We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

This item, out a few days ago, from one of my favourite bloggers, Tim Sandefur, ought to be part of a firestorm of debate out there over the contempt that the current occupant of the White House has shown for the First Amendment. The sad fact is, however, that a large chunk of allegedly “progressive” or “liberal” opinion (such a shame that fine word has been debauched) is unsteady on defending free speech (and quite a lot of “conservatives” are not much better).

Read the whole thing, as the saying goes. And wonder if you will why not more of a stink has been created about this. Almost a quarter of a century ago, when Salman Rushdie went into hiding in the UK after publication of his Satanic Verses book (I haven’t read it), we had an early taste from how some people were willing to make excuses for the murderous intent of fundamentalist Muslims. But to their credit, lefties such as Christopher Hitchens were willing to take a stand. In fact this was the sort of issue that I think turned Hitch away from some of his reflexive Leftism and into being a more free-ranging contrarian.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, in the course of being interviewed by Sam Harris:

The reason the so-called Muslim “extremists” are so successful at recruiting, keeping, inspiring, and mobilizing people – and then finally getting them to wage jihad – is that what they’re saying is fully consistent with the teachings of Muhammad.

My thanks to the ever alert Mick Hartley to alerting me to this interview. Hartley entitles his posting “The faith has no truly moderate wing”. That is certainly how Islam seems to me when I read its scriptures.

It may of course just be wishful thinking on my part, but I predict that, some time within the next hundred years or so, there will be a mass-abandonment of this horrible religion, by all those who find themselves being raised as Muslims but who just want to be human beings, rather than in a state of perpetual war – at best mere ceasefire – with all non-Muslims, and constantly at the mercy of lunatic preachers nagging them to actually do what they still go through the motions of saying they believe. The only truly effective way of shaking free from such influences is to say that the lunatic preachers are wrong about everything – about Allah, about the obligation to submit to Allah, about the whole damn thing. It is because they fear what I hope for that devout Muslims have always threatened such mayhem if anyone now proclaims themselves in public to have abandoned Islam, like Ayaan Hirsi Ali. The effort to establish the right to abandon Islam unmolested is a key locus in the righteous struggle to reduce Islam to insignificance and political impotence.

Christians often complain that atheists only complain about Christianity, rather than about Islam. This criticism does not apply to Sam Harris.

Speaking in this video, Steve Baker makes a point that cannot be made too often:

It’s a crazy thing. In most price systems or most parts of the economy, people understand that it’s wrong to plan prices. So here we are, we’ve had chaos in the credit markets, and the credit markets are centrally planned by a cooperating international network of central banks, committees of planners, who deliberately alter the height of interest rates. And we don’t make the connection that central planning causes chaos. And it’s just a really simple thing, and it’s true in money and banking and it’s true in everything else.

Making our case on financial matters can get difficult, because it can quickly get bogged down in arcane detail. Talking about the interest rate as a politically imposed price works well, because the idea is so clear and so straightforward.

Baker has just been voted onto the Treasury Select Committee. I know very little of the inner workings of Britain’s Parliament, but those who know better about such things I tell me that this is a very big deal. The Guido Fawkes blog certainly thought this circumstance worth a passing mention. This man is making headway.

When I first heard the newly elected Baker talking about what he hoped to accomplish, he sometimes sounded like he thought that the Keynesian/Quantitative Easing door was so rotten that it might only need a few good kicks to be destroyed. Well, hope springs eternal and this door was and is very rotten indeed, but it is also very powerfully defended. Baker now talks like a man who is definitely in for the long fight. Good.

It is the First of May, a date traditionally associated with Marxism. Let us therefore pause today to remember that at least 100 million people were killed by Marxist governments in the 20th century, a number that dwarfs the predations of every other organized movement in human history.

Richard Carey is a devoted student of the English Seventeenth Century and of its ideological struggles in and around the time of the Civil War. Tonight, he will be giving a talk about all this at the Rose and Crown in Southwark, and I will definitely be there.

There could hardly be a more important subject for an English libertarian. Libertarianism now has a rather American flavour. The biggest libertarian books, especially those of more recent vintage, tend to be written by Americans or at least in America. So, if it is the case (and it is) that libertarianism of the modern and self-consciously ideological sort actually has its origins in the English Seventeenth Century, then that is a fact that we English libertarians should regularly be celebrating and reflecting upon.

