We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Another US state has legalised gay marriage. Am I supportive? Well I am happy the state is not prohibiting people from marrying whomsoever they wish but… no, I am not delighted because it just compounds an existing error by extending state sanctioning of marriage to even more people.

My problem is not that homosexual people can now get married but rather that another golden opportunity to get the state out of the marriage business completely has been missed. If two people get married, it is the businesses of those two people and NO ONE ELSE. For all I care people can ‘marry’ anyone who can reasonably bind themselves to a contractual relationship and say “I do” .

The only win-win solution is that people stop accepting the state has any right whatsoever to ‘sanction’ marriage between two consenting people. That means people can regard themselves as married if they both agree and to hell with what anyone else thinks… and if others choose not to accept that those two (or three or four) people are married, due to whatever prejudices they subscribe to, well that is purely their business too.

Within hours of the July 7 2005 bombings in London, the BBC stealth-edited its reports so that any references to “terrorists” that had initially appeared were changed to “bombers” or a similar purely descriptive, non-judgmental term. This was done in response to a memo from Helen Boaden, then Head of News. She did not want to offend World Service listeners. Given this reluctance to use the word “terrorist”, suspended for a few hours when terrorism came to its front door and then reimposed, I often wondered what it would take for the BBC to rediscover the ability to use words that imply a moral judgment.

One answer was obvious. It was fine to describe bombing as a “war crime” if it was carried out by the Israeli air force.

But in general as the years have gone by the BBC stuck to what it knew best: obfuscation. For instance, this article from last December, describing how fifteen Christians had their throats slit in Nigeria described the perpetrators as the “Islamist militants Boko Haram”. In venturing to describe the murders as a massacre, that article went further than most; the bombings of churches in Nigeria by Boko Haram are routinely described in terms of “unrest”, or as “conflict” – as if there were two sides killing each other at a roughly equal rate.

However, on Sunday I observed something I had not seen before. An atrocity carried out by Muslims against Christians was described as an “atrocity”. It happened in 1480, but still.

The BBC report says,

Pope Francis has proclaimed the first saints of his pontificate in a ceremony at the Vatican – a list which includes 800 victims of an atrocity carried out by Ottoman soldiers in 1480.

They were beheaded in the southern Italian town of Otranto after refusing to convert to Islam.

A reminder that “martyr” used to mean someone who died for his faith rather than killed for it. A reminder also of a centuries-long struggle against invading Islam that has been edited out of our history. You can bet the Seige of Vienna, which proved to be the high water mark of the Ottoman tide, does not feature in any GCSE syllabus. Nor does the rematch one and a half centuries later. The epic Seige of Malta was once celebrated in song and story, but don’t expect to see a BBC mini-series about it any time soon. Damian Thompson recently said a lot of what I had been thinking when he wrote about the the mass canonisation of the martyrs of Otranto in the Telegraph (subscription may be required):

Martyred for Christ: 800 victims of Islamic violence who will become saints this month

The cathedral of Otranto in southern Italy is decorated with the skulls of 800 Christian townsfolk beheaded by Ottoman soldiers in 1480. A week tomorrow, on Sunday May 12, they will become the skulls of saints, as Pope Francis canonises all of them. In doing so, he will instantly break the record for the pope who has created the most saints.

I wonder how he feels about that. Benedict XVI announced the planned canonisations just minutes before dropping the bombshell of his own resignation. You could view it as a parting gift to his successor. Or a booby trap.

The 800 men of Otranto – whose names are lost, except for that of Antonio Primaldo, an old tailor – were rounded up and killed because they refused to convert to Islam. In 2007, Pope Benedict recognised them as martyrs “killed out of hatred for the faith”. That is no exaggeration. Earlier, the Archbishop of Otranto had been cut to pieces with a scimitar.

Thompson continues,

There are, however, good secular reasons for welcoming this canonisation. Our history is distorted by a nagging emphasis on Christian atrocities during the Crusades combined with airbrushing of Muslim Andalusia, whose massacre of Jews in 1066 and exodus of Christians in 1126 are rarely mentioned. Otranto reminds us that Islam had its equivalent of crusaders – mighty forces who nearly captured Rome and Vienna.

The Muslim Brotherhood is still committed to a restored Caliphate; this week its supporters prophesied the return of a Muslim paradise to Andalusia. These are pipe dreams, it goes without saying. But they matter because they inspire freelance Islamists whose fascination with southern Europe has nothing to do with welfare payments. They think of it as theirs because they know bits of history that we’ve forgotten.

