its correct sense) societies can resist the pathology of Islamist death cults is by resisting the “victim culture” and insisting on people taking ownership of their actions, with all the consequences for good or ill that this brings.

As an aside, here is an interesting essay by a Canadian academic debunking what might be called “apocalyptic ethics” and a rebuttal of the argument that as religious fanatics embrace death, they are beyond the rational self interest test of ethics. The article deals with that argument beautifully.

It’s a little thing, but I always enjoy it when someone argues back, against what someone else has said, by replying: You’re wrong, because the reason why you’re right is …:

FACT CHECK: President Trump praised the record number of women in Congress, but that’s almost entirely because of Democrats, not Trump’s party.

Once you notice this, you notice it all the time.

“No Brian, you’re wrong, that doesn’t happen, because the reason that it keeps happening is because …”

Sure enough, it cropped up in my Facebook feed: “As usual, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is right: There should be no billionaires.” What does she say?

A system that allows billionaires to exist when there are parts of Alabama where people are still getting ringworm because they don’t have access to public health is wrong.

I came here to write about it, but Jonathan got here first. And he is right that classical liberal ideas are not popular. But I am optimistic that this can be changed.

I explained on Facebook that I thought Ocasio-Cortez is wrong for two reasons: Wealth is created. There’s not a fixed quantity of it. So billionaires don’t take anything away from anyone. Even just stating it like that is worth doing. Because deep down, people know it is true. They know that people do useful things or make useful things when they do work. Once you get past semantic misunderstandings about what “wealth” is, it is self-evident.

Even my second reason did not meet much objection: that the “system” that allows billionaires to exist is also the best there is. There is no other way of distributing resources without removing incentives from people. If people cannot keep the fruits of their labour, you get less labour in the world, and people on the whole will be poorer. It is not a hard point to understand. The example with the butcher and the baker works. There are plenty of examples of places with different “systems” and even more poor people.

I encountered the argument that no-one needs all that money and that billionaires are greedy. This is an opportunity to discuss how billionaires become so rich. The popular image of Scrooge McDuck and his pile of gold does not bear much scrutiny. Typically, billionaires are rich because they are useful in small ways to vast numbers of people. Businesses like Amazon, Paypal and Windows are very scalable. Bezos, Musk and Gates do not wake up thinking, “5 billion is not enough, where can I get my next billion?” They simply keep doing what they do because they enjoy it and they know how to do it.

Another objection I encountered is that nobody needs all that money. I think people have an image of a pile of gold being kept from poor people but it is not hard to pierce that misconception. There is only so much stuff a person can have. Billionaires do not have much more stuff than an ordinary, moderately rich person. Once you have a nice house, a boat, and a fancy car (which in any case has no more utility than a cheap family car), there is not so much more a person can have. What happens to the rest of the money? It is spent paying people to do things that are ultimately useful to other people. It is invested. Billionaires tend to be quite philanthropic, and they tend to have their own pet projects related to making the world a better place. Because there is very little else to do with so many resources. It is not hard to turn it into a discussion about whether Gates, Musk and Bezos are more likely to know how to improve the world than, say, the US Federal government. And it is hard to have an especially strong opinion that the US government knows best how to improve the lives of poor people. There is at least room for doubt.

And so ordinary voters, even ones who have suffered good educations, can be persuaded that billionaires are not a problem, and perhaps also that capitalism is not a problem, and perhaps also that redistribution of wealth is not the best way to improve the world. We need to develop the marketing techniques to do this, and then sell these marketing techniques to politicians. The left have claimed a monopoly on virtue for too long. It should not be so hard for classical liberals to dispense with the greedy banker image and market themselves as the ones who care about the poor and downtrodden enough to have solutions that work.

Yes, a rather belated Merry Christmas to all my fellow Samizdatistas, and similar wishes and thanks to all who read us and comment on us and on each other.

I’ve been trawling through my photo-archives for Christmas-related imagery, and here are half a dozen photos that I liked, and which I hope you will like also.