My own off-the-top-of-my-head take on this is that libertarianism of the sort I espouse most definitely did make its first big appearance in Seventeenth Century England, in the form of the Levellers. But the impeccably libertarian nature of this first great libertarian ideological eruption has been masked by the kinds of questions that most exercised those first English libertarians. Libertarianism now tends to be about what governments ought to do, and most especially about the many things that governments now do, but ought not to do, or at the very least to do much less. In the seventeenth century, libertarians with unswervingly libertarian views on, e.g., property rights as the correct institutional foundation of liberty, were not quite so exercised about how the government should behave, although they did have plenty to say about this. Their central concern was: Who has the right to be the government in the first place? If you do have to have some kind of government, who should choose it? The central preoccupation of those Levellers was: Where does political authority come from? If there must be government, who decides about who shall be that government?

Charles I – famously or infamously according to taste – claimed that God had chosen the government of England, in the form of … Charles I. This the Levellers, of course, challenged. But having challenged it, and the king having been executed, the question remained: If Charles I is not the legitimate ruler of England, then who is?

The Levellers were “egalitarian” in the sense that they were indeed far more egalitarian about who should be allowed to participate in that political debate, about who should govern. Political authority sprang from … everyone! When it came to deciding who the government was, everyone’s voice counted. This was the sense in which the Levellers really were, sort of, “levellers”.

But this political egalitarianism was seized upon by Seventeenth Century Royalists as evidence that the Levellers were also egalitarians in the modern sense, who believed that economic outcomes should be equalised by the government. They were accused of being socialists. There were indeed real socialists around at that time. These were the Diggers. But the Levellers had very different views to the Diggers.

Later, the Levellers were proclaimed to be socialists by another ideological tendency, namely … socialists.

The irony being that these later socialists mostly had ideas about how government should conduct itself were pretty much identical to those of Charles I. Charles I believed that the state (i.e. Charles I) had relentlessly to intervene in the market and in the workings of the wider society, in order to correct freedom’s economic and other injustices, and never mind any harmful consequences that flowed from such intervention, or “tyranny” as the Levellers called such activities. Modern socialists believe exactly the same, about themselves.

So, the Levellers, historically, have been caught in a pincer movement of lies, proclaimed by two different brands of statists. Royalist statists accused the Levellers of being socialists. Subsequent socialists claimed the Levellers as socialists. Both were wrong. But if we libertarians do not now correct these errors, nobody will.

I still recall with great pleasure the talk that Richard gave at my home last year about the ideological context within which the Levellers first arose, and the questions that they were most keen to answer. Tonight, I am hoping to learn more about the answers they gave to these questions, and, in general, about the nature of their libertarianism. Because libertarianism is most definitely what it was.

I wrote this posting in some haste, to be sure that what I wrote got posted in time to encourage at least some who otherwise might not have done to attend Richard Carey’s talk this evening. I am fully aware that the above is a highly schematic and simplified version of a very complicated story. I have, in particular, supplied no linkage to pertinent historical writings. Comments and corrections, especially with links to pertinent material, will be very welcome to me, and I’m sure to others also.

LATER: I see that in his piece about Richard (linked to above), Simon Gibbs includes yet again an earlier picture taken by me, of Richard sporting lots of hair like a down market Cavalier. Now he looks more like this:

Technically, that is not a good photo, but it’s the best I can do right now.

Hair matters a lot, when it comes to Seventeenth Century English ideological disputes.

The other day I wrote a post about the plight of the Bushmen living in the Kalahari desert in Bostwana.

Jaded Voluntaryist commented,

Survival International are a bunch of arseholes who would see brown skinned human beings being prevented from rising out of the mud because it’s just so quaint. I wouldn’t take their word for it. Of course that may not be what’s happening here, but they don’t have a great track record.

They moaned for example when the Saint family (at the cost of several lives) brought Christianity to the Huorani tribe in Ecuador, which helped reduce their murder rate down from somewhere in the 70% region. Hardly anyone lived to old age. No one would deny that not everything the Huorani got from contact with the developed world was good, but only a sociopath would want them to keep living as they were.

I replied,

I take your point about the patronising attitude of groups like Survival International, although I have also heard that they sometimes do good work on the ground protecting tribal people from state and other violence. As I am sure you agree, if any particular Bushman wants to carry on as his or her ancestors did, good luck to them, and if he or she wants to head to the relatively bright lights of Gabarone and seek their future there, good luck again.

However it looks very strongly as if the Botswanan government has taken away the option for Bushmen to live in their traditional way by the use of a mixture of force (eviction from their ancestral hunting grounds and the hunting ban) and state “help” (the infantilising effects of welfare as pointed out by Mr Kakelebone).

