We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

My friend Bernie emailed me with the link to this short Radio Times film review of The Godfather, shown last night on Channel 5. Spot the anti-capitalist bit.

This crime drama and its 1974 sequel are among American cinema’s finest achievements since the Second World War.

The production problems are well documented — how Paramount wanted a quickie, how Francis Ford Coppola came cheap and how he turned the picture into an epic success, a box-office hit that was also an artistic triumph.

His first masterstroke was casting Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, James Caan, Robert Duvall and Diane Keaton, four relative unknowns and one known risk; his next masterstroke was to keep cool under fire, like Michael Corleone himself, turning Mario Puzo’s pulp novel into art and showing how capitalism and crime go hand in hand.

It’s thrilling, romantic, tense and scary – a five-course meal that leaves you hungry for more.

“… capitalism and crime go hand in hand.” Another of those implied solutions that dare not spell itself out clearly. Wanna get rid of crime? Rub out capitalism. But if thus challenged, the anti-capitalist replies: “but I never said that”. If unchallenged (which is how most readers will get the message), he did say it.

This is why we need our own publications, to edit out sneaky little innuendoes like that, and to insert our own.

It would be truer to say that the legal creation of victimless crimes goes hand in hand with crime, and that the state (a) claiming a universal monopoly in the supply of law and order but then (b) not supplying it anything like universallly goes hand in hand with crime.

Will this get a link from Biased BBC?

One of the great pleasures and advantages of living in Pimlico, in central London, is its proximity to one of the world’s great art galleries, The Tate, a fine classical building looking over the Thames. Recently my girlfriend and I went around two separate exhibitions and had two contrasting experiences not far different in extremes from the North Pole and the Sahara Desert.

The first exhibition was a display of Pre-Raphaelite art, from that group of talented, romantic and at times eccentric group of artists in the middle of 19th Century England. They took their inspiration, as the word pre-Raphaelite suggests, from the Renaissance artist Raphael. Some of them were intensely religious, while others took a passionate interest in the natural world.

I must say I have mixed reactions to their art. Some of the paintings, particularly the coastal seascapes and the depictions of the Swiss Alps, were stunning. Others, while rendered with incredible attention to detail, left me rather cold. There is something almost rather mannered about this art, as if it was produced by someone trying too hard to impress. On the whole, however, I could not fail to be struck by the descriptive lust of these artists, their desire to convey the world as they saw it and as it could be.

And then, after a slurp of wine – we were at a private viewing – we set off to another part of the Tate for an altogether different experience, namely, a selection of ‘art’ (I will explain the inverted commas a bit later) by some of the world’s newest artists, including the so-called enfant terrible of the Brtitish art establishment, Damien Hirst., and Sarah Lucas, about whom I had not heard before.

Some of the exhibits featured dead animals inside tanks containing fluids, bits of sausages, live fish, a brain, bottles of wine, a bucket, and other bits and pieces I could not readily identify. Two exhibits were models of people undergoing surgery, with nothing showing apart from their genitals. Several large oval-shaped boards were covered with hundreds of dead butterflies. An empty full-size truck cab, plastered in its interior with tabloid newspapers, had a man’s arm pumping up and down in a familiar sexual act. In fact, several exhibits seemed to portray human bodily functions, as if the exhibits had been assembled by a sniggering, slightly conceited 12-year schoolboy trying to shock his elders.

I will not deny Hirst and others like him are folk with a certain talent. They are talented in much the same way that pickpockets can be said to be talented. But to what effect? So much of his art seems to shout, “I am taking the mickey out of you stupid, repressed middle class wankers”……No doubt Hirst thinks he is being ever so clever and subversive, and judging by the large audiences for his work, he probably is. What perhaps is forgotten is that the image of the artist as the mocker of bourgeois sensibilities, far from being daring and new, is in fact very dated, and bang in line with the ethos of the Modern Art establishment. They are the bores of our age.

There you have it. About 150 years from the Pre-Raphaelites, we have gone from the ability to portray nature with passionate concern for accuracy, and an essentially warm embrace of human life, to lumps of meat in tanks, and to images of human beings sitting on the toilet, smoking a cigarette. Perhaps these folk really have caught the meaning of Blair’s Britain, after all.

