We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

On the last Friday of May, May 31, the Friday coming up, which happens also to be the last day of May, the speaker at my regular Last-Friday-of-the-Month meeting at my home will be Aiden Gregg.

I bumped into Aiden Gregg at another talk we both attended at the Institute of Economic Affairs, and quickly discovered two things about him. He is an academic psychologist, to be more specific: a lecturer at Southampton University. And, he is a straight-down-the-line, uncompromising libertarian. Those two facts alone were enough to get me inviting him to give a talk at my place. Libertarian economists are, if not two a penny, at least quite numerous, hence the existence of such institutions as the Institute of Economic Affairs. But libertarians in other academic specialities are much rarer, and we must, I think, do everything we can to encourage and make much of such people.

Just being a libertarian, and mingling and continuing to mingle with the kind of academics who are just about never libertarians and who in many cases have no idea that such a thing even exists, is itself something of an achievement. Even if you say very little about your libertarianism, and perhaps especially if you say very little, this can have all kinds of consequences. One particular consequence is that knowledge of what academic psychology typically consists of will be drawn into the libertarian movement. They may not learn much about our opinions, but we are far more likely to learn about theirs. As the late Chris Tame used to say, we need our people everywhere. And by that he meant especially everywhere in academia.

So, my attitude to Aiden Gregg is: well done mate, for just being what you are, never mind whatever else you might manage to do for the cause of liberty by actually saying stuff to your academic colleagues, and publishing things.

In that spirit of admiration, I said to Aiden Gregg, just talk about whatever you want to talk about.

Here is the email he sent me in which he said what he will be talking about:

The title of my talk will be “Sax and Violence”. “Sax” is not a typo but a contraction of “sex and “tax”!

In the talk I shall argue that, ethically speaking, the proactive seizure of one’s body and property by others, including for the greater social good, are analogous at an fundamental level.

According, it is either the case that both are generally legitimate, or that neither are generally legitimate, but not the case that one is generally legitimate but the other is not.

In Western cultures, however, the proactive seizure of a portion of someone’s property (or income, its monetary representation), for the purposes of enriching some while impoverishing others, if democratically elected rulers so dictate, is readily accepted by most democratic voters, and is seen not only as permissible, but also as obligatory, or at all events, regrettably necessary.

In contrast, in the same cultures (though not others), the proactive seizure of a portion of someone’s body, for the purposes of sexually satisfying some while sexually dissatisfying others, if democratically elected rulers so dictate, is firmly rejected by most democratic voters, and is seen as not only forbidden, but also as repugnant, and in any case, wholly unnecessary.

If, ethically speaking, it is not the case that one is legitimate but the other is not – and I shall attempt to rebut several key objections – then the acceptance of the first, but the rejection of the second, is an ethical bias stands in need of explanation.

One theoretical approach to accounting for such a bias would be system justification theory, developed by left-liberal thinkers to explain the persistence of social hierarchy, but arguably even better suited to explaining the perceived legitimacy of statist authority.

So, the talk will feature some ethics and some psychology.

So, this will be a talk that is in several ways outside the usual libertarian boxes, both in terms of who is giving it, and what it will be about. Good.

If this or any other of these meetings are of interest to you, and you aren’t already on my email list, get on it by emailing me. Click where it says “Contact”, top left, here.

And I also (see below) recommend this video. I won’t describe it at length. Suffice it to say, as David Thompson does say, that you need to watch it right to the bitter end. DT found it here, where viewers were also urged not to miss the end.

An early DT commenter declared that he saw how things would end right away, but I didn’t.

I recommend this report by Danny Weston (guest writing at Bishop Hill) of a talk at the London School of Economics given by NASA’s James Hansen. Hansen is a manic climate alarmist, and the audience was almost entirely other manic climate alarmists. But Weston himself managed to get a question in edgeways.

To echo many of the Bishop Hill commenters, congratulations to Danny Weston for attending this event, for spoiling the party by actually expressing doubts out loud about what Hansen said, and above all for writing his report of the event, for an influential climate skeptic blog.

