We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

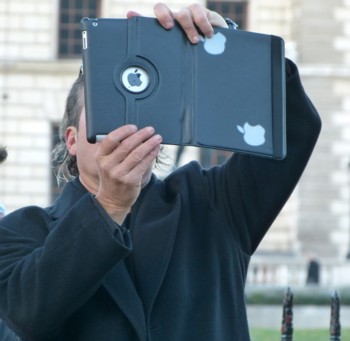

As noted in my previous posting last night, I went out photoing photoers last Sunday, and one of the more interesting photoers I photoed was this guy:

That’s an iPad, being used as a camera. I mentioned this to Michael Jennings, and he told me that the first iPad didn’t have a camera built in. The second one did, but it wasn’t very good. Not designed for proper photoing, merely for video-conferencing. But people used it to take proper photos anyway, or they tried to. And on iPad number three, the camera is quite good. Not in the same league as a dedicated camera, but good enough for many, for taking tourist snaps in good daylight and for telling friends what they are seeing.

I know the feeling. If you are a techy, or if whatever you are doing just has to be really, really good, you use the best kit for each job that you are doing. But if you are a civilian, you just love the idea of one machine that does everything for you. There is just one pile of magic to master, just the one gadget to be faffing about with when you are on holiday. I have never used an iPad, but I entirely know why this guy is using his iPad to take photos, rather than a regular camera type camera.

I talked with him. So, using one of those things to take photos, eh? Yes, he said, and he eagerly showed me some of the photos he had just taken, of Westminster Abbey. They looked fine to me, although a regular CSI character could easily work out the man’s identity from his reflected face in this:

He’s not the first iPad (or Tablet or whatever) photoer I have spotted in recent months, just the first who obliged with a good clear pose for me to photo, a pose which obligingly hid his face.

I have been photoing digital photoers for over a decade, and if there is a technological trend in evidence, it is that the range of cameras being used by digital photoers has slowly grown. First, there were the very first digital cameras, like my very first digital camera. Rather big, very expensive and rather clunky, but they worked! Meanwhile the Real Photographers were going digital, with even bigger and massively more expensive cameras, which looked, then as now, just like regular old cameras that used film, and which made use of the same even more expensive sets of interchangeable lenses. Then cameras started to emerge which were betwixt and between (“bridge” cameras) the little ones and the Real Photographer cameras, like my last two cameras, with their ever more amazing zooming abilities. I try to get cameras in focus whenever I can, and in my photos you can see the zoom numbers climbing as the years have gone by, the latest Canon “bridge” camera being 50x!

And while all that was happening, mobile phones were also getting good enough to use as cameras. Just like my iPad Man, Mobile Phoner relishes only having one machine to fret about, to do everything. Hence the ever increasing smartness of smartphones.

It all reminds me of how General Motors worked out, in the 1920s, that the idea of just one basic kind of car for everyone was silly. Instead GM offered a range of cars, to suit all tastes and pockets. But, there never was a Model T digital camera, available only in black, and the camera market is easier to enter, so there never was a General Cameras either. The range rule has prevailed with digital cameras from the start. It didn’t have to be thought of, it just happened.

This range of cameras is reflected in my latest clutch of photoer photos, here (already linked to above). There is the Real Photographer (1.2), or at any rate the photographer using a Real Photographer camera, the guy with the reflecting sunglasses. There are the ever smaller and ever cheaper dedicated digital cameras, often decked out in bright colours (silver (2.3) and red (3.1) in these photos as well as just black). There is the guy using his smartphone (3.3) to take photos (of the man blowing bubbles on the South Bank). There is the 26x zoom camera (3.2). Even the little red camera (3.1) is 10x, as you can clearly read if you click on that one. Tellingly, there are cameras there where it is a bit hard to tell at a glance if they are single fixed-lens or multiple choice lens, bridge or Real.

There must also be another kind of camera being used, to add to all these others, which is the one that is so small and so unobtrusive that it cannot even be seen. These cameras are hidden in glasses, or in buttons, or in hats, or in jewellery. Time was when only the likes of James Bond had such devices, but now, I presume, anyone who wants such a camera can have one. I must have photoed many such cameras, but I will never know about it.