Our amnesia comes in handy in dialogue with Muslims: we grovel a few apologies for the Crusades, sing the praises of the Alhambra, and that’s it. But what does this self-laceration achieve? Arguably it’s counterproductive, because it shows Muslims that we’re ashamed of our heroes as well as our villains. Which is why the mass canonisation of 800 anonymous men is so welcome: it ensures that, even though the West has forgotten their names, it won’t be allowed to forget their deaths.

In the latest attempt by the Obama White House to recapture the glory days of the Nixon administration, it has been revealed that the US Department of Justice went on a fishing expedition into the telephone records of the Associated Press. They learned who everyone that any AP reporter using one of the telephones in question spoke to for months.

Government obtains wide AP phone records in probe.

As it happens, this is against the law. According to 28 CFR 50.10: “”No subpoena may be issued to any member of the news media or for the telephone toll records of any member of the news media without the express authorization of the Attorney General.”

What are the odds anyone will even be mildly disciplined for this? Zero, I’d say.

David Cameron’s position is that he is trying to persuade the Golf Club to play tennis, but that if they refuse, he will continue to play golf.

– Michael Forsyth, on Daily Politics today, describing the posture of the Prime Minister with regard to the European Union.

It often seems as if our opponents live in a different universe. Perhaps they do.

There is at the moment a serious controversy in the US about the way in which certain Internal Revenue Service persons harassed – that is not putting it too strongly – certain groups, such as Tea Party activists seeking tax-exempt status. And it appears other groups, according to this article in National Review, have been targeted.

This is all very bad, and I am sure that those who are calling for heads to be put on spikes, so to speak, are justified. Tar and feathers, etc. However, it occurs to me that political conservatives/libertarians who complain – with plenty of justification – about the bully-boy tactics of the current Obama regime are in danger of missing the chance to frame the argument in a broader way. Surely the problem is that if any group, of any political colour or leaning, applies for tax-exempt status, then that is playing to the fundamental problem with the tax regime in the US (and for that matter, in other countries where similar tax regimes operate). The problem is that taxes are relatively high, so that getting a tax-exemption is worth a lot of effort and lobbying (and the potential for corruption is obvious). And the bureaucrats therefore get a lot of power in deciding what is, or what isn’t, a tax-exempt organisation.

Surely a way to cut out the need for all this activity is to sweep away the whole system of loopholes, exemptions and special status for for this or that organisation, and institute a flat-, low-tax regime. No exemptions, nada, zip, nothing. Just a simple system that requires far fewer people – such as leftist IRS officials – to operate. Besides removing the potential for mischief-making by such officials, it means we can sack a lot of bureaucrats, saving the public a great deal of money and removing the deadweight cost of a hideously complex tax code.

The IRS scandal over the targeting of the Tea Partiers and others certainly suggests that recently enacted – and complex legislation – such as the US FATCA Act (which targets expat Americans working abroad) could be misused to go after anyone who, for whatever reason, gets on the shit-list of the government of the day. Not an encouraging thought.

But conservatives and libertarians must do more than just moan about the abuses of such powers. It often bemuses me how we are told that conservatives and particularly anarchic or “atomistic” libertarians just don’t get the importance of institutions and the complexities of civil society, etc, etc. But institutions can mestasise into malignant forms, especially where the operation of coercive force, and receipt of privileged sources of income, is involved. In office, conservatives, such as Britain’s Tories or the US Republicans, often fail to deal with, or even better, abolish, those institutions which have become malignant and do them, and the countries they get to lead, a great deal of harm. Just as the Tories have allowed organisations such as the BBC to run on, with privileges unchecked, for years, so the Republicans in the past have missed a trick by not reining in the IRS.

It may be that the IRS cannot be easily abolished outright – which would be the best option – but this institution is is in dire need of drastic shrinkage and simplification. I should have thought that promising to achieve such changes would be a sure vote-winner in forthcoming elections.

I liked these thoughts from Timothy Sandefur and it is worth quoting them at length:

The problem, it seems to me, is that while there is much to be said for pursuing in work what you love in life, a lot of people seem to assume that their “passions” will just come to them like a bolt from the blue. At some point, they seem to imagine, you just wake up knowing what you love, and then you’re able to plan a career around that.

