We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

One of the few policy areas where the current British government at least appears to be making some headway is education. Here is an article by Toby Young, describing what he confidently believes is such progress, and I hope he is right. (Earlier thoughts by me here about Toby Young’s educational ideas and efforts here.)

Whether, in the longer run, these new free schools will go anywhere especially good remains to be seen. Two thoughts about them occur to me.

First, the customer is still, at least partly, the government. Government money follows the choices of parents. But what if a future government, rather than going to the bother of totally shutting down such schools, started instead following its own money and demanding all kinds of relatively subtle changes and impositions, with a view to grinding them down a little less publicly, and then blaming them for the failure that was inflicted upon them? That’s not at all hard to imagine.

When truly free markets start, they often do so in a very muddled way. Only when the worst of the muddle is sorted does progress then get seriously under way. When, on the other hand, there is immediate improvement, of the sort that Toby Young describes in his article, that can mean merely that government employees have been replaced with other government employees. At first, the new government employees do a better job. Later, progress falters, and eventually things start getting worse, again. The best public bid becomes replaced by the most enticing private bid, made covertly to the politicians. There’s been a lot of that lately.

It is tempting for right wingers to assume that, merely because the slighted government employees – in this case the old school unionised state teachers – are angry about having their monopoly snatched away from them, that the new approach must necessarily be a wholly good thing. Sadly, it does not follow.

My second thought concerns the rules that these new free schools must follow. My question is: Are they allowed to threaten expulsion to pupils they decide they don’t want to keep? I can find no answer in Young’s piece, but suspect that they probably can. If that’s right, then that really is a huge step in the right direction, towards freedom of association.

That may sound an unnecessarily depressing, even belligerent, way to talk. But in schools, in my limited but still very real and quite recent experience, the right to expel is the biggest single difference between success and failure.

Paradoxically, if you can expel, you very seldom actually want to, because the mere hint of the threat solves your problem. But if you cannot expel, you cannot threaten it either, and problems then multiply. Add that to the fact that, quite properly, you also cannot threaten tortures of the sort that used to be routine in schools but which are now frowned upon (like severe beatings or solitary confinement or compulsory hard labour), and the school has literally no power over its pupils, other than its power to amuse. As soon as those pupils work that out, the ones who prefer mayhem to learning or even to being otherwise entertained become the rulers of the place. There is simply no way to control them. At that point, just about everyone involved wants out of there.

I have personally witnessed this kind of thing, when doing various stints of volunteer teaching. The problem was not the age of the pupils or the incompetence of the teachers. In other circumstances the same pupils would have behaved fine, and in other institutions the teachers would have done fine work, a fact that many failing teachers act upon, thereby becoming successful something elses. The problem was the rules.

If Toby Young’s school is obliged to go on attempting to educate whichever pupils they are at first happy to welcome but later wish they hadn’t, then look out Toby Young. Trouble. Just as corruption and monopolised failure takes a bit of time to organise, so too does it take time for pupils in a place like Tony Young’s school to work out that the people bossing them around are actually defenceless against determined rebellion, if that is the situation. But if that is the situation, the pupils will work it out, and that will have consequences, of the sort that Toby Young will not like at all.

If, on the other hand, Toby Young and his comrades can simply say to such potential rebels: “Our gaff – our rules – break our rules and ignore all warnings, and you’re out”, then the problem won’t even arise, because the mere hint of expulsion will end such problems at once.

Expulsion is the opposite side of the coin to the right to leave, the coin being (see above) freedom of association. Freedom of association is, I think, one of humanity’s very best ideas. If all those present in some institution prefer, however grudgingly, being there to not being there, and if everyone there is tolerated, however grudgingly, by everyone else, then everything just works so much better. There may be lots of other problems, but tackling them becomes so much easier if all those who don’t even want to solve those problems can be told to get the hell out of there, or can just get the hell out anyway.

All men dream: but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake up in the day to find it was vanity, but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dreams with open eyes, to make it possible.

– T. E. Lawrence

Quoted – I kid you not – near the end of this video interview by South African cricketer A. B. de Villiers. The three match series between England and South Africa, featuring six of the world’s top ten Test bowlers and eight of the top seventeen Test batsmen and which will will decide which team is ranked No 1 in the world, begins today at the Oval.

Early yesterday evening, taking advantage of a small window of nice weather in our mostly appalling British “summer”, I took a stroll across the river. I ended up in the London Bridge area, where, just before descending into the Tube to go back home, I took this picture:

That is a church called Saint George the Martyr.