I salute these invisible cameras with particular fervour. They are Little Brother’s answer to Big Brother’s now ubiquitous and very visible surveillance cameras. These invisible cameras are the reason that They will find it so very hard to ban outdoor photography by civilians, however much They might like to and however hard They try, because They won’t be able to see it happening and tell it to stop.

Face recognition is now starting to loom large, and it won’t be long before etiquette changes in response. The internet has been instructed to email me whenever face recognition gets a big mention, and the emails ever since I said to do this have flowed to me in a steady trickle. Face recognition will soon be a Big Issue, and for many it already is. To photo anyone in public will soon be universally understood as like a potential public announcement of exactly where they were, exactly when. I presume that celebrities of ever decreasing celebrity are already hunted down with such software. Now regular people are starting to track each other. Soon, this possibility will be routine. Governments will want to make it illegal for anyone except themselves to behave like this, but I can’t see how they will be able make this stick.

I wonder where my husband was last weekend. I know where he said he was, but … let’s run the programme, and see if anything shows up. Was he in London with that tramp with the pink hat, I wonder?

That young speaker I heard yesterday for the first time seemed like quite a dangerously clever chap, with a potential big future that I disapprove of. So, www, show me every picture you have, and I don’t just mean the ones with his name attached. What does he do with himself? How does he relax? How does he unwind? Give me some dirt.

That kind of thing.

As the memory of the internet grows, people will be living more and more of their lives in a state of perpetual surveillance, of everyone, by everyone. At present, your name needs to be spelt out and attached to such revelations for them to be revelations. But that is fast changing. Soon, your face will be enough.

When I say “soon”, I don’t really know when all this is going to happen, and be seen to have happened. This may already be happening, or it may only really get talked about a decade hence. But happen it surely will. Whereas I only arrange to be informed when the words “face recognition” appear in an internet news story, it is surely only a matter of time before we can all of us say “show me any picture that looks like this person”. → Continue reading: What happens when face recognition becomes the new reality

Yesterday, as earlier reported, I attended an event about road pricing. It was typical IEA. Men in suits and ties with irreconcilable beliefs took it in turns to be irreconcilably polite about everything, while other men in suits and ties listened with equal politeness:

There are some of the men in suits and ties waiting their turn to be polite. And look, one man in a suit and a tie is even straightening his tie, James Bond style, although there the resemblance ends. That’s Oliver Knipping, co-author, together with Richard Wellings (the man in a suit and a tie on the right whose face is blocked out by the video camera) of a recent IEA publication entitled Which Road Ahead – Government or Market? Do you see what they did there? Which road, as in policy, metaphorically speaking, for dealing with roads, as in roads, literally.

I am being much too rude. It was actually pretty interesting if you like that sort of thing, which I only somewhat do, hence my rudeness. I went because I knew that although I would be rather bored during the event, I would afterwards be glad that I had attended, and so it has proved. I got a copy of Which Road Ahead for only a fiver, and better yet, I met a man with a blog, called Road Pricing.

I like road pricing, for the same reasons I think that governments shouldn’t give away train tickets to everyone just because the train system is government owned and/or government controlled and people have already paid for it that way. What if some people don’t like trains and never use them? It’s not fair. Without journey pricing, the trains will get even more impossibly crowded. Privacy? That argument was won and lost when they introduced number plates, I reckon. A man called Gabriel Roth was quoted as saying that the road systems of the world are the last bastions of Soviet style central planning. Which isn’t true. What about central banking? But I like the sentiment. This is a product for which people queue for the product on top of the product thereby destroying the product. That can’t be the right road ahead, now can it?

Scott Wilson, the Road Pricing blogger, agrees. But you won’t read many arguments at his blog about why road pricing is good. What you will read is reports about how road pricing is being done in various parts of the world, well or badly, and criticisms of places where it is being done badly, like, surprise surprise, the UK. In that posting there is a picture of people being charged to get across the Thames which makes you think, not road pricing, but: crossing a national frontier, of the sort that is taken seriously.

