This is a quick thumbnail of money supply for those of you having trouble finding understanding in the tsunami of Keynesian Kool-Aid coming from our ‘betters’.

On October 3rd of 2008, Republicrats and Democans responded to the failure of Lehman Brothers, bankruptcy of Bear Stearns, incipient collapse of AIG Insurance, threatened insolvency of other major financial institutions, and general panic in the financial community, by passing Public Law 110-343. This law contained two basic sections. The most infamous brought us the first of the ‘TARP–ulus‘ genre. But a very important offsetting function was contained in another place in that same law that is known as the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. Way down in the fine print, it authorized the Federal Reserve Bank to begin immediately paying banks to not loan out money. That was not their exact choice of words. In fact, read Section 128 where they did it and it is almost impossible to tell what exactly they were doing.

Three days later on October 6th of 2008, the Federal Reserve Bank announced it would begin paying banks to not lend money. Again, not their exact choice of words.

Within less than a month the Federal Reserve Bank began discreetly ‘monetizing’ by purchasing Fannie and Freddie debt.

By March of 2009, attempts at discretion fell by the wayside and the Federal Reserve began buying US Treasurys outright. Put simply this means that the Federal Reserve began ‘printing’ money and giving it to the United States Treasury to spend.

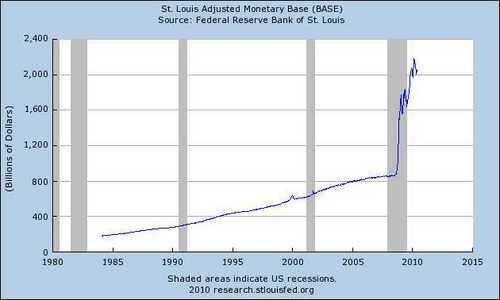

During this period of time (from September 2008 through current) the St Louis Adjusted Monetary Base went up by approximately 1 trillion dollars.

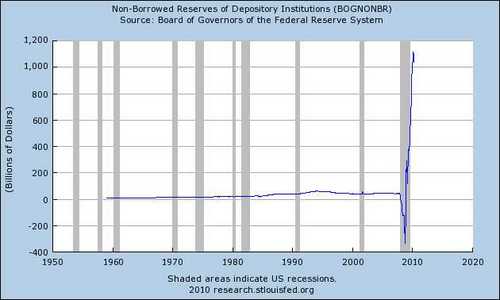

Since that time, consumer prices have anomalously trended flat (click ‘view data’ for specifics) in spite of the adjusted monetary base more than doubling. How can this be? First it is necessary to know what the ‘St Louis Adjusted Monetary Base’ is adjusted for. The ‘adjusted’ part is calculating Federal Reserve issued money and factoring in the fractional reserve multiplier. The adjusted monetary base is the amount of money that would be in circulation if the banks were lending the maximum amount they are allowed to. Banks have consistently lent close to their allowed maximum from at least January of 1959 through August of 2008. But something fundamental changed in September, October and November of 2008. After first faltering far into the red, bank excess reserves went through the roof and punched a hole in the sky.

To be precise, excess bank reserves went up by over a trillion dollars almost overnight. A curious number when recalling that the adjusted monetary base also went up by over a trillion dollars in the same period and consumer prices trended flat. Some detail history.

How was this accomplished? By paying banks interest on unused funds deposited with the Fed. Previously, the Fed had only paid interest on reserves which banks were required (under our fractional reserve banking system) to maintain there; as a matter of policy “excess” reserves received no interest so banks would have an incentive to put those funds to productive use (i.e., to make loans). But as of October 9, 2008, the Fed began paying interest on all reserves, required and “excess” alike. And not just nominal interest, but interest at a rate which is higher than the “Fed Funds Rate” (the rate banks pay to each other for overnight loans), and even higher than current short-term Treasury yields. At a stroke the Fed eliminated for banks interest-rate risk, principal risk, counterparty risk, and even the capital cost of maintaining an extremely high degree of liquidity. The “cost” to banks of non-lending was driven down substantially.

So to put this thumbnail in a nutshell, the Fed has inflated the available money supply by 1 trillion dollars while simultaneously paying banks to not loan 1 trillion dollars. While there is no obvious connection between these two acts, the effect is a simple one. The FRB/Treasury is competing against the free market, effectively borrowing banks’ consumer lending funds to keep the band playing while the lower decks of the nation slip beneath the waves. Killing loans is how they are hiding the evidence and disguising the potential hyperinflationary effect of monetizing. The Fed/Treas has to smother the private loan market or all of that new money they are creating and giving to special interests would show up in the form of doubled consumer prices. Not only is the TARPulus not doing any good, it is doing almost all of the harm. The TARPulus and excess-reserves-interest transactions are taking vast sums of money out of the private sector and distributing it to political factions.

Think of our politically managed economy as a health club with power junkies in charge. Money is power. After cleaning out the checking account and the safe, they are now emptying the cash register. Next step, our lockers will be stripped of valuables (UK pensions, anyone?) and after that, the power junkies will throw us up against the wall and empty our pockets (remember this?)