I may write a post someday about the superiority of the attitude of Christian missionaries towards tribal people compared to the attitude of groups like Survival International towards tribal people. My argument would not be based on the fact that I am a Christian, nor on any general assessment of how much or little I admire the hunter-gatherer lifestyle (which might vary widely between different groups). My argument would be that the missionaries wish to persuade some other human beings to believe as they themselves believe, whereas the “protectors” wish to keep them as living museum exhibits. They always remind me of those science fiction stories in which Earth is kept ignorant / keeps other planets ignorant of faster than light travel and so on. My sympathies are nearly always with those who say, “Screw the Prime Directive”.

Then I said,

Come to think of it, screw the “I might write a post someday”. I will cut and paste the above comment as a post right this minute.

Ten years ago I thought their days might be drawing to a close: Kalahari Bushmen, New Age Travellers and the paradoxes of state welfare

…perhaps their ancient way of life was doomed anyway by contact with modernity, but any slight chance it may have had to either adapt organically or fade away by consent was finished, and its end made more bitter, by government efforts to help.

And so it has proved: Botswana bushmen: ‘If you deny us the right to hunt, you are killing us’

For Jamunda Kakelebone, a 39-year-old bushman, or San, whose family has always lived as hunter gatherers, what is happening in the Kalahari desert is deeply disturbing. Not only have bushmen families like his been moved from their ancestral land to make way for tourists, diamond mining and fracking, he says, but those who remain are now no longer allowed to hunt.

The final blow came in January, when a ban came into effect prohibiting all hunting in the southern African country except on game farms or ranches. The new law – announced by the minister of wildlife, environment and tourism, Tshekedi Khama (brother of the president, Ian Khama) – effectively ends thousands of years of San culture.

…

In a series of evictions after 2002, the Botswana government removed several thousand San from the Kalahari reserve, claiming they were a drain on Botswana’s financial resources and that the families were happy to give up their hunter-gathering. But, say human rights groups like Survival International, the evictions were intended to allow in conservation groups, tourist companies and diamond mining.

Around 350-400 San people now live in seven “settlements” in and outside the game reserve, many of which are in appalling conditions. “Instead of being allowed to hunt, we are taken to resettlement camps and must depend on government for handouts. It’s like holding your arms and expecting to be fed. They treat us as stupid. We are given clothes and food.

The speaker, Jamunda Kakelebone, is pictured with his lawyer outside Clarence House in London. Someone should have warned Mr Kakelebone that some aspects of his message might be ill-received in a land where strong taboos hold sway.

Why be libertarian? It may sound glib, but a reasonable response is, Why not? Just as the burden of proof is on the one who accuses another of a crime, not on the one accused, the burden of proof is on the one who would deny liberty to another person, not the one who would exercise liberty. Someone who wishes to sing a song or bake a cake should not have to begin by begging permission from all the others in the world to be allowed to sing or bake. Nor should she or he have to rebut all possible reasons against singing or baking. If she is to be forbidden from singing or baking, the one who seeks to forbid should offer a good reason why she should not be allowed to do so. The burden of proof is on the forbidder. And it may be a burden that could be met, if, for example, the singing were to be so loud it would make it impossible for others to sleep or the baking would generate so many sparks it would burn down the homes of the neighbors. Those would be good reasons for forbidding the singing or the baking. The presumption, however, is for liberty, and not for the exercise of power to restrict liberty.

A libertarian is someone who believes in the presumption of liberty. And with that simple presumption, when realized in practice, comes a world in which different people can realize their own forms of happiness in their own ways, in which people can trade freely to mutual advantage, and disagreements are resolved with words, and not with clubs. It would not be a perfect world, but would be a world worth fighting for.

– The concluding paragraphs of Why Be Libertarian? by Tom G. Palmer, which is the opening essay in Why Liberty? edited by Palmer for the Atlas Foundation.

Here’s a picture of Palmer waving a copy of Why Liberty? during the speech he gave to LLFF14 at University College London last weekend:

Free copies of Why Liberty? were available to all who attended.

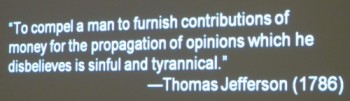

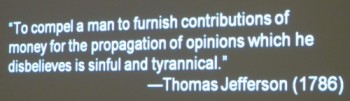

Here is part of slide number one of Christopher Snowdon’s talk at LLFF14 yesterday afternoon, entitled “How the state finances the opponents of freedom in civil society”:

That is from The Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom, first penned, it would seem, in 1779, and actually passed in 1786.