I photoed these people, many of whom were seasonally attired, in December 2012, as they disported themselves down by the riverside here in London, at low tide:

Next up, something topical, which Maplins in Tottenham Court Road was trying to sell as a Christmas present in December 2014:

Sadly, Maplins is now bust, and Tottenham Court Road’s electrical business is now in steady retreat, in the face of advances by clothes and furniture stores.

Next, taken exactly two years to the day after that drone photo, some literature. In Foyles, under the Royal Festival Hall:

Next up, a typically discontented crop of Newapapers, again, December 2016:

And finally, a couple of snaps taken in January of this year, in Lower Marsh, which is one of my favourite London haunts, or it was, until Gramex closed its doors. Sign that you’re getting old: your favourite shops keep closing. Lower Marsh is the kind of place where the effort they put into their Christmas windows tends to linger on into mid-January.

First of these last two, a selfie in a shop window, a favourite photo-genre of mine, featuring some satisfyingly ancient technology in the foreground:

I never could be doing with photography until the digital version of it arrived just before this century did, but I still use a phone like that one.

Finally, this, taken minutes later:

I don’t know what that creature is. His expression suggests that something just went wrong with his Christmas cooking.

Here’s hoping nothing goes wrong with your Christmas or with your Christmas cooking, or for that matter with mine.

It appears that Kenya has some something surprisingly sane: it has decided to remove portraits of real people, especially politicians, from its currency.

At one time, policy in the United States was quite similar; anthropomorphic representations of abstract concepts (like “liberty”) were the only human images permitted on government produced money. Then, slowly, the inevitable happened, and politicians began to be deified by putting the likes of Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Jackson, and the rest on coins and bills.

I think the notion that senior politicians are not, in fact, kings and emperors, and ought not be the subject of secular worship, remembered with expensive public memorials, put onto money, have bridges and airports named after them, etc., is a rational one, and I hope that it someday becomes much more widespread.

Tomorrow is the U.S.’s Thanksgiving holiday. It is a fine time to reflect on the bounty that the productivity increases brought by capital accumulation and technological improvements have brought to us.

The cost of the ingredients of a Thanksgiving feast for ten are now said to cost an average worker their wages for under 2.25 hours of labor. A 16 pound turkey now costs less than what an average worker earns in an hour.

We live lives of such astonishing wealth that we scarcely notice it. Only a fool would rather be an Emperor in 1600 than a poor person living today. Compared to a king of several centuries ago, poor people in the developed world live in astonishing luxury. In the developed world, we eat fresh vegetables in midwinter, our homes are heated toasty warm in the winter and cooled and dehumidified in the summer, we travel in enormous comfort (no wooden wheeled carriages without shock absorbers for us, and indeed, we can fly to the other side of the world for a quite modest sum of money), our medical care is incomparably better, our beds more comfortable, our entertainment options beyond any ancient potentate’s wildest dreams. This is true even of quite poor people, at least in developed countries.

Whence comes this bounty? It is not because of union organizing, or minimum wage laws, or the triumph of the proletariat over the evil factory owners. Indeed, a few centuries ago, there were few mass production factories to triumph over.

No, the source of this bounty is productivity, and the engines of productivity are deferred consumption being invested in improved infrastructure (that is, capital accumulation), improved technology, and specialization. Thanks to our better means of making things and the sacrifices needed to construct those means, productivity per worker is orders of magnitude higher, and thus there’s more stuff to go around.

Centuries ago, it required something like 750 hours of human labor to produce a simple tunic; today it requires minutes of human labor. Almost no one is capable of truly internalizing this change. The shirt on your back once was a valuable capital good requiring four months of constant labor to produce. Now it’s not even worth repairing if it tears, it’s too inexpensive to replace it. Because of this change in productivity, even quite poor people in developed countries own many sets of clothing.

Centuries ago, there was barely enough food to go around, and often far too little, as a result of which starvation was common. It required constant labor by most of the population to produce enough food. Then, mechanization of agriculture set in, and the production of synthetic fertilizer, and pest control, and improved breeding methods; today, it requires very few people to grow more than enough food for everyone. There is so much food, in fact, that obesity has become a disease of the poor, an unprecedented development in human history.