Addendum: if you are as disgusted as I am by the bogus nature of much modern art, but cannot always put that disgust into words, then I strongly recommend the book, What Art Is, written by Louis Torres and Michelle Marder Kamhi. It unashamedly defends representational art, questions whether certain forms, such as abstract painting, really can pass muster as art, and perhaps controversially, argues that photography does not pass the test. I do not agree with everything in the book but it is well worth the attention.

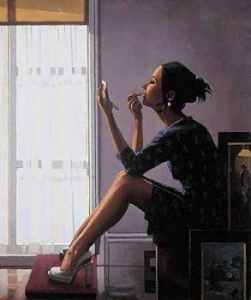

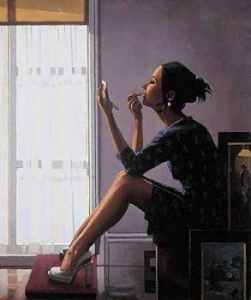

Jack Vettriano may sound like a Sicilian mobster but, in fact, he is this country’s most popular and successful artist.

Born in Scotland, he started out his working life as a mining engineer before a girlfriend bought him a set of watercolour paints for twenty-first birthday. He taught himself to paint and embarked upon a career as an artist. Today, reproductions and prints of his work massively outsell those of Monet and Van Goch and originals hang in the collections of the wealthy and famous (making Vettriano pretty wealthy and famous himself).

Only the Deepest Red Vettriano’s deeply evokative work is rich in art deco erotica noir: elegant, sexy and (in this day and age) subversive. While many artists use a canvas to tell a story, Vettriano uses his to write a seductive novel full of unambigiously masculine and feminine characters. → Continue reading: He’s alright, Jack

Yesterday evening I was channel hopping by way of relaxation and chanced upon a UKTV History programme about the Cold War, and in particular about the doings and sayings of the rocket scientists. (Here is the UKTV History home page, but I can find no internet reference to this particular programme.)

The programme seemed fairly good, on the whole, but towards the end of it there was one glaring – not to say outrageous – non sequitur. → Continue reading: The UKTV History channel – underestimating Ronald Reagan and his rocket men

Trafalgar Square is located at the geographical centre of London and, next to ‘Big Ben’ and the Houses of Parliament, it is probably this country’s most famous landmark.

Named after the 1805 battle, the Square is dominated by a 200 foot column on top of which is perched a bust of the Horatio Nelson, the Admiral who let the Royal Navy to victory over the French and thereby saved Britain from Napoleonic invasion. The column that bears his name and image was built from donations offered up in tribute by a grateful nation.

In the four corners of the Square there are four plinths. Three of them are occupied by statues of King George IV, General Charles Napier and Major General Sir Henry Havelock. The fourth plinth is empty and has been since around the middle of the 19th Century.

A few years ago I became vaguely aware that there was something of a campaign to find an appropriate monument to place on the fourth plinth. I say ‘vaguely’ because I paid little attention to this campaign, partly because I have better things to do with my time and partly because I learned that the process was to be decided by means of a competition under the auspices of the Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone. I anticipated that I would most likely disapprove of the outcome.

My instincts proved trustworthy yet again for, this last week, the winner was unveiled.

As you may already have guessed from the image, Ms. Lapper has never led anyone into battle nor has she ruled a kingdom. Instead, she has managed to bear a child despite being quite severely disabled. → Continue reading: We are the masters now