Christopher Snowdon is described here as the “Director of Lifestyle Economics at the IEA”, which means he is their chief complainer about sin taxes.

His talk yesterday was based on the work he did writing two IEA publications, Sock Puppets: How the government lobbies itself and why and Euro Puppets: The European Commission’s remaking of civil society. Both those publications can be downloaded in .pdf form, free of charge.

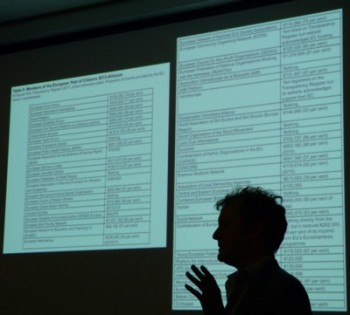

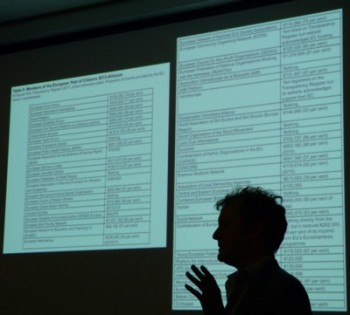

Snowdon walked around a lot when talking, so although I took a lot of photos of him, only this one was any good:

Behind Snowdon is a long list of NGO’s which receive substantial funding from the EU. For legible versions, see Euro Puppets.

In the short run, all this money paying for leftist apparatchiks to lobby for more money for more leftist apparatchiks is good for leftism, but I wonder if in the longer run it won’t be a disaster for them. Another quote, about how all causes eventually degenerate into rackets, springs to mind. This is the kind of behaviour that even disgusts many natural supporters of leftism. As Snowden recounted, few people outside this incestuous world have any idea of the scale of this kind of government funding for “charities”, never mind knowing the extra bit about how the money is mostly used to yell and lobby for more money, and for more government spending and government control of whatever it is. In particular, Snowden recounted that when John Humphrys interviewed Snowden on the Today Programme, he (Humphrys) did not grill him (Snowden), he (Humphrys) mostly just expressed utter amazement at the sheer scale of government funding for “charities”, for anything.

What this means is that if and when a non-leftist politician gets around to just defunding the lot of them, just like that, he gets a win-win. He cuts public spending, even if only a bit. And he slings a bunch of parasites out into the street where they belong, who are then simply unable to argue to the public that they were doing anything of the slightest value to that public. Insofar as they do argue that they shouldn’t have been sacked, they do not further their own cause; they merely discredit it further and further prove that the decision to sack them was the right one.

One of the most encouraging things happening to the British pro-free-market and libertarian movement is the outreach work being done by the Institute of Economic Affairs, to students at British universities and in British schools. In this IEATV video Steven Davies and Christiana Hambro describe what they have been getting up to in this area. They are a bit stilted in their delivery and demeanour. Steve Davies in particular is a rather more relaxed, animated and persuasive public performer than this short video makes him seem. I get the feeling that there were retakes, as they negotiated car doors and seatbelts when on camera. But if any of this inclines you to be put off, don’t be, because the process these two excellent people are talking about in this video is definitely the genuine article.

They mention the Freedom Forum. This has, says Davies “rapidly become the biggest gathering of pro-liberty students and young people in the UK”. The latest iteration of this, Liberty League Freedom Forum 2014, is happening next weekend and its detailed timetable has just been announced. If this get-together was just a one-off annual event with nothing else related to it happening, that would definitely still be something, although I do agree with those who say that the title of these things is a bit of a mouthful. But LLFF2014 is a great deal more than just an annual event, being but the London manifestation of a much bigger program of intellectual and ideological outreach to universities and to schools throughout the UK.

Recently I dropped in at the IEA, where Christiana Hambro and her IEA colleague Grant Tucker made time to tell me in person about what they have been doing. I also picked their about people who might be good to invite to talk at my last-Friday-of-the-month meetings. For me, the most interesting thing that they said to me was in answer to my question concerning to what extent their outreach activities were piggy-backing on the earlier efforts of the Adam Smith Institute, efforts which have been going on for many years, under the leadership of ASI President Madsen Pirie. What Christiana Hambro and Grant Tucker said was that when it came to outreach to universities, then yes, their work does depend on earlier ASI efforts. University economics departments are tough nuts to crack open with contrary ideas, and the best way to get to universities is by working with free market and libertarian student societies, rather than relying on the intellectual hospitality of academics. The ASI has done a huge amount to encourage such groups over the years, and without such groups what the IEA is now doing in universities would have been harder to accomplish.