The problem is not and never was ‘market failure’. It was and continues to be incorrigible government and inevitably corruptible politicians and regulators. This economy could and would have recovered quickly from even the most recent policy created bubble, the real estate ‘boom’, had the advice and opinions of some of us (even here on Samizdata threads) been heeded. The cause of this continually worsening crisis is the repairs the self-anointed experts are inflicting. Paralyzing the lending market, taking money out of the free economy and using it to fund government sector favorites, is like giving muscle relaxants and pain killers for an asthma attack. Sure the stridor of economic desperation diminishes, but that momentary relief is called ‘dying’. And in the end, all the campaign donors’ politicians and all the campaign donors’ cash will only buy them a place on the top deck of the sinking ship.

(My gratitude to Samizdata reader Laird. Without his extensive help researching, phrasing and proof reading, this article simply would not have happened. Thanks, Laird.)

Yeah, I’ve known about this since October 2008. Basically, bank liquidity was a major issue, and it was killing otherwise healthy investment banks(remember, banks very rarely fail, far more often the market loses confidence and they’re crushed by a bank run), so the Fed decided bank balance sheets needed to be propped up. They printed a bunch of money, and then told banks to hold onto it by paying interest. The effect on the real economy is nil(look at what the money supply is, net of reserves), and the effect on the bank balance sheets is markedly positive – now, if a bank is being hit by a run, they have something in the kitty to try to save their asses. When the markets clear up, they destroy the trillion, and stop paying interest on reserves, and it all goes back to normal.

Obviously, it’s not actually that neat. It’s got a few rather pernicious side effects, and nothing works as neatly in practice as it does on paper. That’s doubly true when you’re magicking a trillion dollars into existence. But it was a pretty ingenious attempt, and it hasn’t blown up in anyone’s face yet. Obviously, I can’t call it a success until the whole position gets unwound. But it’s not a failure yet.

Technology, Productivity, Product Quality, Globalisation, also drive inflation down.

Alsadius: “they destroy the trillion”

How? Oh, yes, through tax receipts, no? Or issuing more debt, which is just deferred taxation? So, the Govt prints money and shoves it into the Banks’ OWN accounts so they can keep it there, then, later, it takes our taxes and burns them in the furnace.

All the while we are paying interest somehow – either on T-bills or on the Reserve Accounts.

What can be seen here might be a sort-of “proof” that printing money whilst winding down Fractional Reserve Banking can be finessed as long as money supply is kept stable. The problem, of course, is how to deal with all those pesky loans that the Bank will end up owning outright. Ah, yes, nationalise them. And the defaults.

The quicker we get currency competition and an end to any regulations or restrictions on buying and selling precious metals, the better.

Please allay my confusion… the trillion goes to the banks, who hold it in “profitable” lieu of lending… so where does it end up in the pockets of the unworthy and well-connected? And what action might precipitate its eventual entrance into the everyday money supply, thus triggering inflation?

Myno: The money enters the economy and triggers inflation when the Fed stop paying banks to keep it in their vaults, and they start lending it out… Unless the USG prohibit FRB. 😛

The extra credit was created when the Fed started buying Treasury bonds with the money it printed. Presumably it could be destroyed if the Fed sold the bonds it is holding as a result of those purchases to third party investors and destroyed the payments it received instead of releasing those funds into circulation?

Myno,

The Fed/Treas creates a lot of money out of thin air and spends it gives it to favorites to spend in the economy. Ordinarily this new money would hit the economy and cause massive price increases. So to prevent that from happening, the Fed/Treas borrowed the money from banks by paying them to not lend it to the private sector.

The TARPulus money comes from the private sector loan market, not thin air. If it didn’t consumer prices would be flying high right now.

No, Alsadius. The effect on the economy was not nil. While the effect on circulating money and consumer prices was nil, the private sector lending market shrank. A lot. Yes, real estate loans dropped by 105.7 billion from Oct 1, 08 to April 1, 10, but that money did not move to other needed places in the lending pool. The bad debt chased out good debt and placed the equivalent value in the pockets of the well connected. It did not help lenders it only helped the foolish (to big to fail) debt buyers.

And it didn’t stop there. Business loans dropped by almost 378.2 billion over the same period, revolving credit dropped by 118.9 billion (same period), and yet there was enough spare cash laying around that bank holdings of government securities were able to go UP by 280.1 billion (same period)

Those government securities have to be considered as added excess reserves for purposes of government absorbing private sector investment, IIUC.

This ongoing transaction is nothing less than a transfer of money from the productive part of the economy to the well connected, to big to fail, government favorites.

Er, actually the revolving credit value was through March, not April of ’10.

The flip side of the same coin (as it were).

Here’s the “money quote” from the David Goldman article linked by Alisa:

This symbiosis means that the banking system is in effective government control. As my friend Michael Ledeen–an expert on Italian fascism among many other fields–this is “control without ownership,” or fascism, rather than socialism.

A point which I never tire of making, although no one else seems to care.

Thing is, what *is* ownership, if not the right of use and disposal — i.e. control?

Understood thusly, the distinction between fascism and socialism is merely one of form, not substance.

Exactly, Seerak. In fact, when I got that link in the mail, I mailed back that same money quote, making that same point.