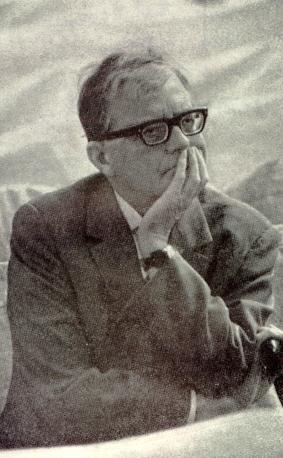

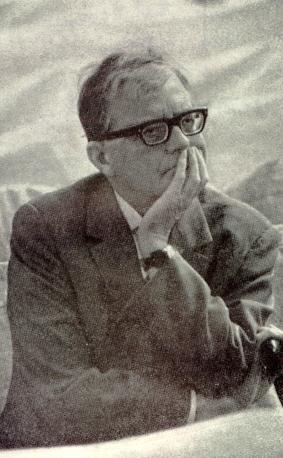

I was and am a devout anti-Communist. I rejoice that civilisation won the Cold War, detest the evil folly that was Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism-decrepitudism, and regret that the Russian Revolution was not strangled at birth. But (and you could hear that coming couldn’t you?) as far as I am concerned, Dimitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) was almost certainly a better composer after Stalin had given him his philistine going-over following the first performances of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, than he would have been if Stalin had left him alone. Although both are very fine, I prefer Symphony Number 5 (“A Soviet Artist’s Reply to Just Criticism”) to Symphony Number 4.

Had Shostakovich continued unmolested along the musical path he was travelling before Stalin’s denunciation of him, I don’t think he would merely have become just another boring sub-Schoenbergian modernist. He was too interesting a composer for that already. But I do not think his subsequent music would have stirred the heart in the way his actual subsequent music actually does stir mine, and I do not think I am the only one who feels this way. → Continue reading: Dimitri Shostakovich was a very nervous man

Samizdata’s commentariat sometimes irritates, but I generally find that when I ask it a technical or factual question, then in among the waffle I get good and pertinent answers, and now I have another question, concerning copyright. It was provoked by a phone conversation between me and Findlay Dunachie (who is a real person and who does live in Glasgow) about culture (harking back to my posting about that talk I am to give), by which we both meant music, pictures, etc. (rather than the incoming tide of brown people that threatens to bring all of civilisation to a standstill). I said I was interested in … whatever it was, and Findlay replied that, on the other hand, one of the cultural things that particularly interested him was why, although we can all now own cheap CDs of great symphonies and concertos and operas and oratorios, we cannot drop into a museum and view full size, electronic reproductions of all the world’s great artistic masterpieces. Why cannot museums get that organised? Is it original object fetishism? Are we only staring at vast sums of money when we look at paintings, so would copies not count?

I do not know anything like all the reasons why this cannot or does not happen. But here are some guesses.

Good copies of great paintings are technically quite hard to contrive, especially at full size. There is a comment about that from Alan Little on this Brian’s Culture Blog posting, which was about colour variations between different electronic versions of the same painting on the internet, and about the closely related matter of colour variations between different computer screens.

Also, there does seem to be a difference between, say, my willingness to pay £5 or even £10 for an old recording, and my utter unwillingness to pay as little as 5p for an electronic copy of the Mona Lisa to stare at on my cheap computer screen. Maybe there are actually plenty of fabulously good copies out there, but at a price, and I am a cheapskate. And maybe I am not the only one. But even if all that is true, you would think that museums could do deals amongst themselves to get around all that. So maybe us punters do only want to see the originals, no matter how great the potential copies.

But, and this is where I have a specific question to which I seek a specific answer, I rather think that there is another inhibition at work here. Pictures stay in copyright for ever, unlike sound recordings.

It is perfectly possible for a business like Naxos Historical to flourish, and it does, no matter how much its very existence may enrage the great recording enterprises whose recordings it (perfectly legally) makes use of, after the passing of only a few decades (my understanding being three, but maybe the Europeans will change/are changing/have changed that to five). But no matter how many decades elapse, with pictures it is different. With recordings, after a few decades, all bets about the legality of copying are off. With paintings, no matter how long ago – how many centuries ago – they were painted, all those bets remain on. And it is the same with imagery of any kind, that is to say with photographs (which are a more exact equivalent of sound recordings than paintings are).

The central question to which I seek a definite answer is, simply: is that right? I have been running my Culture Blog now for well over a year, and I am rather ashamed that I still do not even approximately know the answer to this question about the legality of image copying, but better late than never.