Now, you may think that this church is behaving itself, but actually, it is seriously interrupting the view of the recently completed Shard. To show you what I mean, here is another picture which I took seconds later:

Now you see it, now you don’t.

I’m just kidding (I had in mind sentiments like this) about the church being an eyesore. Saint George the Martyr looks very nice, and I find these two buildings particularly pleasing when they are thus aligned.

Earlier I had taken another picture of St George the Martyr and the Shard, but from further away. The church looks smaller, just as you would expect. But the Shard looks bigger the further away you get from it, because it becomes so much clearer that it actually is so very big, and so much bigger than everything else.

My more serious point is that the Shard, far from being an alien and intrusive presence, actually fits into big old London very well indeed, not least because it echoes some of London most characteristic and most loved architectural shapes. That’s what I think, anyway.

Some declare themselves offended by the Shard, as has already been noted here. But for me, London without its recent crop of skyscrapers would be a less appealing and far duller place. Had the Shard only got as far as the pretend photo stage, but had it never actually materialised, I’d have been very sad. If lack of money had caused that, well, that happens, when boom turns to bust. But had the Shard been politically aborted because of its alleged aesthetic offensiveness, I would have been offended myself.

Earlier this week I watched a television show which was advertised as being about London’s underground railway system, and the technology that made it possible, but which was really about underground railways in general.

I really, really enjoyed it, when it was first shown on Wednesday night. And I am writing this in some haste because the show is being shown again tonight, at 7pm, Channel 5. If you love stuff about high tech engineering and the extraordinary ingenuity and cunning and (not least) bravery and physical endurance that goes into it, then watch it. Or (if you have a life) set your video, or whatever videos are called these days. (Or be twenty first century about it and watch it on the www, which I can’t do because of something about my computer blocking adverts.)

My favourite bit was when they explained how a noted French engineer with the delightful name of Fulgence Bienvenue put a tunnel through the bank of the River Seine in Paris. Problem: the bank was not made of proper earth. It was made of mud. How do you drill a big tube through mud? Answer: you freeze the mud, and then drill through it, insert the tube, and … well, job done. By the time the … I was going to say permafrost, but make that tempafrost … has turned back into mud, the tube is in there and train-ready.

Another major engineer whom I’d never heard of until now also got a well deserved pat on the back from the television. This was an American called Sprague:

Hailed during his lifetime as the “Father of Electric Traction” by leaders in the fields of science, engineering and industry, Frank Julian Sprague’s achievements in horizontal transportation were paralleled by equally remarkable achievements in vertical transportation.

In other words, Sprague didn’t just make underground trains work far better by replacing one massive steam engine at the front with lots of far smaller electric engines all the way along the train, which as I am sure you can imagine worked far better, not just because of all that steam, but also because it meant the trains could be as long as you want. He also pioneered electric engines for lifts, as we call them over here. As a result of Sprague’s elevator engines, skyscrapers scraped the sky a lot more than hitherto, as was well explained in this TV show.

The bit at the end about how they squirted a new concrete foundation under Big Ben, to stop it falling over when they were sticking the Jubilee Line extension right next to it, was not so epoch-making. But it was fun.

Today’s SQotD is already taken, and in any case yesterday’s SQotD was also about banking, but here is more quotability, from regular quotee here, Steve Baker MP, writing for the Spectator Blog about the LIBOR scandal:

The really important question today is not whether the Bank of England encouraged manipulation of credit markets by self-interested rogues but why we tolerate systematic credit market manipulation by the central banks as a matter of policy: nowhere else in the economic system would we accept explicit planning of the price and quantity of a vital commodity. If it worked, we’d all be communists.

In the Cobden Centre round robin email flagging up this piece, the words “linked from Guido” were included in the email title. This stuff is not merely being said, relentlessly. It is getting around.

Here is some further evidence of that, from the BBC:

A popular solution to the financial crisis has been to print more money, but is there another way of fixing our economy? Would the financial system be more stable if each pound, dollar or euro in our pocket was once again backed by gold?

And they go on to provide the answer given to them by Detlev Schlichter: yes.

All of which confirms the Austrianism as Number 2 meme.

LATER: More incoming from the Cobden Centre flagging up this programme, the first part (of two) of which will be shown at 9pm on Channel 4 this evening. Various Cobdenites contribute. Plus, see also this.

