We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

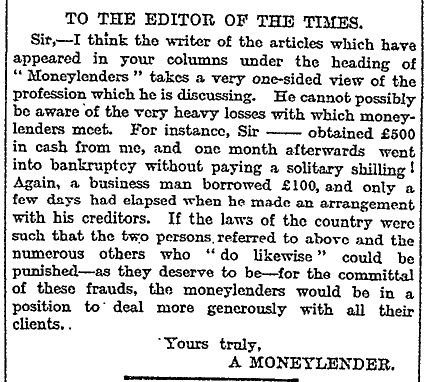

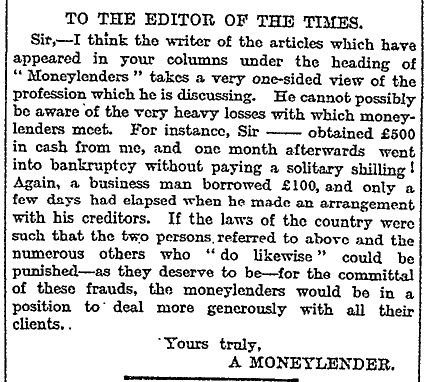

I see that the Church of England is about to go into the moneylending business. They appear to think that it is easy. If so, they might like to consider this moneylender’s words:

The Times, 11 July 1913 page 3. Or this one. (I liked the bit about even the Church having to lend out its money.)

The Liberty and Property Defence League also has a few things to say.

QE has had another effect which is rarely quantified. The Newedge study calculates that 47 per cent of all S&P 500 earnings growth since 2009 has been derived from the interest expense savings from declining interest rates, a large chunk of which has been created by the Fed’s interventions. A puncturing of the credit bubble would send the cost of borrowing shooting up, and thus reverse many of these gains.

We have had the tech bubble (partly driven by cheap credit); we had the property bubble (driven by cheap credit), we now see a bond bubble (ditto)…….

Read the whole article. The CityAM piece is not the first to broach the issue, but as an overview, it is very good indeed.

Admit it. You love cheap clothes. And you don’t care about child slave labour…

So sayth Gethin Chamberlain in The Observer.

Well… seeing as he puts it that way… I suppose it would be better if these Third World folks were unemployed (and thereby provide a lower carbon footprint of course, not to mention gainful employ for First World NGOs involved in the Pity & Guilt Industry) and depending for their survival on First World aid money, disbursed via their government. The important thing is that The Islington Set can feel good about increasing the price of clothes for the British lumpenproletariat… and just remember that a lot of those bastards with their false consciousness and lack of class awareness voted for Thatcher back-in-the-day!

Of course much the same was said about The Dark Satanic Mills of the industrial revolution. But just as in India, people moved into the ghastly factories of the Midlands and elsewhere because it was better than the subsistence of grinding rural poverty… and this ultimately led to the technological mass affluence of today that has taken the vast majority of humankind beyond one-failed-harvest-from-starvation.

This is the headline from today’s Daily Telegraph:

Training and employing British workers is more important than a firm generating profit, business minister Matthew Hancock has indicated.

In the article, the wretched individual goes on to state that his comments should not be seen in the same light as Gordon Brown’s infamous nonsense in favour of “British jobs for British workers”. Well, it certainly looks to anyone with a grasp of language that this man is stating that national origins should count for a lot in hiring, and goes to the extent of saying that choosing a Brit is more of a factor in hiring than whether that person will increase the prosperity of a firm, which is normally why people get hired in a free market.

Ah, I mentioned the term “free market”. Silly me.

Here is some background from his website:

Matthew John David Hancock grew up in Cheshire. He attended Farndon County Primary School, West Cheshire College and The King’s School, Chester. He studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at Exeter College, Oxford, and gained a Master’s Degree in Economics from the University of Cambridge.

So he read economics, and thinks he knows better than commercial organisations as to whom they should hire.

Matthew’s first job was with his family computer software business. Later, he worked for five years as an economist at the Bank of England and in 2005 moved to work for the then Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne.

Blow me down – the man had a stint in the private sector! But that did not last long and soon enough, he was working for the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street, which is now run by a Canadian governor, so presumably he disapproves of his government’s own decision to take a chance on hiring a foreigner.