There is also the question of whether the legal facts of image copying ought to be the legal facts. Is what now happens right? In general, and assuming that I am very roughly right about this, what on earth is the justification for treating imagery so extremely differently from sound recordings? I am sure that there are good reasons for this sharp difference, but I have never thought about what they might be, and it is time I did.

My thanks in advance to any commenters.

In just over a week’s time I am to give a talk in Brussels, courtesy of the Centre for the New Europe, on the subject of Why Libertarians Don’t Talk About Culture – And Why They Should.

When you are extremely grand, you let things like this come and go with no comment from you other than the occasional “oh yes, that, yes, I think it’s on the fifteenth, I’m not sure” (it is on the fifteenth), or “oh that, yes, I’d forgotten all about it”. But if you are me, you make the most of these sort of invites. If I don’t tell everyone I am doing this talk, who else will?

Here is the blurb I sent to my hosts about it:

Libertarians don’t believe in either subsidising or censoring cultural activity, so for libertarians it often doesn’t matter what they personally think about any particular cultural object or enterprise. Good or bad, it should neither be encouraged nor prohibited by the political process. So long as you don’t infringe against the rights of others, you can enjoy “culture” any way you like, or in no way at all.

For collectivists on the other hand, the goodness or badness of a particular cultural enterprise is a burning issue, because the collective must decide what sort of culture to encourage or discourage. So, they talk about culture a lot.

The result is that libertarians often appear philistine, shallow and one-dimensional, while collectivists can seem far more cultured and attractive. So, we libertarians ignore culture at our peril.

I have already ruminated on this topic here, in this posting, and the blurb above owes much to those ruminations.

Maybe another reason why libertarians are a little reluctant to talk about culture is that we fear that quarrels about inessentials, like how good the Lord of the Rings really is, are liable to undermine team spirit amongst us to no purpose. That is a mistake, I think, but maybe some libertarians feel that.

I think that the claim in part one of my talk’s title, that libertarians do not talk about culture, may now be becoming obsolete. With the Internet, blogging etc., we libertarians now have a means of chatting away about movies and literature and stuff, in a very congenial and magazine-like setting, yet without all the bother of anyone having to put together an actual magazine – which is a total nightmare compared to running a blog. The reason we used not to talk about culture was simply that it was too difficult. It was all we could manage to bang away with our core agenda. Now, simply, we can do culture talk, and we do.

Well, those are my thoughts so far. Does anyone here have anything else to say about all this? I would really welcome the input.

UPDATE: This very recent comment on this posting might have something to do with why libertarians don’t discuss cultural themes. When they do, they get denounced by people saying things like this:

What does this have to do with libertarianism? I come to this blog to read libertarian views and issues, not artistic commentary.

This, to me, is a perfect example of a libertarian (if that is what Telemachus is) being boring and philistine.

Last night I actually went out, to a cinema, to see a film, with some friends. No pause button, no stopping if bored, no incoming phone calls, no life at all, except watching and listening to and thinking about the film. And then after that, sparkling conversation, in a restaurant. Very peculiar. Very delightful.

The film was The Barbarian Invasions, which was the movie that got the Best Foreign Film Oscar (just as Michael Jennings hoped it would) on account of Lord of the Rings Part 3 (and I seem to recall someone thanking Lord of the Rings 3 for this on Oscar night itself) not having been a foreign film.

Preliminary googling while I gathered my thoughts about this movie got me to this review of the movie by Peter Bradshaw in the Guardian back in February, which is one of the most fatuously wrong-headeed pieces of writing I have ever had the good fortune to read and laugh out loud in amazement at. Bradshaw gets hold of the stick all right, but at totally the wrong end.

The story concerns a bunch of reunited lefties left over from an earlier film, which I haven’t seen, one of who is a certain Rémy, who is now … well, let Bradshaw tell it:

Rémy is now grown into his 50s and hospitalised with a fatal tumour in his home town of Montréal, insisting on state care and railing against the barbarians of philistinism and extremism destroying the world. His wealthy merchant banker son Sébastien (Stéphane Rousseau), described by Rémy as a “puritan capitalist” in contradistinction to his own “socialist hedonism”, is still angry with him for breaking up the family home but is nevertheless prevailed upon to return to his bedside, and the slow process of reconciliation begins; Sébastien gets on his mobile to reassemble all Rémy’s old friends and lovers.