Here:

Beijing Olympics officials approached the 2008 Games as an opportunity to host the world’s biggest sporting event, not to create infrastructure of permanent importance. Now Beijing is left with a post-Olympics landscape that better suits the taste of ruin porn aficionados than urban development officials. Its a story that should serve as a warning not only to London but future cities that have their sights set on investing billions into new infrastructure for a two-and-a-half week event.

I do wish people would be less free with that word “invest”, when what they actually mean is “spend”. But you can’t blame this particular guy, for our entire Keynes-soaked culture is saturated with such confusion. The modern Olympics are a gigantic exercise in digging huge Keynesian holes, running about in them, and then filling them in.

Ruin porn pictures follow.

I’m actually a tad more optimistic about London’s Olympic “infrastructure”. Our Olympic clutter will cost us many arms and many legs, for little immediate benefit or longer term benefit. And presumably, in the short run, our Olympic leftovers will suffer some disrepair and delapidation. But most of it is in a part of not-outer London that will be simply too valuable to be left to rot indefinitely. Also, our media will sneer too much if what now appears to be happening in China were to happen here. In China, media sneering is, I presume, less of a problem.

My guess is that the Dome is more of a guide to what will happen to London’s Olympic stuff. There was much faffing about in the immediate aftermath of the Millenium, but eventually, a meaningful use was found for it. Likewise, London Olympic remains will either be used or done away with and built over.

Meanwhile here are a couple more Olympic snaps I took recently. Both are of the Olympic rings now hanging from Tower Bridge. First, before they were swung down into place:

And second, after:

For further fun, you can enjoy a recent Chinese homage to Tower Bridge. It’s twice as good as the original, because it has twice the original number of towers!

Enough diagnosis. What is the cure? A change of personnel will not do it. The search for chief executives who are not motivated by greed and for regulators who are sufficiently god-like to know how to design rules that cannot be gamed will never succeed. The truth is, the financial system, like the whole of human society, was not designed in the first place; it evolved. And the answer is to allow a better one to evolve.

– Matt Ridley

Do not grip fireworks with your buttocks.

– The final entry in David Thompson’s most recent batch of Friday Ephemera, with a link to the video that will convince you of the wisdom of this advice, in the unlikely event that you are not convinced of this already.

Last night I watched a television documentary about the career and achievements of Gordon Murray, a very different Murray from the tennis Murray whom I mentioned here on Saturday. Gordon Murray designs cars.

He started out doing racing cars. Time was when Gordon Murray was applying his extraordinary ingenuity to designing such things as “improvements” to McLaren racing cars, improvements whose only rationale was that they drove through some silly loophole in the rules of Formula 1 racing, a loophole that would soon close and render the new design feature utterly pointless. Okay, F1 is fun, and okay, most of what Murray did was make F1 cars go ever faster and get ever cleverer. But that rule-dodging bit in particular seemed like a serious waste of a talent, and I am sure the television people intended it to.

But Gordon Murray then took a big step towards applying his stellar engineering skills to a task more worthy of them when he designed the McLaren F1, which is the fastest car that multi-millionaires can buy to drive on regular roads. Better.

And now, Murray has designed a small car. This small car looks like a superior version of one of those covered over motorbikes, but actually it is a lot cleverer and more capacious than that. It is cleverer because it embodies half a lifetime of Murray’s experience in Formula 1, making everything in cars lighter, smaller and just plain better.

There are many ways to innovate. A good way is to innovate in just one aspect of a design, while relying on tried and tested technology for everything else. That way there is only one thing to go wrong and to get right. Very wise.

But Gordon Murray’s way is different. More “courageous”, you might say. He looks at everything. He looked at small cars the way huge teams of aircraft designers are perpetually looking at aircraft design, chiselling little ounces of bulk from here, there and everywhere, and where possible trying more serious rethinkings and rearrangements, adding up to a seriously improved product.

Innovation done this way can unleash a ton of mistakes, with all the good ideas getting overwhelmed by a few bad ones. Everything has to work. You have to get, near enough, a hundred out of a hundred, or you fail. You need lots of skill and experience to get a score like that. Gordon Murray, it would seem, has an abundance of both.

In particular, just as a for instance, this small car is interesting (courageous?) in using the same seating arrangement as the McLaren F1. In the McLaren F1, instead of the driver sitting on one side at the front, and then another bunch of people sitting behind on another big seat, or not, the F1 has the driver in the front in the middle, and two other seats on either side, but set back, in an arrow formation. The passengers can presumably stretch out their legs beside the driver’s bum. And the new small car has just the same seating set-up. Which makes it feel bigger inside than a regular small car, but much less bulky from outside.