This man represents a safe-ish seat in West Suffolk, which is near where I come from originally; he loves horse racing and in many ways I am sure he is a splendid chap, a bit of a Tory “knight of the shires”, as he hopes. But the thudding ignorance of his claim that firms should hire Britons first rather than take the “easy option” of hiring foreigners ignores the reasons why firms are doing this. I assume he realises that firms hire foreigners not just because of costs, but due to issues such as behaviour, character, work-ethic, and so on.

We should of course recall that the Tory party – as it used to be called – was the more protectionist force in the past – as demonstrated by the ruckus caused when Sir Robert Peel scrapped the Corn Laws in the 1840s, triggering a split in his party, and at the early part of the 20th, the attempt to re-impose tariffs caused a similar uproar. On immigration, the position has altered over the years: during Maggie’s time in office, and after, Tories were sometimes (unevenly) quite keen to stress how welcoming the UK is to certain people from overseas, not surprisingly perhaps given that several members of the Cabinet and parliamentary party were the descendants of immigrants (Nigel Lawson and Michael Portillo). It is a shame to see zero-sum thinking return to the party under the patrician, “nudging”, government-knows-best approach of David Cameron.

I hope businessmen give this minister a sharp kick in the shins. Better still, it would be no great loss to see his department closed down.

From the Wall Street Journal today:

A $91 billion industrial project here, mired in debt and unfulfilled promise, suggests part of the reason why China’s economy is wobbling – and why it will be hard to turn around. The steel mill at the heart of Caofeidian, which is outside the city of Tangshan, about 225 kilometers (140 miles) southeast of Beijing, is losing money. Nearby, an office park planned to be finished in 2010 is a mass of steel frames and unfinished buildings. Work on a residential complex was halted last Christmas, after workers completed the concrete frames. There is even a Bridge to Nowhere: a six-lane span abandoned after 10 support pylons were erected.

“You only need to look around to see how things are going,” said Zhao Jianjun, a worker at a plant that hasn’t produced its steel-reinforced plastic pipes for months. “Look north, west, east,” he said, gesturing to empty buildings. Chen Gong, chairman of Beijing Anbound Information, a Chinese think tank, says Caofeidian shows the flaws of the Chinese economic-growth model, in which the government plans investment and companies are expected to follow suit, regardless of market conditions. Chinese local governments are “driven by the blind pursuit of GDP,” said Mr. Chen.

There are reasons why I have doubted much of this “China will overtake the US and dominate the world” stuff and the details referred to above are part of it, though goodness knows state-driven mal-investment is hardly the preserve of China. Far from it. But there has been enough evidence around to suggest that vast sums of money poured into Chinese projects of this type will not bear fruit. And there will be a reckoning.

Commerce is real. … Aid is just a stop-gap. Commerce, entrepreneurial capitalism, takes more people out of poverty than aid, of course we know that.

– Bono

Madsen Pirie concurs.

Appropriately enough, in a discussion about (Nobel laureate) Paul Krugman, someone mentioned a speech by (Nobel laureate) Hayek that he gave after winning the prize:

I do not yet feel equally reassured concerning my second cause of apprehension. It is that the Nobel Prize confers on an individual an authority which in economics no man ought to possess. This does not matter in the natural sciences. Here the influence exercised by an individual is chiefly an influence on his fellow experts; and they will soon cut him down to size if he exceeds his competence. But the influence of the economist that mainly matters is an influence over laymen: politicians, journalists, civil servants and the public generally.

There is no reason why a man who has made a distinctive contribution to economic science should be omni-competent on all problems of society – as the press tends to treat him till in the end he may himself be persuaded to believe. One is even made to feel it a public duty to pronounce on problems to which one may not have devoted special attention.

I am not sure that it is desirable to strengthen the influence of a few individual economists by such a ceremonial and eye-catching recognition of achievements, perhaps of the distant past. I am therefore almost inclined to suggest that you require from your laureates an oath of humility, a sort of hippocratic oath, never to exceed in public pronouncements the limits of their competence.

Or you ought at least, on conferring the prize, remind the recipient of the sage counsel of one of the great men in our subject, Alfred Marshall, who wrote:

“Students of social science, must fear popular approval: Evil is with them when all men speak well of them”.

This works for all kinds of lauded experts, not just in economics but in climate science, nutrition, psychology and education, for example.