Opponents, however manic, need to be listened to, and argued against. The point is often made here by commenters that arguing against such people as Hansen and this LSE audience is a waste of time and effort, and there is a definite and entirely understandable trace of this feeling in Weston’s own report. Wrong, wrong, wrong. In among that audience were other doubters besides Weston, a few of whom identified themselves to Weston afterwards sotto voce, congratulating him for what he said. Genuine undecideds, and even some of the majority who flatly disagreed with Weston, may also have been impressed by Weston’s sheer guts, as well as by his arguments. And by writing it all up, Weston greatly reinforces this silent bystander effect.

Weston ends his report with these words:

All in all a thoroughly depressing experience.

I hope that responses like this, and like the many other positive comments at Bishop Hill likewise full of congratulation and admiration, will have cheered Weston up a bit, and maybe even a lot.

Everyone in America who cares knows that President Obama has for years been encouraging his supporters within the governmental machine to use their governmental powers to harass his political opponents. You have to be deaf, dumb, blind, and living a lot further away from America than I do, not to have known about this for a long time. When it comes to IRS harassment of those he objects to, President Obama has been behaving absolutely as transparently as he promised he would.

To talk now of a “smoking gun” is like witnessing the Battle of Waterloo and saying: “Hah! A smoking gun! Over there!” True, but daft.

A serious defence of President Obama in this matter, from him or from anyone else, cannot be based on the claim that he has not been behaving as he has been behaving. The serious argument is about whether it matters how he has been behaving, and if it does matter, whether it is a good or a bad thing. To defend Obama, as his wiser supporters already realise, must mean defending what he has quite obviously and publicly been doing.

Which might well work, because it is also clear that a great many Americans do agree with what President Obama has been doing. They want big government, and they want the big government they already have to silence anyone who doesn’t want big government.

It’s not possible to prevent people, particularly people whose goal is power, from abusing it. All we can do is deprive them of it.

– This comes near the end of a very good piece by Rand Simberg about the IRS, what it did, why, and what to do about it.

Which is what our own Jonathan Pearce also said recently.

The End of the World Club (there seem to be quite a few – can’t find a link to the one I mean) is a bunch of Austrianist-inclined people who meet at London’s Institute of Economic Affairs every few weeks to talk about the state of the world, and than afterwards maybe drink and/or dine locally, to try to cheer themselves up again.

Simon Rose, the guy who runs the End of the World Club, has asked me to kick off the discussion on the evening of May 28th. The following is a hastily typed summary of what I have in mind to suggest that we all talk about. I emphasise the “hasty” bit. Under comment pressure I will surely want to modify or even abandon quite a few bits of what follows. My number one purpose here is not to be unchallengeably right about everything, although you never know your luck; my number one purpose is to provoke thought and talk, by looking at the world from a slightly different angle to the usual angles. It began as a mere email to Simon Rose, but as you can see, it got a bit out of hand. My email to Rose will now be the link to this.

Since it’s the “End of the World” Club, I thought it might make sense to think about optimism and pessimism. Is that title (“End of the World”) for real? Or is it playfully ironic? How optimistic or pessimistic are we End-of-the-Worlders about the near future, and the longer term future? How optimistic or pessimistic about the near and longer term future are our statist adversaries? How much difference does that make to anything?

In recent decades, it has been the Austrian School who have been most rationally and persuasively pessimistic about the short run (by which I mean the next few years and the next, say, couple of decades). And it has been the politically middle-of-the-road statists who have been most unthinkingly optimistic, first, that no sort of economic catastrophe was coming, and now, when they try to be as optimistic as they can about the catastrophe (that has happened despite their earlier unthinking optimism) not getting any worse. Austrianists, in contrast, regard the present turmoil as proof that they were and remain right about everything, and that their pessimism, now, about the short term (and actually not that short term) future will accordingly also be entirely justified. Austrianists are mostly pessimists now. (Think Detlev Schlichter.) But they are optimistic about their own thought processes, in which they have absolute confidence.

But when it comes to the bigger picture, it is the broader free marketeer tendency who are now the optimists.

Socialists used to be optimistic, about how their socialism would make humanity materially better off. They were only pessimistic in the sense that they feared that they might never be allowed to do socialism. But about half way through the twentieth century, socialists stopped saying that they would do affluence better than capitalism was doing it, because the claim that capitalism wasn’t doing affluence was becoming absurd. Instead they turned against affluence.