I ought to have known about this blog two years ago, when it started. But no matter, now I do. This is the kind of thing that you learn if you go to rather boring meetings instead of just staying home glued to a computer, the way I am now. Besides which, a blog is merely a blog. If you actually meet the man who runs it, see his suit and his tie, and hear him talking, quite intelligently, that makes you actually want to pay attention to his blog.

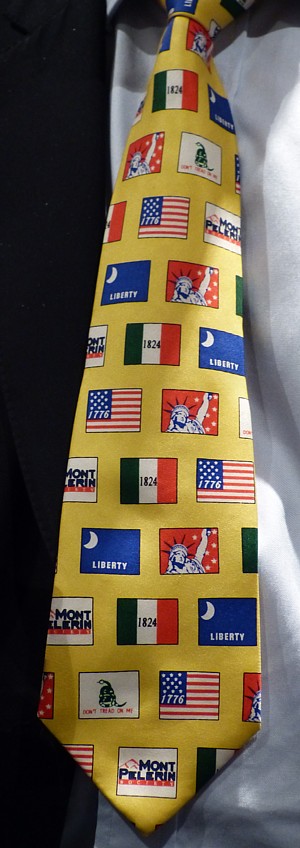

Well, things seem a bit quiet around here today, so here is something I photoed earlier:

I encountered the tie at an IEA event about road pricing. The tie proclaims the fact of and the principles espoused by the Mont Pelerin Society. It was being worn by Dr Eamonn Butler, Director and co-founder of the Adam Smith Institute, and, among many other distinguished things, the author of many fine books explicating and popularising the ideas of freedom and of the free market.

One thing puzzles me, though, and my limited googling abilities were unable to solve the puzzle for me. What was so special about the year 1824? That’s an Italian flag, right? So what happened in Italy that the Mont Pelerin Society regards as so worthy of commendation?

I would have asked Eamonn Butler, but my camera has better eyesight than me, and I only saw the 1824 references when I got home.

A recurring theme in Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature (see some earlier postings here about this book, here and here) concerns how a modern and humane principle, cruelly ignored in the past, then gets over-emphasised. Such a price is worth paying for the triumph of the principle, says Pinker, but the price is indeed a price, not an improvement.

An example being the extreme lengths now gone to in order entirely to eliminate child abductions by strangers (p. 538):

And even if minimizing risk were the only good in life, the innumerate safety advisories would not accomplish it. Many measures, like the milk-carton wanted posters, are examples of what criminologists call crime-control theater: they advertise that something is being done without actually doing anything. When 300 million people change their lives to reduce a risk to 50 people, they will probably do more harm than good, because of the unforeseen consequences of their adjustments on the vastly more than 50 people who are affected by them. To take just two examples, more than twice as many children are hit by cars driven by parents taking their children to school as by other kinds of traffic, so when more parents drive their children to school to prevent them from getting killed by kidnappers, more children get killed. And one form of crime-control theater, electronic highway signs that display the names of missing children to drivers on freeways, may cause slowdowns, distracted drivers, and the inevitable accidents.

The movement over the past two centuries to increase the valuation of children’s lives is one of the great moral advances in history. But the movement over the past two decades to increase the valuation to infinity can lead only to absurdities.

We here nod sagely. This book is full of cherries like that, pickable by people who think along Samizdata lines. But it also includes fruits to please those deviating from correct opinions in quite other directions.

With regard to the matter of children’s rights, libertarians like me are fond of urging property rights solutions for problems not now considered properly soluble by such means, such as preserving endangered species or sorting out such things as the right to transmit radio waves. But it is worth remembering that we applaud the fading of the idea that parents own their children, to the point where they may destroy them with impunity, as if binning unwanted household junk. And yes, such a right to kill faded because it could. The world can now afford to keep all newborns alive. That doesn’t make this any less of an improvement. Well done us. We can understand why so many people were child killers in the past, and still rejoice that times have changed.

The pages where Pinker describes the murderous cruelties inflicted upon many newborns are very vivid. I will never think of the ceremony of christening in quite the same way. He reminds us that what is being said with it is: this one’s a keeper.