This symbiosis means that the banking system is in effective government control. As my friend Michael Ledeen–an expert on Italian fascism among many other fields–this is “control without ownership,” or fascism, rather than socialism.

A point which I never tire of making, although no one else seems to care.

The problem is we’ve had 70 years of people overusing the word, so everyone has a mental filter that translates “fascism” to “something I don’t like”. My fear has always been when actual fascism returned there would be no way to apply the label to it.

I agree, Eric, which is why I keep insisting on using that word in its technical sense, to apply to the Obama administration.

Thank you Midwesterner and Laird for such a well researched and clearly written article.

Under what circumstances could the Fed stop paying banks to sit on their new excess reserves? Is hyper-inflation and the possibility of currency collapse all that’s left at this point?

Thank you, Mike.

The most likely course I see things following at this point is that the Fed will ‘protect consumers’ from ‘the greedy bankers’ by raising the fractional reserve, possibly as high as 100%. They will cast it as bankers ‘using your money to line their own pockets’ and they will ‘bring order’ to the lending market by requiring all banks to get their lending funds directly from the Fed.

‘In order ensure that’ loans of ‘the people’s money’ are ‘issued in a fair and equitable manner’ the regulators will ‘establish policies to ensure deserving people can get the loans they need’. These policies will be formulated by ‘people with your best interests at heart’ and ‘will assure that loans are not reserved for the privileged’.

They will also ‘work hard’ to ‘rein in speculators’ who ‘profit from the misfortune of others’.

At that point lending will become a politically wielded carrot and stick to exert complete and total control over all of the idiots who drank their Kool-Aid. And the rest of us too. Only businesses that ‘demonstrably contribute to the public good’ will get loans in order to ensure that ‘speculators and profiteers’ will not get loans ‘at the expense of deserving people like yourselves’

Although I agree with most of Midwesterner’s last post, we part ways on the first paragraph. Frankly, I can’t see the Fed raising the fractional reserve rate much above where it now is. This would be a good time to do so, inasmuch as there is so much excess liquidity sloshing around, but our entire banking system runs on fractional reserves and that’s not going to change. (Cue for Paul Marks to jump in on the evils of FRB!) In fact, the US reserve rate is actually among the highest in the world (scroll down in this article for a list), and given the groupthink among central bankers we’re not likely to make that disparity even “worse” (from their perspective).

But I have little doubt that the government is going to become even more heavy-handed in its control of banks, and that lending will become even more politicized.

I wish I shared your ‘optimism’, Laird. Even after the election I would never have imagined a complete national take over of health care so quickly and over so much opposition. I believe it was a goal from the start to give control of bank lending to political apparatchiks. I suspect that as all currencies collapse in synchronicity, central bankers will all together reach the conclusion that they, the central bankers, are the best people to handle this problem. Via some mechanism or another, perhaps Fed administered ‘authorized utilization of reserves’ or some other such charade, that the central banks will take over all control of bank lending.

“Never let a crisis go to waste.”

But I do hope I am wrong.

As I reread my last two comments, I see that I was not clear on how I thought the Fed would go about eliminating fractional reserve banking.

What I expect them to do, either in phased steps or at once, is to in effect if not word, nationalize reserve capacity. No longer will banks lend against their reserves. Instead banks will apply to the Fed for lending funds which will be conditionally issued to them (‘printed’), probably at the aptly named ‘Fed Funds rate’. All money will become central bank money and commercial bank money will disappear.

In one grand act to ‘rescue’ banking, they will take total control of money supply and political control of who gets loans. All in the name of fixing broken capitalism.

Damn, you’re depressing, Mid!

The basic stuff has to be stated – for if it is not people who do not know the stuff can be misled.

So I apologize for saying stuff that most people here already know – but it has to be said anyway (for visitors to the site who do NOT know).

First of all price rises in the shops are NOT a good definition of “inflation” – the traditional definition of “inflation” was a rise in the money supply (whether prices went up or not) and this was a much better defintion. After all some of the most damaging inflations in history (for example that in the late 1920’s in the United States) did not see prices going up in the shops.

If better ways are being found to produce goods and services then prices should actually be going DOWN (not dramatically and not all at once – but in general and over time) if that is not happening then something is wrong (very wrong).

Also “money supply”.

Do we mean “narrow money” (the notes and other stuff the government produces) or “broad money” (bank credit, the inverted pyramid that banks create, by the way an inverted pyramid is not a wildly good structure – all that weight on the capstone, and sometimes the capstone does not even really exist……).

What government have tried to do is to support the vast bubble of credit money (“broad money”) by increasing narrow money (the stuff governments create) and making sure it goes to the banks.

That is why in some countries narrow money (government money) has been exploding in supply – yet “broad money” (bank credit) has not been expanding at all.

However, there are costs to this choice to prevent a massive bust (a collapse of broad money – the sudden “deflation” in the sense of a crash, not a gentle decline of prices over years) and these costs are making themselves felt (in terms of totally distorted capital structure in the economy) and the costs will be felt more and more over time.

Okay so no price inflation because while the Fed has chucked a lot of money at the commercial banks, the Fed is also paying the commercial banks very good interest to encourage them to keep the money in reserves held by the Central Bank. So the money doesn’t filter out into the economy.

