We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Basic logic is something that Mr Richard Murphy, wonderfully flayed by the indefatigable Tim Worstall, is blissfully unaware of. As Tim points out, Murphy reckons we can use inflation to somehow “wash” out massive debt (by shafting savers and others on a fixed income) while he also vents about the terrible plight of pensioners and the need to protect them.

It might be easier to deal with Richard Murphy in the same way that you might an old, very ill dog. Don’t worry, Richard, there would be no pain.

This posting is going to have to be of a more than usually interrogative sort, since I am more than usually ignorant of that whereof I blog, and which I will now copy and paste:

Certainly, on my travels, I’m going to be wary of accepting euro notes with serial numbers that are prefixed with the letters Y (coming from Greece) or M (from Portugal).

I shall also strongly steer clear of notes with the serial numbers starting G (Cyprus), S (Italy), V (Spain), T (Ireland) and F (Malta).

This might sound as if I’m being ridiculously alarmist, but you cannot be too careful.

However, other euro notes should be reasonably safe.

These include those marked Z (Belgium), U (France), l (Finland) and H (Slovenia). As for those with serial numbers beginning with X (Germany), P (the Netherlands) and N (Austria), they can all be used with total confidence.

Is this common knowledge? Am I the last person in Europe to hear about this? I shouldn’t be surprised. You can tell which country printed which Euro. Well, well. Who knew? Who, even now, knows?

The above quoted text is from a Daily Mail piece by Peter Oborne (linked to by Instapundit) about the various economic disasters the world faces. One of which is the melt-down of the Euro.

My big question, aside from wondering who else does or does not know this, is: supposing lots of people do know this, or get to know it, does it not provide a mechanism by means of which mere people might hasten the collapse of the more dubious EUrozone economies, by demanding, when being paid in actual money, to be paid only in Euros printed by the undubious countries?

Perhaps the answer might go: but making such judgments would be, in EUrope, illegal. Maybe so, but that won’t stop a black market making minute comparisons between differently lettered Euros, nor will it stop tourists in other parts of the world, planning their EUropean trips, demanding, once they hear such stories, to receive only the kinds of Euros that they would like. They could, for instance, refuse to accept the wrong kind of Euros, or, if given a mixture of good Euros and bad Euros, sort out the good from the bad and swap the bad ones back for pounds, or dollars, or whatever.

The wrong kinds of Euro notes, from the dubious countries, could soon be treated exactly as if they were forgeries, could they not? The big difference being that these forgeries will be easier to spot.

So, the much prophesied melt-down of the Euro can now be accelerated in a much more discriminating way than merely by people judging that the Euro as a whole will soon be disappearing down the toilet. We will all be able to decide – many may soon be forced to decide – which Euros will descend toilet-wards first. Won’t we? Can’t we? Now? I realise that there is more to money than mere bank notes. But if stories like those sketched above were to start circulating …

Has Oborne got his facts right about this? And if he has, do my supplementary questions also make any sense? As I say, this is all completely new to me, so I could soon, after the first few responses, be wishing that I’d never even asked.

In the United States one of the biggest exercises in false consciousness the world has ever seen – people gathering in their millions to lobby unwittingly for a smaller share of the nation’s wealth

The Guardian’s George Monbiot is talking about the US Tea Party Movement.

Which is it, do you think? Has nobody ever told him about the fixed quantity of wealth fallacy, or does he just enjoy winding people like me up?

“As you march grimly forward through the detritus of economic debate, with a Sturmgewehr 90 assault rifle and fixed bayonet gripped firmly in your hand, thousands of blind Keynesian moles will leap up from deep dark holes in the mud to bite your ankles.”

Andy Duncan. Like Andy, I have read Thomas E. Woods’ Meltdown book and I wrote out some thoughts about it here. And here.

Glad to see Andy is writing away. Old Samizdata hands may remember he used to scribble for us occasionally.

Steve Baker MP’s maiden speech.

Tried to finish a longer piece involving that link, but failed. There’s the link anyway. Now rushing out to a meeting organised by the very organisation that published that blog posting. Such is life.

The ultimate cause of the problem with the banks was indeed chronic government interference, in the form of implicit and explicit guarantees supplied to them free of charge, which hopelessly weakened the entire industry. Reserve ratios – the percentage of deposited cash which is actually retained by the bank rather than lent out – has fallen from over 50% in the 19th century to 2-3% today (or a negative percentage in Northern Rock’s case). That could not have happened in a free market, at least not on an industry-wide scale; nobody would lend to a bank if it tried to take on that much leverage without a government guarantee.

The banking industry had been rendered so unstable by government intervention that it was only a matter of time before it had a crisis, and the crisis could have been brought about by any number of proximate causes. Unfortunately most commentators blame the proximate causes, the particular individuals who happened to be involved at the time, and “free markets”.