A bit of crime-control theater is surely a small price to pay for the pleasure of living in less cruel times.

Last year, for the first time, sales of adult diapers in Japan exceeded those for babies.

– Here. I found it here.

German asparagus in season. Heaven.

– Michael Portillo samples the cuisine of Germany in his latest European Railway Journey.

I am greatly enjoying this show, and am recording it. I am finding it to be a wonderfully relaxing and entertaining way to soak up a mass of historic trivia, such as (this week – just as one for-instance) how Eau de Cologne got started. I also learned about that upside down railway that I have seen so many pictures of but have never pinned down to a particular place.

And not so trivia, because Portillo is focussing particularly on the period just before World War 1. Europe’s last golden age, in other words. Railways were not just for tourists, they were for canon cannon fodder.

This week, Portillo was wearing a rather spectacular pink jacket, of a sort that he would never have risked when being a politician.

Following the Rothbard talk I mentioned yesterday, here is another performance by a dead great guy, in this case Milton Friedman, supplied by Sam Bowman at the ASI blog.

What a shame, as Rothbard so regularly noted, that Friedman didn’t include banking in his list of big businesses that the government should not be giving money and power to.

I say dead. Thanks to their books, but now especially thanks to video and audio, and to the internet that now allows us all to choose what video and audio we will pay attention to, these great men live on.

I never argue. It’s other people who argue with me.

– Roger Hewland, proprietor of Gramex, Lower Marsh, London. Overheard by me, this afternoon.

In a posting at Libertarian Home, Richard Carey quotes the late, great Murray Rothbard criticising Keynes. (And while I’m linking to Carey, see also this recent piece about libertarianism by Carey, which is very fine.)

Better yet, Carey also supplies, as a mere comment added later to the Rothbard posting, a recording of a talk by Rothbard, in which Rothbard also lays into Keynes, way back in April 1989. The talk begins with these words:

First of all I want to launch a pre-emptive strike against any critics who might accuse this talk of being ad hominem. The ad hominem fallacy is that instead of attacking the doctrine of a person you attack the person, and that is fallacious because that doesn’t refute the argument. I’ve never been in favour of that. I’ve always been in favour of refuting the doctrine and then going on to attack the person.

And the talk ends (and yes I did listen also to everything in between) with these words.

To sum up Keynes: arrogant, sadistic, power besotted bully, a deliberate and systemic liar, intellectually irresponsible, an opponent of principle, in favour of short-term hedonism and a nihilistic opponent of bourgeois morality in all of its areas, a hater of thrift and savings, someone who wanted to liquidate and exterminate the creditor class, an imperialist, an anti-semite and a fascist. Outside of that, I guess he was a great guy.

Good knockabout stuff, then, and I greatly enjoyed it, despite the occasional pauses where Rothbard rootles around in his papers for his next bit of dirt. The performance lasts about forty minutes.

But be clear that this is Rothbard in attack dog mode, not Rothbard the magisterial expounder of Austrianism. He surveys Keynes’s career and character, and he does whatever is the opposite of cherry picking. With regard to Keynes’s “will to power” and general belligerence towards anyone he disapproved of, I got more than a whiff of the feeling that it takes one to know one, so to speak. Rothbard had plenty of will to power himself, even if he never got a fraction as much of it as Keynes had from the start. In addition to his great theoretical works, Rothbard spent much of his life flailing about trying to build rather unconvincing political alliances, so that he could get some power, but it never worked.

But give Rothbard time. Keynes wielded huge power in the short run, the short run being, as Rothard explains, the thing that Keynes cared about far more than he did about the long run. But I think it is at least reasonable to hope that in the longer run, say in about a hundred years time, Rothbard may be held in far higher esteem than Keynes. For Keynes also did more than his fair share of flailing, in his failed attempts at serious thinking about economics. If, in the long run, Keynes eventually becomes famous only for being utterly wrong, it would be the perfect posthumous punishment for him.

If, on the other hand, Keynes is still held in high esteem in centuries to come, then heaven help the human species. We are in for very bad times.