But what about the money printing that goes to the govt – i.e.,

“the Federal Reserve began buying US Treasurys outright. Put simply this means that the Federal Reserve began ‘printing’ money and giving it to the United States Treasury to spend.”

Surely this money leaks into the wider economy (e.g., wages, payments to private contractors working with Government). Why hasn’t this generated price inflation?

The Fed is soaking up all kinds of the monitization by pumping up excess bank reserves, TARP, Stimulus and Fed-bought Treasurys.

That’s the ‘beauty’ of this method. It deflates the total pool of currency by reducing lending. The other side, the inflation side, of the equation can come from anywhere. And this system will, superficially at least, work perfectly up until there are no more bank reserves left for sponging up inflation. Then I suspect there will be, as an engineer friend of mine likes to put it, a catastrophic failure mode. That is when they will get serious about asset stripping their opponents and cracking down on hoarders and speculators (aka savers and investors).

After studying this article, and its elucidating comments, I think I finally understand. My confusion arose out of trying to comprehend the cash flows involved in this take-over process. So, if I now understand correctly, there always was a bunch of cash in the private banking market, and the PTB knew that it could only make the Porkulus as large as that amount. What it did was to give a large fraction of that amount of money to special interests, and simultaneously suck it out of the private banking loan market, thus achieving a net zero change in available cash. This kept prices from skyrocketing, but effectively killed the ability of small businesses to get loans. As this was becoming apparent, the PTB stood in front of microphones wringing their hands about the criminal unwillingness of the banks to make such loans… all while having set up a system that guaranteed that result. Cute. Now, in order to get out of this mess, they have ready excuses to go all the way to a 100% fascist banking system. Cute squared. You gotta admire the gall of these punks.

Moreover, not only wasn’t there a stimulating effect from the Stimulus Package, it was set up precisely so that there could not be one. By keeping the currency flat, all they did was to transfer wealth from the small business loan market to the friends in high places market. Only if there were inflation involved, by creating a parallel spending track in addition to the market one, would there be any stimulating effect. So, if no inflation, no stimulus, only diversion.

I don’t know if “it was set up precisely so that there could not be one”, Myno; I think you give these people more credit for evil deviousness than they deserve. They’re just not that smart. But that is indeed how it has worked out.

Your summary of Midwesterner’s article is only partly correct. What you described is simple disintermediation, or “crowding out”. If that were all that was going on, with one borrower (the government) sopping up the available credit to the exclusion of others (businesses), it would be depressing to the overall economy but wouldn’t carry an imbedded inflationary risk. But what we seeing is a combination of disintermediation and monetization of the debt (i.e., “printing money”). The theoretical ability of banks to lend that $1 trillion in excess reserves still exists. Were they to begin lending it, all that excess cash would flood into the market, driving prices up. (This is “price inflation”; Paul Marks’ technical point about true monetary inflation is, of course, correct.)

This is why Mid is so concerned about hyperinflation: its seeds have already been sown. Clearly, that is one possible outcome. Another is a total collapse of the financial system. And, in either case, we could very likely see the “100% fascist banking system” you suggest. Frankly, I don’t see any happy outcomes.

As a workaround, you can start switching to private currency you issue and use with your friends. For instance, you can “be your own banker” with Ripplepay(Link), which lets you track obligations with your associates, and these obligations can themselves be traded as money.

Thanks for a great article Laird and Mike, I passed it on to DR and ZH, this article needs to be expounded upon, there is lots mmore here me thinks!

Thanks for a great article Laird and Mike, I passed it on to DR and ZH, this article needs to be expounded upon, there is lots mmore here me thinks!

Now Jim Rogers says there is (price) inflation. I am not in the US, so who’s right?

That depends upon what you measure, Alisa. Yes, Rogers is right, but for Midwesterner’s purposes he focused on reported CPI. That’s the inherent problem with an article like this; you have to draw the line somewhere, to keep it a manageable length, meaningful and still reasonably comprehensible. You can’t get into everything. Problems with the calculation of the CPI is a subsidiary issue.

The popular press here focuses on CPI, so that’s what everybody thinks of as “inflation”. No one seems to care that the calculation of CPI has been monkeyed with repeatedly; all that matters is what is reported. So naturally politicians do their best to report as little price inflation as possible. There are legions of economists in Washington sticking their fingers into the dike, but inflation is still leaking out; this is just one example. Eventually, though, they will run out of fingers.

The US government is lying about price inflation. Is anybody really surprised by that?

Thanks Laird. You did read the link, right?

Alisa, I decided to deliberately leave many things out of the article to try to keep it somewhat understandable. I agree with (and have long appreciated) Jim Roger’s opinions on things financial. In this case factoring in the problems with the CPI make the case presented in the article stronger, not weaker, so I thought about it and decided to leave them out.

Yes, I read it, Alisa. Good interview. He’s a smart fellow.

OK, so there are two concurrent tactics: one is preventing price inflation from occurring as explained in your article, the other is hiding whatever inflation is occurring despite that tactic by tweaking the CPI. Did I get that right?

Yes. And there are probably more things they’ve thought that we haven’t discovered yet.

Most likely. Thank you both, job well done.

Great post!