But it does not work that way. Instead, you discover only after doing things that there’s something you love to do. The point of a broad exposure to different ideas, pursuits, and cultural influences during your education is to enable you to discover what it is you love doing—which, of course, will come only after doing many things that you don’t love. You don’t just somehow know that you want to be an architect because building is your passion, or decide that researching the history of coal mining in upper Silesia or the genetic diseases of fruitflies is what you love to do. Instead, you read a book about architecture or European history or medicine, and that leads you to another book or to a lecture or to a documentary film, and then you take an intro class at your community college, and get a summer internship at the Silesia Cultural Foundation…or whatever the story. You go from one discovery to the next, exploring your way forward. You must discover your passion—it isn’t handed to you. And you only discover it by trying things and being patient and allowing that discovery to bubble up from underneath. That involves a lot of work and a lot of trial and error and a lot of dead ends, sometimes. But that is true of all things in life. Often you do not realize that you have a passion for a particular thing until after you’ve been doing it for a long while. To say you don’t know what job to pursue because you don’t know what your passion is is like saying “I know I should marry a person I love, but what if I don’t have a person I love?” or “I know I should eat food that is palatable to me, but what if I don’t know of a food that’s palatable to me?” You have to go out and find these things; work to discover what you love to work at. Yes, that’s sort of a bootstrap paradox. But it’s still the only way it can be done. The idea—pushed by inspirational posters and Hollywood—that you just know what you want from life and go out and get it, is misguided and ultimately self-defeating.

I should add that one of the reasons for my being rather crap in updating posts on Samizdata lately is that I have become so incredibly busy with my day job that time has been short. But I love what I do – most of the time anyway – so this is part of the deal that I have to arrive at. I am in Malta at the moment and recently met the guys who run a hedge fund business focused on Bitcoin. They seem a very smart lot, and I’ll pass on my thoughts a bit later.

In my ongoing quest to read science fiction with sensible politics and economics, I thought I would give Robert Charles Wilson a try and am reading his novel Spin, which is very enjoyable so far. On his web site he has published some talks he has given, including this:

Total up the man-hours necessary to bring even a cheap conventional color TV into your home, and the result, I suggest, would be absolutely staggering. And that work in turn rests on an absolutely colossal body of prior knowledge, all of it generated piece-by-piece and preserved and transmitted over generations.

This reminded me of the famous pencil essay. He is writing about all the things that went into making a TV advert for a car:

So even something as inherently humble as an automobile commercial stands as striking evidence that we, as a species, have an absolute genius for collaboration. Even without conscious intent — and after all, of all the billions of people necessary to produce that ad, only a handful of them actually wanted it to exist — we can still create something in which our collective ingenuity is embedded and embodied.

Of course, he doesn’t mention what mechanism makes this collaboration possible, but we all know what it is.

“Dear incompetent ninny …” No. “Dear complete imbecile …” I suppose not. “Dear feeble-minded simpleton …” I’d better not. Well, fine, then. “Dear State Representative …”

– Here via here. (I must declare an interest however. Another of the quotes in that second “here” was from here.)

This is actually quite profound. We are often tempted to get angry with state functionaries. But since we are usually begging things from them, rather than demanding them in the manner of one who could take his business elsewhere – with the state there is no elsewhere, we usually choose to remain polite. And if we finally get what we are begging for, we tend to be effusive in our thanks, if only because so pleased that the ninny did something less than completely ninny-ish. The result is a world in which state functionaries genuinely imagine themselves to be loved by almost all of their victims and hated by hardly any of them.

Incoming from Rob Fisher (to whom I owe him a blog posting about this talk that he gave at my home a while back – short version: it was very good):

Finally I found a video that explains to my satisfaction what using Google Glass is like. It’s a display that you wear, that uses clever optics to give the appearance of looking at a 25 inch screen 8 feet away.

Parts of this video are welcome-to-the-future moments.

By the way, these voice commands already work on your phone; tap the microphone symbol top right and say something like “wake me up at 8am”.

My phone being the Google Nexus 4 that I have been going on about lately, for example in the previous posting here.

I won’t be watching this video in the immediately immediate future as I have other things to be getting on with. But I definitely will very soon.

What Rob says about voice commands is interesting, I think. I have long suspected that a big computer leap would occur when we stopped communicating with computers by typing on them, and instead just talked to them. “Jeeves, what’s that thingy where the thingamajig I was talking about yesterday is yellow instead of black?” “Do you perhaps mean this, sir?” “Yes, that’s the thing. You’re a genius Jeeves!” “One does one’s best sir.” Etc.

From time to time I do Samizdata postings about how rapidly technology is advancing these days. Recently I stuck up an SQotD on the subject. Here is another such posting. Basically it’s two pictures.

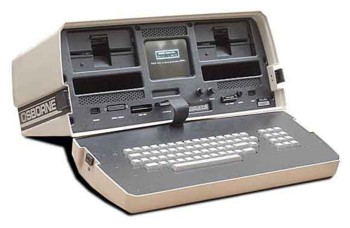

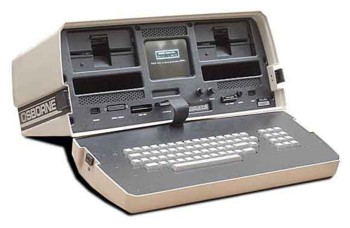

The first is a picture of my first proper computer (I do not count the Sinclair Spectrum), purchased in about … 1981? This computer, an Osborne 1, consisted of a very small screen, a keyboard, and about half a ton of electrical gubbins, including two disk drives, each accommodating disks that were, I seem to recall, 256kb in capacity. 256kb was a lot of kb in those days.