Great minds think alike: I had been meaning to fisk Jesse Norman’s recent defence of the idea that companies have wide social and other “duties” – not just to that nasty stuff about doing what the owners want – but Tim Worstall, at his Adam Smith Institute perch, beat me to the punch. (As readers might have noticed, my Samizdata productivity has been hit by my being very busy at work, and, er, lots of trips abroad lately.) Here’s Tim:

Well yes Jesse: but you’re a Tory MP, not a Labour one. You’re not there to defend the idiocies of the past Labour Government you’re there to try to correct them. This part of the Companies Act was deliberately brought in to try and appease the more drippingly social democratic parts of the Labour Party. Rather than now stating that this is the aim and purpose of a company you’re supposed to be shouting from the rooftops that they got this wrong. The point and aim of a company is the enrichment of its shareholders, nothing else. You should be agitating to get the law changed to reflect reality, not accepting the fantasies of your predecessors: otherwise what’s a Tory for if not to be a reactionary? Alternatively, if we’re to have Tory MPs being so drippingly wet what’s the reason for the existence of the Labour Party any more? Who would need them?

Here is Norman’s original article – in the Daily Telegraph – so readers can judge for themselves whether Tim Worstall has him accurately pegged. He has, in my view.

Companies have no broad “duties” if you believe in private sector, and in a civil society based on voluntary relationships. That means if I set up a firm, with capital of mine or entrusted to me by others with their consent, then apart from not breaking rules about force, fraud, etc, there is nothing else one is required to do. Professor Milton Friedman has this all understood years ago. The proper response to calls for “corporate social responsibility” is “fuck off”.

When Norman talks of a “corporate duty” in some broader sense, he makes no attempt, from what I can see, to validate that by reference any fundamental principles. He is, I see, the author of a new book about Edmund Burke, and he uses Burke quite clearly to push against all this terrible “individualism” (ie, belief in personal freedom) and suchlike that he sees as causing all our problems. Never mind that libertarians/classical liberals have plenty to say about the benefits of a community based on voluntary interaction, not coercion. (How many more times does this have to be explained to the dullards who keep banging on about how we are “atomists”?). It is also well worth remembering that Burke was not a “Conservative” in the sense people today understand it; he was “Old Whig” and friend of the likes of Adam Smith and David Hume, and had little time for economic intervention.

To get back on the nub of the tax/company issue, as Tim Worstall says, if big firms are able to use their accountants and advisors to get around onerous local tax laws, then perhaps Norman and his fellow MPs should consider whether to make local tax laws as simple, and as low, as possible. Another point he ought to consider is something that Worstall again writes about on a regular basis: tax incidence. Companies are not people: if you tax a firm’s profits, then those taxes are paid by people in some way. The taxes are passed on in the form of lower dividends, lower capital gains, crappier products, lower wages paid to staff, shoddier products and services, etc. Norman should consider the sensible ideas of the 2020 Tax Commission.

Norman is a member of a political party that, however dimly, ought to be aware of such basic facts. Yes, I know that many of the Cameroons are utterly useless, but there surely are enough bright Tory MPs who can take Norman aside and explain the basic facts of economics to him. I can think of several MPs well suited to the role. Does Norman have Steve Baker’s contact details?

Addendum: I suppose some on the libertarian camp might argue that calls for corporate duties are what you get when firms receive subsidies, privileges from the state of various kinds, soft loans from central banks, etc. But the solution is not to grant these things in the first place. Simple.

An agency of the US Federal Government, the Economic Development Administration, has as its stated aim:

To lead the federal economic development agenda by promoting innovation and competitiveness, preparing American regions for growth and success in the worldwide economy.

They also want to make, “Investments that promote job creation and economic prosperity through projects that enhance environmental quality and develop and implement green products, processes, places, and buildings as part of the green economy.”

After discovering malware on some computers, they started destroying all their IT equipment:

EDA’s CIO concluded that the risk, or potential risk, of extremely persistent malware and nation-state activity (which did not exist) was great enough to necessitate the physical destruction of all of EDA’s IT components. EDA’s management agreed with this risk assessment and EDA initially destroyed more than $170,000 worth of its IT components, including desktops, printers, TVs, cameras, computer mice, and keyboards. By August 1, 2012, EDA had exhausted funds for this effort and therefore halted the destruction of its remaining IT components, valued at over $3 million. EDA intended to resume this activity once funds were available. However, the destruction of IT components was clearly unnecessary because only common malware was present on EDA’s IT systems.