They became economic pessimists about their own policies, in other words. But they stuck with their policies and turned their backs on the idea of mass affluence being a good thing. The Green Movement, which is what socialism has mutated into, is a huge surrender on the economic policy front, and an attempt to engage with the world on a quite different front. Socialists have surrendered the happy future. You have to listen a bit carefully to hear this. It took the form of a huge change of subject, from making the future happier, to making it more virtuous and poverty-stricken. They used to like affluence. Now they trash it. (Have a listen, for instance, to this excellent Jeffrey Tucker talk.) They used to be leading us towards an imaginary heaven on earth. Now they claim merely to be saving us from an equally imaginary hell on earth (and thereby are actually trying to create a real one). I am optimistic that this imagined hell on earth is also now on the way to being abandoned (see, e.g., this blog posting by Pointman). (What will be their next Big Tyranny Excuse?)

Meanwhile, classical liberals (as opposed to the illiberal liberals of our own time) note how free market ideas have raised humanity from abject poverty to a standard of living that was formerly unimaginable even for kings and emperors. Some free marketeers are rationally optimistic (to echo Matt Ridley‘s recent book title) that life will continue to get better, despite everything the statists and socialists now try to throw at it. Other free marketeers are now supremely optimistic that free market policies will work superbly, provided those policies are followed. Think J. P. Floru (an earlier speaker to the End of the World Club – very eloquent, very confident, I was there). Conditional optimism, you might call this. This is the same optimism that the socialists had a hundred years ago or so. It is very potent. The future will be wonderful, but only if you join our cause and help us save this wonderful future from being trashed by our malevolent, idiotic adversaries.

In the first half of the twentieth century free marketeers were much more tentative and intellectually timid. They often agreed that material progress would only happen if big government (with or even without big business) made the running, but argued for freedom anyway, as something that should be sentimentally preserved despite its economic cost. No wonder they did so badly.

But free marketeers are now the optimists. In the long run this means we will win. Discuss. See also: optimism (even irrational optimism) as a technique for success, individually and collectively. See also: pessimism (even (especially?) rational pessimism) as a recipe for failure, individual and collective.

That is pretty much it, and is surely more than enough to keep us talking for however long is required. Email me (you surely know how by now) if the End of the World Club is of interest, and I’ll pass it on.

David Cameron’s position is that he is trying to persuade the Golf Club to play tennis, but that if they refuse, he will continue to play golf.

– Michael Forsyth, on Daily Politics today, describing the posture of the Prime Minister with regard to the European Union.

“Dear incompetent ninny …” No. “Dear complete imbecile …” I suppose not. “Dear feeble-minded simpleton …” I’d better not. Well, fine, then. “Dear State Representative …”

– Here via here. (I must declare an interest however. Another of the quotes in that second “here” was from here.)

This is actually quite profound. We are often tempted to get angry with state functionaries. But since we are usually begging things from them, rather than demanding them in the manner of one who could take his business elsewhere – with the state there is no elsewhere, we usually choose to remain polite. And if we finally get what we are begging for, we tend to be effusive in our thanks, if only because so pleased that the ninny did something less than completely ninny-ish. The result is a world in which state functionaries genuinely imagine themselves to be loved by almost all of their victims and hated by hardly any of them.

Incoming from Rob Fisher (to whom I owe him a blog posting about this talk that he gave at my home a while back – short version: it was very good):

Finally I found a video that explains to my satisfaction what using Google Glass is like. It’s a display that you wear, that uses clever optics to give the appearance of looking at a 25 inch screen 8 feet away.

Parts of this video are welcome-to-the-future moments.

By the way, these voice commands already work on your phone; tap the microphone symbol top right and say something like “wake me up at 8am”.

My phone being the Google Nexus 4 that I have been going on about lately, for example in the previous posting here.

I won’t be watching this video in the immediately immediate future as I have other things to be getting on with. But I definitely will very soon.

What Rob says about voice commands is interesting, I think. I have long suspected that a big computer leap would occur when we stopped communicating with computers by typing on them, and instead just talked to them. “Jeeves, what’s that thingy where the thingamajig I was talking about yesterday is yellow instead of black?” “Do you perhaps mean this, sir?” “Yes, that’s the thing. You’re a genius Jeeves!” “One does one’s best sir.” Etc.