So it is across the span of consumer goods. The amount of labor it requires to produce enough light to read at night has gone down by orders of magnitude, and the quantity of light produced by an ordinary lightbulb is 100 times greater than that of a candle at a tiny fraction of the price. Many goods didn’t even exist before; in my father’s youth there were no televisions, and now people can buy 4k 130cm flat screens.

We were assured by Marx in his writings that the unavoidable result of capitalism over the long term would be the persistent reduction in the quality of the lives of poor people. This was inevitable because capitalists would be forced to engage in greater and greater extraction of the surplus value of the production of their workers. As with essentially all of Marx’s predictions, this did not come to pass; indeed, the opposite has been true.

Marx’s views were based in an entirely counterfactual set of theories of how the world works. Sadly, even though essentially everything Marx claimed about economies and society has proven false, and although essentially every prediction he made has been falsified, and even though his ideas led to the deaths of at least 100 million people in the 20th century, Marx is still wildly popular with the supposed educated classes of our society. (Indeed, even though Marx’s vicious bigotries were the cause of as much or more horror than those of the fascists, it is still respectable for academics to call themselves Marxists. Calling yourself a Nazi will rightfully cause you to be ejected from polite society, but call yourself a Marxist and you can get tenure. But I digress.)

Sadly, the myriad of capitalists that have kept us fed, warmed, clothed, entertained, and healed are largely forgotten. Like fish forgetting they live in water, we forget most of the time that we owe so much to the market economy we are surrounded by, to the vast number and diversity of producers, bringing to bear astonishing specialization and division of labor, creating an incomprehensible number of goods.

We owe so much to people in the past denying their current wants to carefully invest in the future that they might have more tomorrow. It has been the capital they slowly accumulated for us over centuries that has made us all so comfortable. The resources carefully husbanded by capitalists looking to the future were converted into capital equipment of all sorts, from house insulation to computer networks, from injection molding machines to automated teller machines, from to MRI scanners to torque wrenches.

Ultimately, we owe everything to them, and to the never-ending quest for higher productivity among selfish people desperately trying to out-compete their brethren. To quote Adam Smith:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

So tomorrow, when I, as with millions of others sit down to have an unnecessarily large meal with my family, I’ll try to be mindful of how hard the struggle was to move from caves and huts to comfortable modern homes, from bare subsistence to feasts that can acquired by trading less labor than it used to require to make a chair leg, from a world lit and heated only by fire to one where I can sit in shirtsleeves reading comfortably at night while a freezing wind howls outside.

What’s even more amazing is this: if people cease to try to prevent the world from getting better, our descendants may pity those living today for our astonishing poverty, for they may someday be vastly richer than we are.

Today is the 100th anniversary of the armistice that ended World War I, which killed something between 15 and 19 million people, an astonishing and colossal waste of human life and potential.

Sometimes it is necessary to engage in violence to prevent even worse violence, but it is always a terrible thing when that happens, and is nothing to be celebrated. At best, the “victory” of the allies was that nothing particularly worse happened, although what happened (including the deaths of about 2% of the population of Great Britain and 4.25% of the population of France) was pretty much as awful as one would imagine to begin with. As an anti-nationalist, I note that there is no good reason to believe the deaths of millions of Austrians and Germans (something like 4% of the population in those countries) was any less of a tragedy. All deaths are tragedies, and all deaths are premature.

War is not glorious. It achieves no great goals. It cures no diseases, it bridges no rivers, it builds no great cities, it does not launch people into space, clothe the naked, or feed the hungry. Those are worth celebrating, those sorts of achievements represent mankind at its best. War does quite the opposite thing — it destroys resources in bulk, kills vast numbers of people, and sets back human achievement, sometimes by years, sometimes by decades or longer.

Nor is participation in war laudable. Sometimes it is necessary to defend oneself, but there is never any glory in it. Dying face down in the mud is tragic, not glorious, and World War I was almost nothing but one tragedy after another, over and over, multiplied by the millions.