Also, the doors to the new small car are an all-in-one door, which opens up and forward, like the top of an airplane. Combined with that seating arrangement, this makes it easier to get in and out of than the competition.

This small car comes in two versions. There is the black T25, which is petrol driven, and which looks like this:

And there is the blue version, the T27, which runs on electricity. They showed the T27 towards the end of the television show, in the company of some veteran cars in a place that looked a lot like central London, and I thought: hang on, this rings a bell. Sure enough, after a little digging in my photo-archives, I found this snap:

I took that picture of the T27 on the same day, early last November, that I took all these photos of veteran cars in Regent Street. (There is a slice of veteran car there on the right.) I far prefer the look of the black T25. Its strangely retro styling reminds me of a delivery van of the sort I recall from my youth. The blue T27 looks to me, still, like a boring little car only pretending not to be boring, which is why I had no idea how interesting it was when I first set my eyes and my camera on it. Oh me of little faith. Kudos to me, though, for taking “too many” pictures whenever I go out a-snapping. Time and again, as in this case, I only realise later, and sometimes a lot later, what I photoed.

Being so unbulky, this new T25/27 is much more fuel efficient than regular small cars, but its energy efficiency does not stop there. One of the most interesting moments in the programme came when they talked about how this new car will be made. There is more to cars being efficient than cars being efficient to drive. They also have to be as efficient and as cheap and as easy as possible to make, and this new car requires far less in the way of capital investment before you can start cranking them out. The huge manufacturing costs of regular automobiles, said my television, explained why most car makers prefer making expensive cars to cheap cars. Cheap cars don’t make any money. But this cheap car will make money for those who make it, or that’s the idea. That’s another huge potential step forward.

The claim was repeatedly made in this programme that this T25/27 is the biggest innovation in car making since the Model T, what with the revolutionary way that the Model T was manufactured. But the cars that this new gizmo makes me think of are the Citroen 2CV and the Volkswagen, which were likewise designed to be more easy to make than regular cars, were they not? The Citroen 2CV, I seem to recall reading, was banged out by peasants in a big barn, or some such thing, just after WW2, when manufacturing skills were scarce. This seems a lot like the T25/27 plan, which is a twenty first century version (i.e. with shipped in magic bits) of the same thing.

The T25/27 secret, apparently, is that the structural frame of the car is made of metal tubing, and that is far easier for cheapo, Third World type fabricators to work with than however small cars are made now, by the likes of Toyota and Ford and the rest of them.

The upshot of all this is that here is a small car, a truly small car, that will make regular non-multi-millionaire motoring massively less of an energy gobbler.

Which in fact means, if it all goes to plan, that many more people will drive around in such cars than drive around in any cars now, and the total amount of energy consumed by these cars as they wizz hither and thither will then go up. But, a lot more people will be having fun and getting themselves and their stuff from A to B. So: very good.

Or, it could be that too many of Gordon Murray’s innovations will turn out to be mistakes, in which case car historians may point back to the T25/27, to say where Toyota and Ford got their next bunch of ideas, while the rest of us may soon forget this most interesting and admirable man. What if, for example, we regular punters just can’t be doing with that strange new seating arrangement? What if drivers just have to have company sitting right next to them when driving? And what if that radically rethought manufacturing method turns out to have too many mistakes built into it? So maybe the T25/27 will go down in car history as an heroic failure, rather than getting flagged up as a triumph, Volkswagen or Deux Chevaux style. It may be remembered, that is to say, as a very gutsy shot at a real car that was actually only a concept car. We shall see.

Earlier yesterday, in the afternoon, I caught Jenson Button and Lewis Hamilton moaning on the telly about their (McLaren) racing cars had been way off the pace in the British Grand Prix. Are they missing Gordon Murray, I wonder?

Right about now, Henry IV Part 1 was supposed to start on BBC2 television, and I had my TV hard disc timed to gobble it all up. But luckily, I did not actually go out, and have thus been able to learn that Henry IV Part 1 has been postponed, until such time as the Wimbledon Men’s Doubles Final reaches its conclusion. Final set, and a Danish bloke and – get this – an English bloke – are leading 4-2. This is not a movie. This is the real thing. Even weirder, the English bloke reads like a spelling mistake. He’s called Johnny Marray. Like all of England that ever pays any attention to tennis, I am saying, who is he? And: how about that for a funny name, just one letter away from the Scottish bloke. Marray is now serving. For the match. 0-15. Pity the poor commentators.