The cost of the entire episode, including hiring contractors and obtaining temporary replacement equipment was $2,747,000.

This figure will be added onto the USA’s GDP, of course. But we all know that this is not really an exception to the rule that government agencies do the exact opposite of their stated intentions.

See also coverage of this story at Forbes and The Register.

By the way, does it even make sense to attempt to promote both job creation and economic prosperity in the same breath?

Yesterday, I encountered this Economist advert (one of this set), in the tube, which included the following argument that booming Chinese investment in Africa is bad for Africans:

Elephant numbers in Africa are falling fast because of the Chinese demand for ivory.

My immediate reaction was that elephants should maybe be farmed. That would soon get the elephant numbers up again, and it would also be good for Africans, because it would provide them with lots of legal jobs. If you google “elephant farming”, you soon learn that an argument along these lines already rages.

People much like Doug Bandow (and like me) say: Why not farm elephants? And people like Azzedine Downes, as and when they encounter this elephant farming idea, are enraged:

These days, it seems like any idea casually dropped in a coffee break conversation can be, if repeated often enough, and forcibly enough, taken seriously by those not really interested in finding solutions. They are looking for sound bites and this one was a doozy! I have seen these arguments take on a life of their own and so struggled to overcome my own vision of elephants in iron pens being kept until they could be killed for their teeth.

“First of all”, I started. “No-one needs ivory.” “Secondly, your proposal raises so many ethical questions that I don’t really know where to start.”

“Don’t get upset”, he said. “I was just wondering. You are right, it is an awful idea.”

I hope I never hear that idea coming up again and, if I do, I hope it will be just as easy to convince the next misguided soul that it is an awful idea.

I’m afraid that Azzedine Downes is going to hear this notion, seriously argued, again and again, unless he covers his ears.

I think I get where he is coming from. Killing elephants, for any reason, is just wrong, like killing people. Downes doesn’t spell it out, because he is not in a spelling things out mood. (“I don’t really know where to start.”) But it seems to me that what we have here is the beginnings of the idea that certain particularly appealing and endangered and human-like animals should have something like a right not to be killed, just as you and I have such a right. If someone kills us, the government will, depending on its mood, go looking for who did it and maybe, if it catches the miscreant in question, punish them in some way or another. Killing elephants, says Downes, is likewise: murder. See also: whales.

Farming a bunch of humans for their bodily organs would also be murder. A kidney farmer pointing out that he was raising his clutch (herd? pack? flock?) of humans not just for the serial killer hell of it, but in order to profit from selling their kidneys, would make things worse for himself, legally speaking, because this would provide the jury with a rational motive. Motive is not justification. Motive gets you punished, not acquitted.

In the matter of elephants, pointing out that farming elephants for their tusks might, given the facts on the ground in Africa, be the difference between African elephants as a species surviving, and African elephants being entirely wiped out by ivory poachers (for as numbers diminish, so prices will rise and rise), or perhaps entirely replaced by a newly evolved species of tuskless elephants, is, for Azzedine Downes, entirely beside the point. Farmers killing the elephants for their tusks doesn’t solve the problem, any more than the slave trade solved the problem of slavery. The problem of slavery was slavery, and the problem here is people killing elephants, which they would do even more of if they farmed them for their tusks. This is absolutely not just about the mere survival of a species. It is about not doing something morally repugnant. The elephants must be saved. They must not be murdered. End of discussion.

Thoughts anyone? How about the Azzedine Downes tendency proving their love of elephants by buying lots of elephants, and large elephant habitats, and then spending more money protecting the elephants from ivory poachers, but without farming them or otherwise exploiting them, other than as objects of photographic devotion by tourists. Presumably this is sort of what they are already doing, even as the idea of people owning elephants sticks in their throats, just as does the idea of people owning people.

Here’s another thought. How would Azzedine Downes feel about elephants having their tusks removed and sold on to Chinese ivory carvers when the elephants die but not before they die? Die of natural causes, I mean. As a matter of fact, are the tusks of elderly elephants, just deceased, still worth enough for that to be any sort of economically viable compromise? And as a matter ethics, would the Downes tendency tolerate even that?