So, today is properly a day of mourning, for a world that was happily growing in population, accumulating capital, and engaging in peaceful trade, which was rent asunder by a stupid, useless waste of human life.

At one point, this trauma was deeply etched into the minds of most average people, but the memory has faded as the generations have passed, and thus the world flirts with horror again and again. Humans do learn, but far too slowly, and there are many people who work actively to tell other people things that are not true.

Sadly, intelligence and rationality are not universally revered, and thus, many are forced to learn the same things over and over, with bloody results.

A week or so ago I went to see The First Man at the cinema. At first it seemed to do a good job of turning historical figures into real people. The domestic lives of the astronauts contrasted with the bravery of their test flights. There were lots of scenes of worried housewives which seemed believable enough. Armstrong is portrayed as a serious engineer with good attention to detail. He makes some mistakes which his bosses put down to being distracted by his daughter’s ill health. After she dies, Armstrong is understandably never truly happy. He does not express his emotions, and tells one friend who tries to talk to him, “if I wanted to talk to someone, do you think I would be standing out here [away from everyone]?” I like that line: I have felt like that at times.

When the Gemini 8 flight has problems, his wife hears about it and she goes to complain that her audio feed has been switched off to protect her from hearing about what is going on. Don’t worry, she is told, we have everything under control. No you don’t, she retorts, “you’re a bunch of boys playing with balsa wood models.” There is a certain truth to that line which I enjoyed: it is hard to have complete understanding of a complex enough system, and there is a certain playfulness to engineering.

There is a montage about protestors complaining about the cost of the Apollo program and listing better ways of spending tax dollars such as by helping poor people. We see Gil Scott-Heron on stage reading his poem Whitey On The Moon. It made sense to portray these things in the movie.

A lot of Armstrong’s colleagues are killed. The Apollo 1 cockpit testing scene is hard to watch if you know what is coming. A lot of the movie is spent with Armstrong taking the deaths hard. There are a lot of funeral scenes. There is a scene where Armstrong’s wife makes him explain to his kids that he might not survive Apollo 13.

They fly to the moon. I have a big criticism of the cinematography: I am sure spacecraft do not vibrate that much. There must be other ways to portray speed and acceleration. They fly home. Once home, Armstrong’s wife visits him in quarantine. He seems sullen. She seems sullen. The End.

And then it hit me: no-one is happy about going to the moon. There is no pride, no sense of achievement, no celebration of the accomplishment whatever. All we learn is that we are doing it to beat the Soviets, it costs a lot of money, there is a huge human cost, people worry and suffer, relationships are strained. This is a joyless movie. It portrays no up-side. The closest we get to any kind of positive commentary on the Apollo project is when Armstrong first applies for the job. The superiors ask why he wants to go to the moon and he answers with a speech about mankind’s need to explore. The superiors seem skeptical, but pleased: the message is that this guy can be trusted to say the right things. Being happy about going to the moon is for the stupid masses.

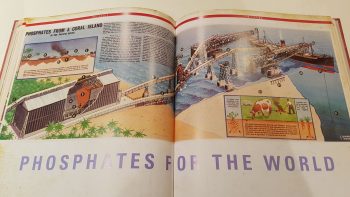

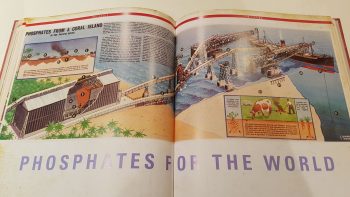

On my bookshelf I have a couple of anthologies of the Eagle comic from the 50s and 60s.

Phosphates for The World They feature cutaway drawings explaining wonders of technology, present and future, all of it wonderfully unapologetic. We are doing awesome things and we will do even more awesome things soon, kids are told. Today’s teenagers are bombarded with worry and pessimism. BBC Focus magazine is a science magazine that seems to be aimed at young audience and it features an article about climate change and how having children is bad. The Week Junior seems to be full of articles about endangered animals and banning plastic. If I did not know that most of the terrible problems are not terrible problems and that the world is in general getting better, I might be a bit despondent about all that. If I was an impressionable youth I might rebel against it; I hope they do.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|