In a free market, firms fail from time to time; they aren’t bailed out, people don’t expect them to be bailed out, people arrange their affairs accordingly and so the failure of one firm doesn’t bring down an industry or an economy. Banks were a long way from being a free market.

– “Some Guy” (that’s what he calls himself) commenting on the Bishop Hill piece also linked to below by Johnathan Pearce in connection with Matt Ridley’s inglorious career as a banker

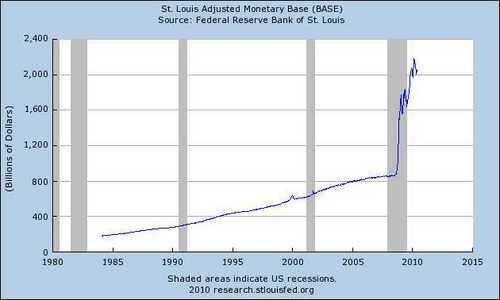

This is a quick thumbnail of money supply for those of you having trouble finding understanding in the tsunami of Keynesian Kool-Aid coming from our ‘betters’.

On October 3rd of 2008, Republicrats and Democans responded to the failure of Lehman Brothers, bankruptcy of Bear Stearns, incipient collapse of AIG Insurance, threatened insolvency of other major financial institutions, and general panic in the financial community, by passing Public Law 110-343. This law contained two basic sections. The most infamous brought us the first of the ‘TARP–ulus‘ genre. But a very important offsetting function was contained in another place in that same law that is known as the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. Way down in the fine print, it authorized the Federal Reserve Bank to begin immediately paying banks to not loan out money. That was not their exact choice of words. In fact, read Section 128 where they did it and it is almost impossible to tell what exactly they were doing.

Three days later on October 6th of 2008, the Federal Reserve Bank announced it would begin paying banks to not lend money. Again, not their exact choice of words.

Within less than a month the Federal Reserve Bank began discreetly ‘monetizing’ by purchasing Fannie and Freddie debt.

By March of 2009, attempts at discretion fell by the wayside and the Federal Reserve began buying US Treasurys outright. Put simply this means that the Federal Reserve began ‘printing’ money and giving it to the United States Treasury to spend.

During this period of time (from September 2008 through current) the St Louis Adjusted Monetary Base went up by approximately 1 trillion dollars.

Since that time, consumer prices have anomalously trended flat (click ‘view data’ for specifics) in spite of the adjusted monetary base more than doubling. How can this be? → Continue reading: Money supply, the stimulus & where is the inflation?

A superb video from the TaxPayers’ Alliance asks…

… how long do you work for the tax man?

Mr Congdon said the dominant voices in US policy-making – Nobel laureates Paul Krugman and Joe Stiglitz, as well as Mr Summers and Fed chair Ben Bernanke – are all Keynesians of different stripes who “despise traditional monetary theory and have a religious aversion to any mention of the quantity of money”

– This is the, er, money quote, so to speak, from an article by the erratic Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, quoting Tim Congdon

“The core problem over the past few decades was not bankers’ greed or the complex financial instruments that enabled them to satisfy it. It was the immense pyramids of debt built up by the Anglo-Saxon half of the world, and the equally massive mountains of savings created in the other. Almost everything that occurred in the past couple of years was, directly or indirectly, a consequence of this.”

– Ed Conway, Daily Telegraph. He has not bought the whole free market line on what is wrong with finance today, but this is pretty good.

As recounted here in a justifiably passionate editorial about the European Union’s plans to beat up the City of London, we are reminded that, whatever the vote might have been in the May general election, that with qualified majority voting in the EU, states can – and do – gang up to put a particular country’s economic affairs in grave difficulty.

Paris and Frankfurt have, in particular, resented the prosperity of the City. And as the recent travails of the euro show, there is precious little to be said for the supposedly wiser governnance of the euro zone. There was a certain amount of gloating after the US and UK got hit by the sub-prime mortgage meltdown (some of that gloating might have been justified) but it is quite clear that the rigidities of the euro zone remain a severe problem.

Why we are in the EU again?

“Yes, we might all think that sending a virtual red rose over Facebook is silly but those sending them (and presumably to some extent those receiving them) do value them. And that value is what we measure when we talk about GDP and it is the creation of that value that allows people to make profits. There is absolutely nothing at all in the capitalist system, the free market one (these are two different things please note), the pursuit of profits or even continued economic growth that requires either the use of more limited physical resources or even the use of any non-renewable resource.”

Tim Worstall, nicely skewering the idea that economic growth is the same as ever rising consumption of finite resources. Not the same thing at all.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|