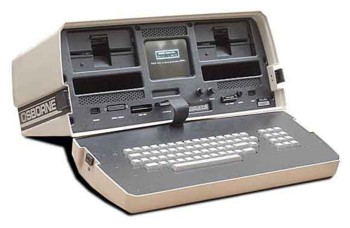

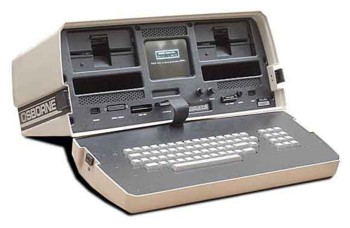

From time to time I do Samizdata postings about how rapidly technology is advancing these days. Recently I stuck up an SQotD on the subject. Here is another such posting. Basically it’s two pictures.

The first is a picture of my first proper computer (I do not count the Sinclair Spectrum), purchased in about … 1981? This computer, an Osborne 1, consisted of a very small screen, a keyboard, and about half a ton of electrical gubbins, including two disk drives, each accommodating disks that were, I seem to recall, 256kb in capacity. 256kb was a lot of kb in those days.

The second picture is of my latest computer, which is a Google Nexus 4, plus a couple of bits of plastic to prop up the Google Nexus 4, plus a keyboard:

For me, the killer app of all computers has always been word processing, the ability to type a piece of writing into a machine, and then to modify and expand the piece at will, and only when it’s nearly finished have it automatically printed out. And then printed out again if you need that, as you almost certainly will. Amazing. (This being the twenty first century, you may want to read “print out” as “publish”.)

My first “word processor” (the inverted commas because word processing as we now use that phrase was exactly what it couldn’t do), which I used for about a decade, was an Olivetti typewriter. For this I paid twenty five quid, which is about the same as what I recently paid for the Google Nexus 4 after you include inflation. For those who do not know what a “typewriter” is, the basic rule was that the only way you could store the words you had thought of, in the order you wanted them in, was to print them all out, one letter at a time, as you thought of them. The switch from that to the Osborne 1 remains the single most exciting technological leap of my life, although the arrival of blogs runs this a close second.

As for the smallness of the screens of both these computers, well, each to his own, and I entirely get why many would hate to process words on such a tiny thing as the Google Nexus 4 or with a screen as tiny as that of the Osborne 1. But I loved the small Osborne screen. There was something very appealing to me about those tiny little letters, so much more so than the big clunky letters on other computers of that era. Me being short-sighted, the distinction that really matters to me is not big-screen-versus-small-screen; it is screen (however big) far away: bad, versus screen (however small) near: good. And if the Osborne was not in any very meaningful way “portable”, it was at least, to use a word from those days, “luggable”, from one work top to another, as and when the need arose, which for me, then, it often did.

And just as I loved the tiny old Osborne screen, I now rather like the Google Nexus 4 screen. But of course what I really like about the Google Nexus 4 screen is that, since a tiny screen is all that it is, it is so light and so small that I am happy to carry it around in case I need it to process any words, even if I never actually do, on that particular expedition. For me, in my present aging and physically weakened state, the difference between a computer too heavy to carry around without being irritated by it unless I use it, and a computer so light that its weight is not a problem even if I don’t touch it all day long, is a big difference. Even today’s small laptops – minute compared to the Osborne – fail this test, for me, now.

The beginnings of this posting were mostly typed into the second of the two computers pictured above, before being transferred into my regular non-portable computer, the one that resides permanently in my kitchen. I am still amazed at how well this transfer worked, the very first time I tried it. While I was doing the transfer, it looked as if all the paragraphing would be lost, but when I pasted everything into a text file on the kitchen computer, there it all was, just as it began. Magic.

In addition to being a word processor, the Google Nexus 4 is also, as already noted, a telephone. And like all mobile telephones these days, it can also send what used to be called telegrams. It is also an A-Z Guide to London, and a map of the Underground. The map even works, unlike an A-Z of London, when I venture outside of London. It tells me when the London bus I await will reach me. It is a mini web-browser, a mini-Kindle, and a means of posting relatively straightforward postings to my blog or (when I have worked that out) to this blog. It is a gadget for identifying music recordings just by it listening to them, being just as good at identifying classical recordings as it is a identifying pop. It is even a rudimentary camera. All of which makes it that much more likely that I will use my Google Nexus 4 for something during just about every expedition I go on. The old Osborne 1 could do none of these things. But you knew all that, and much else besides which I have yet to discover. You get the pictures.