Besides which, I think that Rothbard is basically spot on, not only about the character and career of Keynes, but about the need for at least some of us to get nasty about such things. One of the signs that the Cold War was ending was when anti-Marxists started getting serious about what an immoral piece of shit Karl Marx was. Marx did not “mean well”. He yearned for social catastrophe of a sort that he knew would kill millions. He was not just wrong in the intellectual sense, he was wrong morally. He promised his Grand Theory of Everything, failed to produce it, but pretended for the rest of his life that he had produced it. This was not just a great mistake and a great folly. It was morally wrong, because intellectually corrupt. It was a Big Lie.

Similar things can be said of Keynes, and Rothbard says them. Good for him.

Many people are ignorant of many things. This is not surprising and entirely forgivable, given how much knowledge there is to be had, and how much of it is highly specialized. What is less forgivable is how people feel free to spout off and propose things without the slightest idea of the complexities they are dealing with. The French revolutionaries blithely imagined they could create a whole new society with its own rules, just by thinking it up. They ended with a bloodbath in a pigsty.

– Madsen Pirie

The world’s creative activities can be placed along a line. At the good end of this line are the activities that politicians don’t care about, or even better, don’t even know about. The most important quality possessed by such activities is that politicians – by extension, most people – don’t consider them to be important, necessary, vital for the future of our children, etc., so they leave them alone. These things tend to be done well. And at the opposite end of the line, there are the things that politicians and most people do care about, like schools, hospitals, transport, banking, power supplies, broadcasting, and so forth. These things are done anywhere between rather and extremely badly. It is not that they are not now done at all by businessmen. But this is not enough to ensure excellence of output. If the politicians stand ready to be the buyers or lenders of last resort, to “ensure” that this or that is “always” done properly, that it (some scandal or catastrophe that would destroy a proper business) will “never happen again”, then relentless disappointment will ensue. Bad enterprises, instead of just being left to die, are endlessly and expensively fretted over, or worse, coerced into mad purposes that only politicians could dream of caring about, like trying to change (in politics speak: “fight”) the climate. Bad schools or hospitals or banks or power stations or TV channels, rather than just being closed or cannibalised by better ones, are inspected, given new targets and new public purposes, subjected to ever more regulations, asked about repeatedly in places like the House of Commons, and above all, of course, given more and more, and more, money.

It would be tempting for a visitor from the planet Zog to suppose, then, that only trivialities will be done well by twenty first century humans. Luckily, however, both people and politicians have bad taste, and bad predictive powers. As a result, many things are considered to be trivial which are actually not, and they get done and done well. Also, things which are thought to be trivial but which later turn out to be hugely important, but because the politicians and most people at first reckoned them trivial, also get done well, or get done well until such time as the politicians start taking an interest. Alas, things at first considered trivial but later deemed important tend from then on to get done badly, but at least they got done in the first place.

A good example of something which, as of now, is still considered so insignificant as to be beneath the attention of politicians is the computer keyboard.

Computer keyboards have got steadily better and better throughout the last three decades, yet at no point in the story did politicians do any “ensuring” or “supporting” of computer keyboards or of the enterprises that designed and built and sold them, even as more and more politicians became familiar with using such things. No “framework” more complicated than criminal and patent law was imposed upon the enterprise of making computer keyboards. No government minister has particular responsibility for computer keyboards. Computer keyboards thus continue to be made very well, and better with each passing year.

Yet who would now dare to say that computer keyboards are not important? Everyone who ever has anything to do with Samizdata has at least this in common, that they use a keyboard at least some of the time, and in lots of cases, surely for something like half of life when awake. For many a modern working citizen in the year 2012, the big difference – well, a (can you register the italicising of that one letter? – you can now) big difference – between misery and happiness, to update Dickens – the difference between repetitive stress syndrome and constant cursing on the one hand, and daily digital (in the literal bodily sense) bliss on the other hand (talk of metaphorical hands is all wrong in this connection but you surely get my point) – is a nice computer keyboard. → Continue reading: My new computer keyboard

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|