So let me get this straight…

The Fed prints the money which the banks borrow at zero. The Fed pays the banks interest on excess reserves. The treasury then comes in and borrows that cash for political purposes.

All the while the Fed keeps the lid on lending in order to prevent inflation. Because of the lack of lending capitalists are starved for cash.

Am I on target?

Not exactly, Babinich. The (commercial) banks don’t play a significant role in the first step. The Fed ‘prints’ money and gives it directly to the US Treasury (without going through commercial banks) and the US Treasury spends as though they had collected it in taxes, using it to meet all the government’s promises. In exchange, the US Treasury gives the Federal Reserve Bank an IOU that promises the tax payers to pay it back. But since the Fed/Treas haven’t actually gotten the money from taxpayers or investors who loan the US Treasury money, the Fed resorts to ‘printing’ it. That means it is increasing the available money supply. Which should cause consumer prices to rise.

There is no hard and fast connection between the ‘printed’ money that the government gets and the bank reserves. It is only a very remarkable coincidence that the two activities offset each other so perfectly. Your last paragraph about the Fed keeping the lid on lending to prevent inflation (caused by ‘printing’ money and giving it to the gov) is spot on.

Babinich – YES you are on target.

Accept the “capitalists” (i.e. businessmen – including the small business people Bill O’Reilly keeps talking about) SHOULD be “starved for cash” if there is not much saving going on (and there is not).

Saying “good business people can not get loans” is no excuse for expanding the money supply.

If people are not engaged in REAL SAVINGS (i.e. not spending some of the money they have actually earned) then good business people should NOT get loans.

Because there are no real savings to lend them – and expanding the credit money supply always ends in tears.

By the way – the above shows that the “good news” presented by the media (that people are buying houses and cars and …… and borrowing to do so) is actually BAD NEWS, because it means the pool of real savings (and of which true investment for the future should come) is not being rebuilt.

If people are spending almost all of their income (or even more of their income) on average – then the economy is doomed in the long run.

The private sector of the real economy is deleveraging by paying back credit from banks. Banks keep what they have in deposits. This would result in a money supply contraction (money deflation) with ensuing heavy price deflation and bankruptcies of a lot of enterprises. Government tries to avoid this outcome by leveraging up. It is increasing its borrowing. These two factors balance each other roughly out. Therefore, we don’t have much price inflation and will not have much in the foreseeable next 12 months.

James Seaberg! Put down the Kool-Aid and step a-way from the bar.

Seriously, your facts such as they are, are correct. You are leaving out the most important facts. First the substantial and unprecedented payment of interest by the Fed on non-borrowed reserves. Look at this table and ignore the non-borrowed (which includes ‘troubled’ institutions) and look at the ‘excess’. The effect was immediate and plateaued in less than three months. A very short time frame for banks to free up that amount of reserves.

Your comment seems to presume that private sector deleveraging is voluntary. It is not. What is not driven by banks’ preference for risk free excess reserves interest payments is driven by other factors. Todd Zywiecki believes that the “tax-and-regulation orgy was spawning unworkable uncertainty for small businesses and banks”

But it is not just market uncertainty working against business lending, it is the regulators themselves. The stimulus to the SBLF (Small Business Lending Fund) is what? A billion dollars? Against a trillion in monitization and excess reserves? And yet at the same time regulators are preventing banks from exercising the judgment and experience that comes from knowing their own customers (yet somehow unable to stop abuse of the government funds) and furthermore, paying banks a very substantial incentive to stop lending and instead, build up excess reserves.

I stand by my assertion from the start, this whole porkulus is not about fixing the economy, it is about pulling money out of the private sector and placing it in government control. The SBLF is just one part of this.

I’ll say it again. This is not the government fixing a market problem. This is the government ‘not wasting’ a crisis that it created. This is a government takeover attempt of the private sector.

Unfortunately, this is based on an incorrect understanding of how the monetary system is currently configured.

The monetary base that you’re referring to only effects Net Transaction Accounts, which are a very small portion of the total bank deposits. There is no federal reserve requirement for all other accounts (savings, etc.), they’re controlled by equity capital requirements.

So what the graph you’ve highlighted is showing, is the banks putting the reserve money that they would have been holding anyway – for day to day operations, and as debt default coverage, and presumably at least some of their more liquid equity capital holdings – on deposit at the Federal Reserve banks so they could get the interest on it.

There’s no impact on the actual money supply. Check the M1 and M2 figures for that – and notice the absence of correlation.

As far as the current and next credit crisis is concerned – it would be better to describe it as a general failure to understand exactly how the banking system evolves as a system. People who were deliberately trying to do the things you’re accusing them of would do a much better job of it than this.

cc

cargocultist,

In this paper(PDF), written in 2003, you will find that

You will also find that

You will also find this discussion of the role of monetary base

Followed by the authors’ caveat that they don’t know if base is useful for forward looking actions intended to influence the market.

Incidentally, this paper is listed under “notes” on this St. Louis Fed chart. That is one scary chart.

