We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Today, I was at a small conference called Turning the Tables on the State held by an organisation called A World To Win. I had been asked to give a presentation on the British government’s plans for Identity Cards and a National Identity Register, which I duly did, and got a few laughs. I’m glad they are supportive of NO2ID, I really am. But I also attended the rest of the conference, which was a strange, strange experience.

Here were all these fairly pleasant, not obviously mad or stupid, people, saying things I wholly agree with about threats to civil liberties. But at the same time most did not leave it there. The presentations were larded with nonsensical quotations from Marx yanked out of historical context and treated as eternal wisdom. The threat to liberty and the constitution could not be anything so mundane as the lust for power and institutional convenience. It must be driven by transnational capitalism’s need to increase its exploitation rate by invading the public sector.

And the ‘rights’ to be defended against monolithic global finance are apparently mostly not of the “first generation rights” – the liberties (correlative of no-right of others to interfere) that most readers and writers of this blog exalt. They are prescriptive rights, to free education, to work, to fair remuneration for that work, etc., etc. And that is what most astonished me.

While rightly distressed by the power of the state being used to impose expressible views and appropriate ways to live on the citizen, these kindly people see no irony in seeking institutions to force their values onto others, in the name of the people. Wish-lists abounded, their real implications for personal lives unconsidered. But the most startling positive right I’ve ever heard suggested was from the report of a discussion group:

We need a right to a rich interior life.

It has it all – from aeroplanes that look like they are crashing to exciting political rallies – wouldn’t YOU rather go to North Korea?

Update: The official DPRK website hates our links for some obscure reason. So, in the interests of spreading the happy holiday message, please copy and paste this URL into the appropriate spot…

http://www.korea-dpr.com/kfa2006/kfadelegation05.wmv

This is a fascinating mystery story. As someone who loves books and has worked in publishing, I have long been perplexed by the massive sales of leaden conspiracy ‘thrillers’ (as I have to write it, being really very ungripped) and of pseudo-histories.

These are strange alien artefacts in the literary world. They appear to be books, having the same physical manifestation. Yet the words in them have no rhythm, and make no sense, the world they portray is all surface, all banality: all invented, but paradoxically without imagination.

The familiar book, grounded in fact or rich in fiction, sells (mostly slowly) to an audience that comes back for more books. These… I need another wordname… reads are bought in vast numbers by people who do not otherwise read. You see them swarming on the tube, at bus-stops, in advertisements as book-club special offers, everywhere. And then they are gone. Where?

Few have the life-span of a book, it seems. But where do they go to die? They are seldom seen in second-hand shops. And why are they so successful when they are plainly so inbred?

The genus is so narrow that there’s always been some doubt in my mind whether it is two species or one. Now a strange court-case may inform us on that matter (if not why the infernal things are so popular). It appears that two of the authors of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, a “non-fiction” work of non-history, are suing in the High Court the writer of a fictional read called The Da Vinci Code for copyright infringement.

If the author of a history book were to sue an historical novelist, then we would expect it to be on the ground that passages of text were quoted without permission. For use of expression, not content. There is no copyright in facts.

But weirdly that’s not what is going on here. Jonathan Rayner-James QC for the plaintiffs said:

HBHG is a book of historical conjecture setting out the authors’ hypothesis. The authors’ historical conjecture has spawned many other books that developed aspects of this conjecture in a variety of directions. But none has lifted the central theme of the book

Which is what Dan Brown is accused of.

What could make “historical conjecture” original work capable of copyright protection? Only that it bears no relation to history, it seems to me. Can it really be the plaintiffs’ case that the novel is not novel enough, because their read – sold all over the world labeled ‘non-fiction’ – is in fact a fantasy?

If that is their case, and that case prevails prevails, then I am interested to know what the publishers of HBHG, HarperCollins who also published The Da Vinci Code and are joint defendants, might do. Did their contract with the plaintiffs contain that standard apotropaic against libel, a warranty from the author that “all statements purporting to be facts are true”? The consequence for the pseudo-historical read as a genre could be interesting.

Extinction of the species would be too much to hope for, I suppose. But for once a thriller has me gripped.

This is a poster I saw the other day, outside St James the Less, which is a church very near to where I live. And no, I am afraid I do not know what “the Less” means, although perhaps a commenter will.

What I found bizarre was how they describe God. They do not come over as monotheists. They make it seem like there are lots of gods (with a small g) to choose between, and they chose a big one. Or maybe they have a big god of their own stashed away somewhere.

Interested? Here is the website. Although “equipping through ministry for mission” does not sound like much of a slogan to me.

‘Stoatman’ from ‘Zuid Holland’ writes in with a remarkable bit of hypocrisy from the Human Rights Industry

Amnesty International, as part of its ongoing struggle for universal human rights, is looking to employ a Discrimination and Identity consultant for its Dutch branch.

The Discrimination and Identity team consists of three paid and two volunteer positions and is concerned with influencing government policy and societal views regarding discrimination on grounds of skin colour, ethnicity, religion, gender, and sexual orientation. … In this position you will develop policy and strategy in the field of Discrimination. This includes research into discrimination, and the development and organisation of lobbying regarding the fight against discrimination in the Netherlands. You will also be responsible for the development and implementation of actions and campaigns concerning discrimination worldwide and in the Netherlands

Before you dust off your CV which bulges with non-jobs in local government and crack open the Dutch taped course, there is just one problem before you can claim your £21-26k salary:

Considering the composition of the team, we are seeking someone from an ethnic minority group

Has it reached the stage now that such discrimination has become so mainstream that nobody even bats an eyelid to such brazen hypocrisy?

(hat tip – The Amazing Retecool)

You may have already heard this but I laughed out loud when I came across this: an officer involved in Dick Cheney’s recent difficulties is called Captain Kirk.

Phasers off, gentlemen.

Heh. Who was that speaker again?

From an email circular promoting think-tank events around Europe:

London

21/02/06 Policy Exchange “Why the Agenda of the Future cannot be delivered by a person stuck in the Past” – William Hague MP, Shadow Foreign Secretary

RSVP: info@policyexchange.org.uk

Lynn Sislo:

Some people might find this site disturbing but I trust that there will be no rioting.

Indeed.

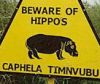

So if hippophobia is a morbid fear of horses… what would a morbid fear of hippototamii be known as?

I wrote to the Department of Culture, Media & Sport (!) back on 10th January to nominate the CCTV camera as an ‘icon of England’… and they have just written back accepting the nomination.

Interesting.

… in October of last year and nothing happened.

So obviously it took a while for the people who wanted to blow this up some time to get all those highly inflammable Danish flags made and organise the outrage. Maybe we are looking in all the wrong places for the people behind this. Radical Islamic clerics? Nah, it was all a conspiracy by Middle Eastern flag makers.

Exhibit A from the United States. That 100 pattie burger looks tasty…

(Spotted on Marginal Revolution)

Exhibit B from the United Kingdom – wait a few seconds to be diverted.

Both sites for the epicureans amongst us, most certainly.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|