Tomorrow, that same Scottish bloke, Andy Murray, has the seemingly hopeless task of defeating the titanic Roger Federer, in the Men’s Final.

15 all.

30-15.

Strange how the long awaited Great Hope of British tennis is now, following years of Henmaniacal disappointment, Scottish. For Andy Murray is indeed the first Brit to get to the Wimbledon Final, apart from Paul Bettany, since King James 1 lost in four sets in 1607.

30 all. 40-30. Match point.

I’m kidding, but the last British finalist was called “Bunny”, and he lost his final long before most of us around here were born. He was a shorts pioneer, apparently. Blog and learn.

In 1932 he decided that the traditional tennis attire, cricket flannels, weighed him down too much. He suffered from jaundice and was handicapped by the weight of his sweat-soaked long trousers in hot weather.

“They’ve done it!” So. One down. One to go? For a Brit like me, tomorrow is a win win. If Murray follows Marray’s example and wins against Federer, hurrah! If he loses, then it’s: Oh yes, that was when Scottish Murray lost and English Marray won. For a Scotsman, imagine the horror if Murray loses, as I fear he will. Already, I imagine they are cursing Marray for pissing in their soup.

In extreme contrast, the Scots seem entirely to have lost the knack of playing football. Like all English people who have not been actively and successfully dodging the news, I know that England won the World Cup in 1966. (I remember it well. I watched it live on television, in Finland, while on a bicycle trip.) But what I also remember is that in, I think, about 1967 (yes), Scotland famously beat England at football, and it was that same World Cup winning side that they defeated. Names like Denis Law and Jim Baxter are still remembered, and not only in Scotland. Only weeks after that, Glasgow Celtic became the first British club to win the European Cup, the direct precursor of the the current European Championship. And remember that this was the time when if the name of the club was “Glasgow” Celtic, that meant that most of the people in the team were, if not actually from Glasgow, at least from very close to it. Which is not how it is now at all. (Scroll down to the bottom there to see the names of the Chelsea team who beat Bayern Munich in the final of the Euro Cup this year.)

Man U (also featuring Dennis Law, I seem to recall) won the European Cup a year later, but it was Celtic that won it first.

But now, look at the Great Britain Olympic soccer team. Not one Scotsman in it. And no matter how many foreigners they have in their teams now, neither Celtic nor Rangers seem ever to get far in the Euro Cup these days.

Henry 4/1 will now start at 10pm, exactly one hour later than advertised.

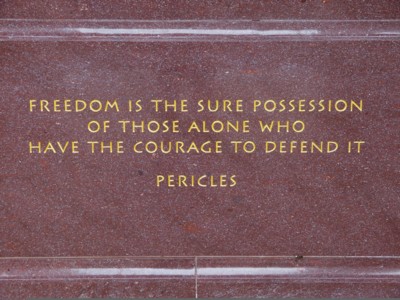

This inscription is carved onto the Memorial to those who died serving in Bomber Command during World War II.

The memorial was unveiled by the Queen just under a week ago, on June 28th. It is at Hyde Park Corner, in London, at the western end of Green Park. I photographed it this afternoon.

I live close to one of the great old cities of Britain, Newcastle upon Tyne. In two centuries it has been transformed from a hive of enterprise and local pride, based on locally generated and controlled capital and local mutual institutions of community, into the satrapy of an all-powerful state, its industries controlled from London or abroad (thanks to the collectivization of people’s savings through tax relief for pension funds), and its government an impersonal series of agencies staffed by rotating officials from elsewhere whose main job is to secure grants from London. Such local democracy as remains is itself based entirely on power, not trust. In two centuries the great traditions of trust, mutuality and reciprocity on which such cities were based have been all but destroyed – by governments of both stripes. They took centuries to build. The Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle, in whose magnificent library I researched some of this book, is but a reminder of the days when the great inventors and thinkers of the region, almost all of them self-made men, were its ambitious luminaries. The city is now notorious for shattered, impersonal neighbourhoods where violence and robbery are so commonplace that enterprise is impossible. Materially, everybody in the city is better off than a century ago, but that is the result of new technology, not government. Socially, the deterioration is marked. Hobbes lives, and I blame too much government, not too little.

– A paragraph near the end (pp. 264-5) of The Origins of Virtue by Matt Ridley. Time was when the best popularisers of science were left wingers, and they bolted left wing conclusions onto the end of their popularisations. Ridley does a similar thing there, but in the service of capitalism, progress and freedom.

Ridley is a terrific writer, and there are dozens of quotes scattered through this book which I could have chosen for the SQotD treatment.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|