To summarize, the trillion plus was created, not transferred. It increases the ‘central bank money’ which has not yet been exposed to the lending multiplier. That is why adjusted base has increased by such a difficult to fathom amount. The only ways I can think of to keep this money from hitting the system are to either ‘buy’ it back out of the economy (ie collect as taxes and then ‘destroy’) or to tamper with the fractional reserve multiplier. The multiplier can be tampered with in two ways, one by ‘borrowing’ the lending capacity of banks by paying interest on it, and the other is to raise the reserve requirement. At some point I expect they will do the latter.

Lest you have any doubt that the Fed is intending to remove commercial bank money from circulation, note that the Fed announces the excess reserves interest as a ratio between the Fed Funds rate and the excess reserves rate. See here, here and here. But when the excess reserves rate actually exceeded the FF rate they stopped doing that.

There has been more than a trillion dollars of adjusted (potential) money created. You may discount what Dirksen said in jest about “a billion here, a billion there” but I hope you can agree that even only a trillion is still “real money”.

Midwesterner,

In every single economics textbook you will find a provably incorrect description of how the banking system works, which only describes the deposit flow around the system – it ignores the effect of loan repayments, and a bunch of other things. It also has no relationship to how the current system works, because of the removal of reserve requirements, and the new dependency on equity capital described by the Basel treaties. But economists believe that that description is correct, and base their theories upon it.

They have rejigged this system so that de facto, the monetary base no longer matters – whether they are aware of that or not, is a very interesting question. All the economists I personally have met, aren’t. As far as the 1 trillion dollar money creation, that was more or less completely offset (again, look at the M1 and M2 figures), by the removal of money from the system by the initial wave of loan defaults and the follow on impact on the equity capital holdings.

You’re quite right in thinking there are major, systemic issues at play here – they’re just not the one that you’re highlighting.

Defaults do not remove money from the system. They add money to the system. When banks lend money in a fractional reserve system, each loan made expands the money supply, each loan repaid shrinks it back. The larger measures of money supply (M1, M2) tend to expand to the fractional reserve limits and yield a stably expanded money supply.

When a loan is not paid back, that money cannot be ‘unspent’. The builders/farmers/whoever still keep the money they were paid with. When the borrower defaults on the loan that those sellers were paid with, that money stays in the money supply. The only way for the defaulted loan money to be removed from the money supply is for other circulating money to be removed in its place.

When the Fed/Treas payed off the defaulted loans (and did other TARPulussy things) they did not do it out of M1/M2 funds. They did it by creating new M0 funds (aka ‘narrow money’, ‘central bank money’). This is pre-fractional reserve multiplier money. That means it can expand M1/M2 by almost 10 fold.

So why is M1/M2 not expanding when M0 is? Principally because of high interest rates payed on excess reserves. As I quoted above:

In other words, (assuming no changes in FR requirements) M1/M2 inflation (which is visible in consumer prices) is impossible without a preliminary expansion in M0. If M0 is expanded, then once the other stresses in the system play out, there will be inflation. The only ways to prevent it are by either shrinking M0, raising reserve requirements, or maintaining incentives to banks to not use the full permitted extent of their lending capacity.

The thing to remember is that M1 and M2 reflect the market’s current response to central bank actions, not the potential range of future responses. The potential range of responses is governed by central bank actions. And in all historical cases I am aware of, once the central bank opened up the doors to inflation by expanding M0, the market, sometimes sooner, sometimes later, responded with hyperinflation.

Being a market phenomenon, the triggering of hyperinflation is generally both delayed and sudden in its onset. But in all cases the base money/M0/narrow money/central bank money/call-it-what-you-will underwent a necessary, enabling expansion first. That first step has now occurred in the US Federal Reserve Note. The odds of that action being reversed or offset are long against.

It rather depends where the defaulted loan is in the system, does it not? The defaults i was referring to were the MBS holdings the banks were caught with in their equity capital holdings when the credit crash hit. That caused money to be removed from the system at a leveraged basis, and was i suspect the main impetus for the tarp bailout and subsequent recapitalisation efforts.

Defaults outside of bank holdings theoretically reduce loan supply, i don’t think it’s entirely correct to equate that with adding to the money supply. However i have never seen any recognition of this effect in any literature, and my suspicion is that this is effectively masked by other the leaks in the system.

These narrow money concepts make no sense imho in the context of the current implementation of the banking system. There are no meaningful reserve requirements, so there is no leverage associated with them. Only net transaction account holdings of greater than $44.4 million are reservable, and banks go to some efforts to ensure that customer money is not held in these accounts if possible. All other savings and deposit accounts are not reservable.

If you regard the money supply as the total amount of money that the banks are allowed to create loans against, then the most significant regulator is the total quantity of equity capital, and there is no effective control of that at present. Nor is there any evidence for the kind of M1/M2 stability that you are claiming over the last 30 years, rather there is simply continuous exponential expansion. If you want to identify the real problems with the system, this is where to look.

I understand and respect that you are quite accurately quoting the textbook on this. Having reverse engineered this system from the FDIC call reports, and Federal Reserve statistical series, it is equally clear to me though that the textbook is wrong.

Also – there is absolutely no way that hyper inflation could ever be a market phenomenon. (Defining hyper as Weimer like.)

Good catch on that last bit. After I posted I wanted to have it back to rephrase it but thought you might catch my point without elaboration. My point is that inflation is loaded into the system through the expansion of M0. The ‘market phenomenon’ I am referring to is the recognition and correction process.