The second picture is of my latest computer, which is a Google Nexus 4, plus a couple of bits of plastic to prop up the Google Nexus 4, plus a keyboard:

For me, the killer app of all computers has always been word processing, the ability to type a piece of writing into a machine, and then to modify and expand the piece at will, and only when it’s nearly finished have it automatically printed out. And then printed out again if you need that, as you almost certainly will. Amazing. (This being the twenty first century, you may want to read “print out” as “publish”.)

My first “word processor” (the inverted commas because word processing as we now use that phrase was exactly what it couldn’t do), which I used for about a decade, was an Olivetti typewriter. For this I paid twenty five quid, which is about the same as what I recently paid for the Google Nexus 4 after you include inflation. For those who do not know what a “typewriter” is, the basic rule was that the only way you could store the words you had thought of, in the order you wanted them in, was to print them all out, one letter at a time, as you thought of them. The switch from that to the Osborne 1 remains the single most exciting technological leap of my life, although the arrival of blogs runs this a close second.

As for the smallness of the screens of both these computers, well, each to his own, and I entirely get why many would hate to process words on such a tiny thing as the Google Nexus 4 or with a screen as tiny as that of the Osborne 1. But I loved the small Osborne screen. There was something very appealing to me about those tiny little letters, so much more so than the big clunky letters on other computers of that era. Me being short-sighted, the distinction that really matters to me is not big-screen-versus-small-screen; it is screen (however big) far away: bad, versus screen (however small) near: good. And if the Osborne was not in any very meaningful way “portable”, it was at least, to use a word from those days, “luggable”, from one work top to another, as and when the need arose, which for me, then, it often did.

And just as I loved the tiny old Osborne screen, I now rather like the Google Nexus 4 screen. But of course what I really like about the Google Nexus 4 screen is that, since a tiny screen is all that it is, it is so light and so small that I am happy to carry it around in case I need it to process any words, even if I never actually do, on that particular expedition. For me, in my present aging and physically weakened state, the difference between a computer too heavy to carry around without being irritated by it unless I use it, and a computer so light that its weight is not a problem even if I don’t touch it all day long, is a big difference. Even today’s small laptops – minute compared to the Osborne – fail this test, for me, now.

The beginnings of this posting were mostly typed into the second of the two computers pictured above, before being transferred into my regular non-portable computer, the one that resides permanently in my kitchen. I am still amazed at how well this transfer worked, the very first time I tried it. While I was doing the transfer, it looked as if all the paragraphing would be lost, but when I pasted everything into a text file on the kitchen computer, there it all was, just as it began. Magic.

In addition to being a word processor, the Google Nexus 4 is also, as already noted, a telephone. And like all mobile telephones these days, it can also send what used to be called telegrams. It is also an A-Z Guide to London, and a map of the Underground. The map even works, unlike an A-Z of London, when I venture outside of London. It tells me when the London bus I await will reach me. It is a mini web-browser, a mini-Kindle, and a means of posting relatively straightforward postings to my blog or (when I have worked that out) to this blog. It is a gadget for identifying music recordings just by it listening to them, being just as good at identifying classical recordings as it is a identifying pop. It is even a rudimentary camera. All of which makes it that much more likely that I will use my Google Nexus 4 for something during just about every expedition I go on. The old Osborne 1 could do none of these things. But you knew all that, and much else besides which I have yet to discover. You get the pictures.

I am, of course, not the only one who has noticed how well technology is doing these days compared to politics. If you look for this particular meme, you see it everywhere. Here is a whole book with that notion as its starting point, linked to recently by Instapundit. (Who, by the way, also linked to and recycled that SQotD. I thought he might like that one.) Says the author of this book, Kevin Williamson:

Why are smart phones so smart – getting better and cheaper every year – while our government is so dumb? Is there a way to apply the creative and productive institutions that produced the iPhone to education, public schools, or Medicare?

He thinks there is, as do I. More from and about Williamson here.

LATER: Instapundit quotes Williamson again:

We treat technological progress as though it were a natural process, and we speak of Moore’s law — computers’ processing power doubles every two years — as though it were one of the laws of thermodynamics. But it is not an inevitable, natural process. It is the outcome of a particular social order.

Do you wonder that fish spoil when wrapped in the Guardian?

– Samizdata commenter RRS

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|