I am, of course, not the only one who has noticed how well technology is doing these days compared to politics. If you look for this particular meme, you see it everywhere. Here is a whole book with that notion as its starting point, linked to recently by Instapundit. (Who, by the way, also linked to and recycled that SQotD. I thought he might like that one.) Says the author of this book, Kevin Williamson:

Why are smart phones so smart – getting better and cheaper every year – while our government is so dumb? Is there a way to apply the creative and productive institutions that produced the iPhone to education, public schools, or Medicare?

He thinks there is, as do I. More from and about Williamson here.

LATER: Instapundit quotes Williamson again:

We treat technological progress as though it were a natural process, and we speak of Moore’s law — computers’ processing power doubles every two years — as though it were one of the laws of thermodynamics. But it is not an inevitable, natural process. It is the outcome of a particular social order.

A week ago, a friend of mine, a retired journalist now living in France, stayed with me for a couple of nights, kipping down on my living room sofa-bed. He arrived on Sunday, and on Monday he journeyed forth at midday, to have lunch, with a big gaggle of his old journo pals. The lunch was quite liquid and very prolonged. Although I should add that when he got back to my place around midnight he behaved impeccably, his only slight infringement of good manners being a tendency toward repetition.

All of which got me a-googling the phenomenon of Lunchtime O’Booze, that being the soubriquet that was bestowed upon journalists of a certain vintage by Private Eye. The words explain themselves.

This caused me to encounter some bang-up-to-date observations about the Lunchtime O’Booze generation of journos, and the disdain with which they are now often treated, in a piece entitled In Defence of Lunchtime O’Booze, by John Dale.

In characteristic journo style (from which I dare say I could learn) Dale gets straight to his point:

Alcohol is a truth drug. Reporters use it as the weapon of choice to breach the carapace of lies erected by prime ministers, politicians, police and anyone else tempted to become tinpot Hitlers.

With drink you don’t hack with a keyboard. You hack with the clink of a glass and then download your personal malware and intellectual trojans directly into someone else’s brain.

Occasionally you get inside their heart as well, which is a cruel bonus. Alcohol, when applied by good reporters, brings the powerful and the pompous crashing to earth, face down in the gutter right in front of the paps shooting for posterity at 40 frames a second.

Next morning the prototype tyrant wakes up a nicer, gentler human being. …

And now for the bang-up-to-date bit:

… So, for me, the most alarming feature of the Leveson Inquiry was that it turned anti-alcohol, as if coveting the pulpit at a temperance meeting.

Any moment I expected Leveson to raise a placard saying: ‘Lips that touch liquor shall never touch mine.’

Leveson’s point is that the Police should beware getting too pally with journos, and especially of drinking with them too much. But Dale’s point is that although the Police would be wise to shun alcohol, journos who do the same are missing a big trick. Journos taking it in turns to tell Leveson that they abjure the demon drink should instead, says Dale, be willing to stand up, as best they can, and defend alcohol as a vital tool of their trade.

Dale follows with a character sketch of one Noel Botham, with a photo of Botham holding a drink and involving a drink-lubricated interview:

He raises his glass, giving it a tilt as if it were a journalistic rapier. …

A youthful 72, Botham is relevant because he is a lifelong bon viveur who has used his taste for the high life to pursue a form of free-range journalism which is the antithesis of that promoted by most Leveson witnesses, the reborn PCC and various journo professors. He’s the last cavalier in a world of roundheads. He symbolises free range against the battery farms of Canary Wharf and other media plantations.

But drink has not now stopped working its truthful magic, despite what Dale says. Botham is not actually the “last cavalier” by any means.

Guido Fawkes is often talked about as a challenge to traditional journalism. But when it comes to drinking and as a result learning stuff, Guido is no challenge to regular journalistic ways. He is booze and business as usual.

If you want to introduce someone to libertarian thinking, encourage them to try this experiment. Spend a few days reading nothing but technology news. Then spend a few days reading nothing but political news. For the first few days they’ll see an exciting world of innovation and creativity where everything is getting better all the time. In the second period they’ll see a miserable world of cynicism and treachery where everything is falling apart. Then ask them to explain the difference.

– Andrew Zalotocky, commenting on this, here, about #HackedOff, many weeks ago.

I had this all ready to be an SQotD right after it first got said, but then another SQotD happened, and I forgot about it. Today, I chanced upon it again.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|