Markets, particularly ones as big as the Fed Note economy, are lumbering leviathans that do not immediately react to inputs outside of their own experience. When they do however, they do so with energy. IIRC, the Weimar situation exactly reflects this in that there was a two year lag between base money monitization and the hyperinflation part of the cycle. What happens is that at some point ‘the market’ realizes that the value of currency has been deeply devalued and it becomes ‘hot’ and is quickly spent (dumped). Velocity goes through the roof.

Banks anticipating a cycle of hyperinflation could be expected to shorten the time spans on their loan portfolios as much as possible by using variable rates where possible and very short terms where not. One might expect deposits to move from supporting 30 year fixed rate mortgages into funding credit card debt. At whatever point in the cycle inflation shows up, bank deposits will dry up as nobody wants to hold money. Debt will be resolved (with inflated currency) to the detriment of the lender and velocity will spiral upwards as the market no longer wants to hold any money at all. Being able to factor the velocity and size of the circulating money supply into transactions becomes paramount to survival.

No doubt as things unravel in this electronic age, the Fed will monitize even more enthusiastically, probably by giving M0 money to connected institutions, to fight leading edge deflation. Throughout the increasing velocity, the political leaders will be pronouncing the economy to be ‘booming’. What they will leave unremarked is the huge redistribution of funds that has taken place in the maelstrom. This article touches very lightly on the delays between monitization and hyperinflation. If I had more time I would look to see what the Weimar consumer bank’s balance sheets were doing during all that.

Mises.org published an article today that fits hand in glove with what I was trying to say when I published this article two months ago.

As far as how I define money supply. Money supply is the amount of fungible money loose in a system. Money used to leverage securities, futures contracts, etc, is not fungible because contracts are valued not at face value, but at market value. At the time they are eventually closed, they do so without effecting the money supply. Incidentally, velocity is a big indicator of a market’s perception of inflation and something to watch closely.

Your idea that the defaults of mortgage backed securities removes money from the system is I think, wrong. But I am beyond being surprised at anything financial so if you want to lay it out step by step, it’s a dead thread and nobody else will mind. My opinion on troubled MBS’s is that they in fact added money to the system via the following route. The Fed/Treas acquired ‘troubled’ MBS’s from the banks with M0 funds and is holding them in their portfolio. The Mises article above covers the rest of the min/max inflation effect these will have on money supply.

If you want to elaborate on what you are saying about reserve requirements (I’m talking exclusively of Fed Notes, not Pounds or Euros) I’m interested. I am quite confident that reserves will approach 100% by whatever means possible as the final explosion approaches. This will be (continue to be) to conceal the underlying inflation of base money being distributed to connected institutions.

It’s not that a lot of what you’re saying isn’t individually true – especially with regard to latency for example, but it, like most of today’s macro-economics is based on core assumptions about the monetary system that are factually incorrect.

A good definition of money for these purposes is i think, the total amount of deposits banks are allowed to engage in fractional reserve lending against.

Let’s start with reserve requirements.

There aren’t any, they’ve been abolished.

That’s not strictly true for the USA although it is elsewhere. The USA maintains reserve requirements for Net Transaction Accounts over a certain size of institution.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/reservereq.htm

and here’s a handy article explaining, if you are a Bank, how to convert your customer’s accounts from Net Transaction Accounts with a reserve requirement to non-net transaction accounts. without one. Apparently you don’t need the customer’s permission to do this in many cases.

http://www.cetoandassociates.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=212&Itemid=102

suffice it to say, they’re a rather small proportion of the total quantity of deposits currently in the US banking system.

Reserves were abolished because they were in fact no longer being used to regulate lending. Lending under Basel compliant systems is a function of equity capital holdings. Examining the call reports for US Banks the relationship appears to be:

equity capital + deposits(liabilities) = loans (assets)

So going back to the role of Base Money in the current system, it really has little or no effect on lending or money creation any more – although it would be very interesting to get a better breakdown on what exactly that $2 trillion the graph is showing does represent for the Banks. My best guess would be the required reserve for Net Trans accounts plus the bank’s own cash holdings (payroll, bonuses, day to day money flows), possibly some equity capital holdings. Or it’s possible they reversed the article i linked to and are in the process of classifying their customer’s accounts back into Net Transaction Accounts so they can get interest on them. It gets a little quantum these days if you think about the reality that money is almost entirely electronic, and spends all its time in the banking system, somewhere.

As for Weimar. Weimar is what happens when you ask for war reparations in cash and don’t specify the exact form of that cash. Somebody in their treasury department had the bright idea to just print as much money as they needed to pay them off, and the rest as they say is history. You can buy Weimar notes on ebay pretty cheaply – it makes for quite a nice display – the time period from 10 mark notes to half million mark notes was about 18 months.

Now that’s hyper-inflation.

I am enjoying this conversation but quite busy (busier) for the next few days. I hope to read these two links and reread and think over your (very interesting) China article and links on Sunday. So hopefully I’ll have some useful observations or questions by somewhere in the Sunday to Tuesday range.