So far so good. Nothing wrong with that. That is what happens. But now Bradshaw careers ludicrously off the rails: → Continue reading: The Barbarian Invasions – the future belongs to me (but not to Peter Bradshaw of the Guardian)

Well, it’s Oscar night this evening. The big question seems to be whether Mel Gibson will make an appearance as a presenter, and if so what he will say and what the reaction will be. (If his aim of releasing The Passion of the Christ was simply to make a lot of money, he has succeeded. The film has grossed $118m in five days and as Gibson put up the entire budget himself, almost all of the profits will go to him). However, as I promised I might when I wrote my overlong overview of what happened in the Holiday and New Year film season a couple of weeks ago, here are my predictions as to who are going to win the Academy Awards this evening. Some people might think that the Oscars are too trivial for a Samizdata post, but if you think this, don’t read. If it is good enough for Mark Steyn, it’s good enough for me. (How do I begin my campaign to be the next Spectator film critic).

I have of course refrained from using the special hotline that we Samizdatistas have direct to the Stonecutter World Council to find out in advance who the winners are, so I am just guessing using my judgement here. I will stick to the major categories, with perhaps occasional thoughts on the other categories.

As well as merely trying to predict the winners, as an added bonus, I give you a star ranking. Four stars means I will eat my metaphorical hat if this is not the winner. Three stars means I will be quite surprised if this is not the winner. Two stars means that I think this will be the winner, but that I think that there are other possibilities that would not be an overwhelming surprise. One star means that the category looks very open and I have no idea, but that I am willing to guess. I will give other people I think who are in with some kind of chance in brackets, and if I list more than one such person I list most likely first. I may or may not follow this up with a sentence or two as to why but I will try to keep it brief. In a couple of instances I will elaborate on my reasoning at more length on the special blog I use for that purpose, and will link to those comments.

Anyway, here goes.

The full nomination list is here. → Continue reading: Yes, it’s Oscar Night.

Sticking with the religious theme, I am puzzled by the furore regarding Mel Gibson’s acclaimed flick, The Passion of The Christ

An American Jewish leader met with Vatican officials to ask them to publicly restate church teachings on Jesus’ crucifixion. Anti-Defamation League Chair Abraham Foxman says that Mel Gibson’s film “The Passion of the Christ” contradicts the Vatican’s repudiation of the charge that the Jews killed Jesus. A top Vatican official who met with Foxman said no such statement is planned. Archbishop John Foley, who heads the Vatican’s social-communications office, instead praised the film and said he found nothing anti-Semitic in it.

The way I see it, a couple thousand years ago a Jewish man called Jesus, most of whose followers were Jews, was executed on the basis of trumped up charges. This was done with the grudging sufferance of the Imperial Roman authorities at the behest of certain powerful Jewish political and community leaders. Thus it would be fair to say he was killed by Jews.

This is of course not at all the same thing as saying he was killed by the Jews: that makes about as much sense as saying “John F. Kennedy was assassinated by the Caucasians”.

This is just history, guys! What is the big deal?

I’m listening to an old nineteen thirties recording of some Dvorak symphonies. The conductor and orchestra are both greatly admired for this music, yet I find little pleasure in the experience. For me, symphonies, by their nature, only really work properly if the recording is decent, as the best recordings were from about 1960 onwards, but as these ones, made in the 1930s, are not.

Concertos are another matter. One of the greatest pleasures I’ve recently got from classical CD collecting is from the Naxos historical CD series. True, as with the symphonies, you don’t get the full orchestral picture clearly, but a solo instrument can still come across very clearly, despite the barrier of the decades. What classical music lover would deny himself the pleasure of hearing the teenage Yehudi Menuhin performing the magnificent Elgar Violin Concerto – recorded in 1932 with Sir Edward Elgar himself conducting – just because the recording quality is not quite up to modern standards? The orchestra is not all you’d like, but the solo violin is clear as a bell. → Continue reading: Reflections on the future of the musical past

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|