Elephant tusk donor cards? Well, not really, because how would you know, in this new world of elephant rights, how the elephant or elephants actually felt about such a scheme? In this connection, the recent proposal that humans should be presumed willing to part with any or all of their useful-to-others organs when (as above) they die but not before they die, unless they explicitly say otherwise by carrying a non-donor card, is surely relevant.

Another thought: Will it soon be possible to make something a lot like ivory with 3-D printing? Or with some sort of magical bio-engineering process? Perhaps, but if so, that would presumably take much of the fun out of ivory. But then again, so might ivory farming, if it got too efficient.

Perusing the Samizdata postings category list reminds me that maybe similar considerations apply, or soon will apply, to hippos.

Time for me to stop and for any commenters, who want to, to take over.

If big government were the key to economic success, France, with more than half of its GDP accounted for by government, would have rapid economic growth rather than an unemployment rate of 11 percent and negative growth. Yet France, Britain and the United States are demanding that the low-tax jurisdictions increase their taxes on businesses. They also demand more tax information sharing among countries. The officials of the G-8 assure us — as if they think we are all children or fools — that sensitive company and individual tax information will be kept confidential and not be used for political targeting, extortion, etc. The U.S. Internal Revenue Service had a reputation for being less corrupt and less incompetent than tax agencies in many other countries, which only illustrates how low the global standard is.

– Richard Rahn, the Tyranny of the Taxers

There is, in this world, something called the Budweiser trademark dispute. The giant American brewery Anheuser-Busch produces a beer named Budweiser, an industrial mass produced lager that is not greatly revered by beer connoisseurs but which sells in large quantities, and a brewery called Budweiser Budvar Brewery in the Czech city of České Budějovice (Budweis in German) produces another beer called Budweiser, which is considered an excellent beer by most beer lovers. The two breweries have been fighting in courts throughout the world with respect who has the right to the name Budweiser ever since the end of Communism in Czechoslovakia. In some countries the Americans have won and the Czechs have had to find a different name, and in others the Czechs have won and the Americans have had to find a different name. In Britain the courts have made the eminently sensible ruling that both brewers can use the name and drinkers are smart enough to be able to tell the difference, but I don’t believe this has happened anywhere else.

Beer lovers are often sympathetic to the claims of Budvar, because the beer is better and because it actually come from Budweis, and this is therefore the “Original Budweiser”.

This is not really true, however. Anheuser-Busch started brewing the American Budweiser in 1876, due to the fact that the beers of Budweis were famous, including amongst German Americans. However, the Budvar brewery did not exist at that point. This brewery was not founded until 1895. At some point after that, they also started using the name Budweiser, possibly because the name had been given further fame by Anheuser-Busch. At least to some extent, the Czechs at Budvar may have started using the name because of the use of it by Anheuser-Busch, and not the other way round. Budvar was founded by ethnic Czechs, and the only reason they would have had for using a German name was that the German name had already been made famous by other brewers.

However, what of those earlier beers from Budweis, responsible for Anheuser-Busch starting to use the name? Well, there is another, much older, brewery in Budweis / Budějovický Budvar. This brewery, known as Budweiser Bürgerbräu until 1945, made beer in Budweis under the Budweiser name at least as early as 1802. It is almost certainly this company’s beers that Anheuser-Busch was copying when they started using the name “Budweiser”. This brewery was run by ethnic Germans from its founding until 1945, after which it was taken over by ethnic Czechs and de-germanised. The brewery is now called Budějovický měšťanský pivovar, which is a precise Czech translation of its original name. When de-germanisation took place, the brewery ceased using German words and names, including “Budweiser” (it regained some interest in using them post-1989). However, this brewery has by far the strongest claim that it produces the beer that is the original Budweiser.

That said, the trademark battles between the other two, larger companies have been so ferocious that Budějovický měšťanský pivovar has stayed clear of them, despite apparently having a stronger claim to the name than either of them. The brewery is quite a substantial one, and produces a significant quantity of (excellent) beer. It sells the beer under a variety of names including Crystal, Samson, B.B. Bürgerbräu, Boheme 1795, and more. It only uses the word “Budweiser” in places where trademark law is weak.

This is why I took the above photo, in Tbilisi in Georgia last month. It was certainly not the first time I had consumed beer from the brewery that actually gave us Budweiser, but it was the first time I had ever seen beers from that brewery actually using the word. It is not the most prominent word on the label, perhaps, but it is still prominently there.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|