Don’t you sometimes think that looking at monetary and banking systems is a little like watching an elaborate shell game with dozens of shells and an unknown number of balls being played under strobe lights? The only thing we know for sure is the outcome. 🙂

This is a rather slap-dash, hit and run comment as I haven’t been able to dedicate time to it. That is wy it is so long and convoluted. Hopefully you will be able to figure out my points from it.

First, several comments on the C&A article. Based on the statement that “On the contrary, requiring financial institutions to hold a certain percentage of their deposits in reserve, either as cash in their vaults or as non-interest-bearing balances at the Federal Reserve, imposes a cost on the private sector equal to the amount of forgone interest on these reserves—” it appears the article predates the payment of interest on excess reserves. Further, they refer to $11.8 billion in excess reserves as being a high number. The number soared to 1000 times that amount. In general, the article seems to describe an effort for banks to decrease, not increase their money kept in reserves. While I strongly oppose legal tender fractional reserve systems, my article is about how the money generated by the fractional reserve multiplier that was previously at work in the open market, is now being ‘rented’ by the TARPulus crony payoff schemes. At some point that ‘rent’ must either stop (causing hyperinflation) or be replaced with a mandatory increase in fractional reserve ratios.

In short, even if it turns out you are right and there are no reserve requirements, reserves have increased tremendously, none the less. These increased reserves are funds that are no longer in circulation and are being replaced in the circulating currency pool by monitization, by money created and issued to TARPulus recipients.

In your China article I noticed several things of interest. First, it appears from the chart you include that M0, M1 and M2 all increased by approximately the same proportion. I didn’t search out the detail numbers but the chart you give definitely appears to support Friedman’s assertion that inflation is a monetary phenomenon. M0 is under the absolute control of the central bank and I see nothing in that chart to argue against M1 and M2 increases being limited the to the same percentage as M0. For it to be more than that would require a reduction in the functional fractional reserve rate which I don’t think you’ve demonstrated to a significant degree. At least not as concerns the Fed Note. As an aside RE China’s money supply, a four fold increase over ten years considering what has been going on in China’s economy during that time, seems almost conservative when compared to the expansions that have been taking place in nations with shrinking economies.

Another point is the article you reference regarding the ‘Equity Capital exploit’ there appears to be a fundamental confusion in that article. Based on the author’s comment on page four “Assuming that this model were accurate, then the upper limit on commercial bank loans would always be a fraction of the total deposits.” it appears the author may believe that money supply expansion in a fractional reserve of deposits system is less than 1. It is possible to describe numbers greater than 1 as a fraction so I read on looking for further clarification. On the page four/five break she(?) says “This causes the banking system to move from a fractional reserve state, where the total quantity of loans available from the banking system to the economy is less than the total amount of money on deposit in the banking system, to one where total bank originated lending exceeds the total amount of money on deposit.” The first part of that statement is either false or very misleading. For money supply purposes, those MBSs behave as ‘money on deposit’, that is to say, they remove money from circulation. She appears to be counting the redeposit value of the MBSs but not the redeposit value of the borrower’s spending. She appears to be treating loan money as though it is lost from the banking system so let’s look at her explanation.

In her table titled ‘Initial state’, she begins with a loan already in the system but doesn’t show the borrowed money being redeposited in the banking system by whoever the borrower spent it to. If she had, ‘Σ Deposits‘ in the ‘initial state‘ would have been 2000 for a total ‘Σ‘ of 2900. when the depositor withdrew his funds from bank ‘b’ and purchased the 900 MBS, ‘Σ Deposits‘ would have returned to 2000, not dropped to 1100.

Curiously, on the second loan issued she does account for the borrower’s financial activity: “The funds paid as a result of this loan are deposited at Bank B.” She does not seem to understand that loans go right back into banks as deposits. Selling MBSs does not alter the money supply dynamic, its negative effect is one of detaching risk taker (lending institution) from risk assumer (MBS purchaser). I did not read much beyond that point. If I’ve gotten her claims entirely by the wrong end of the stick, please LMK.

The total quantity of loans available in a fractional reserve state is a multiple of te total amount of initial (M0) money on deposit in te banking system. Wikipedia has some very demonstrative graphs here. In fact, the asset multiplier and the deposits multiplier appear to be the same. While this may be significant on some matters (particularly solvency of assets) it does not effect money supply until Fed/Treas TARPulus money is created in M0 to buy it. I did not read all of these links clear through so it is possible that those authors said something farther down that would undo what they said near the beginning. If so, LMK.

To summarize my take on the whole fractional reserve legal tender issue, I strongly oppose legal tender laws in general and where they do exist and cannot be overturned, I oppose the use of fractional reserves of demand deposits.

Fractional reserves generate an almost ten fold expansion in the money supply. This means there are two distinct categories of money; M0 (created by the central bank) and M1, 2, etc (created in the commercial banking system. This creates an extremely high range of potential volatility which has been popularly known at least since Jimmy Stewart explained it (quite well in fact) in It’s a Wonderful Life.

My point in this article is that the Fed/Treas has found a new source of revenue. They have figured out a way to borrow the fractional reserve multiplier. That explosively non-sustainable course of action is the central point I am making here.

Oh, RE Weimar, just substitute ‘war reparations’ with ‘entitlement payments’ and you have the US in the very near future. 8-|