But in schools, it has been a very different story. The ASI has done plenty of work in schools as well over the years, but what Christiana Hambro and Grant Tucker said to me was that basically, in schools, the IEA’s outreach operation is basically operating in virgin territory, with economics pupils all of whom have heard of Keynes, for instance, but none of whom have ever heard of Hayek. Another way of putting that might be to say that when it comes to preaching free market economics to British schools, this is a town that is plenty big enough for the both of them.

Schools are also different from universities in often being much more open to different ideas than universities are. Universities are dominated by people who take ideas seriously, but this can have the paradoxical result that many universities and university departments become bastions of bias and groupthink, all about deciding what is true and then defending it against all heretical comers. Schools, on the other hand, some at least, are more concerned to persuade their often indifferent pupils to care, at all, about ideas of any kind, which, again rather paradoxically, makes many such schools far more open to unfamiliar ideas than many universities. A teacher may be a devout Keynesian, even a Marxist. But if these IEA people from London can help him stir up his pupils’ minds by showing economics to be an arena of urgent and contemporary intellectual and ideological conflict rather than merely a huge stack of dull facts mostly about the past, then he is liable to be very grateful to these intruders, even if he flatly disagrees with their particular way of thinking.

Present at this Liberty League Freedom Forum that is coming up next weekend, which I will be attending (just as I attended LLFF2013 last year), will be some of the products of all this outreach. Someone like me has heard most of the featured speakers before, some of them many times. But many of the people at LLFF2014 will be hearing talks from people only a very few of whom they have ever encountered before. Here are some of the topics which they may find themselves learning about: Public Speaking and Networking, Doing Virtuous Business, How To Be A Journalist, and (my personal favourite) Setting Up A Society (i.e. a school or university pro-liberty society).

As for me, no matter how many times I hear Steve Davies speak, I am always keen to hear what he has to say about something new, and this year, I am particularly looking forward to him answering the question: “But who will build the roads?” In my opinion, when Libertaria finally gets going, somewhere on this planet, defence policy (often regarded as a big headache) will be very simple. Just allow the citizens of Libertaria to arm themselves. But, building “infrastructure”, while nevertheless taking property rights seriously (instead of merely taking seriously the idea of taking people’s property from them to make infrastructure) will, I think, be much more tricky. I look forward very much to hearing what Davies has to say about this.

Too bad that his talk clashes with the one about Setting Up A Society. I’d love to sit in at the back of that one also, and maybe I will pick that one on the day. That such clashes will happen is my one regret about this event. But you can see why they want to do things this way. As well as big gatherings, they also want small ones, in which new talent feels more comfortable about expressing itself, and flagging itself up as worth networking with, by other talent.

I recall writing a blog posting here a while back, in which I described a talk I heard the IEA’s then newly appointed Director Mark Littlewood about his plans for the IEA. Right near the end of that piece, which I think still stands up very well, I wrote that: “there is now considerable reason to be optimistic about the future of the Institute of Economic Affairs”.

There still is, and even more so.

We’ve all felt that need to tell the hard truth. Assert the raw and unadorned core repeatedly and dogmatically. React with righteous anger and fury, even without elaboration, to the point of being downright offensive. There is a role for this. Injustice in our midst — and there is so much of it — cries out for it. I wouldn’t call this brutalist. I would call this righteous passion, and it is what we should feel when we look at ugly and immoral things like war, the prison state, mass surveillance, routine violations of people’s rights. The question is whether this style of argument defines us or whether we can go beyond it, not only to lash out in reaction — to dwell only in raw oppositional emotion — but also to see a broad and positive alternative.

– Jeffrey Tucker, whose recent essay on what he sees as being the less charming features of libertarian commentary has provoked quite a storm, thereby validating his point.

“Charges dropped against Spurs fans’ Yid chants”, reports the Tottenham and Wood Green Journal.

About bloody time. The charges were more than usually malicious and absurd. The usual level of malice and absurdity is to pretend that certain syllables – called “racial insults” among the illuminati – are magic spells infused with the irresistible power to turn any mortal that hears them into a raging savage. It was the rare achievement of these charges to be crazier, nastier and more insulting to the intelligence and decency of ordinary people even than that.

As reported by the Jewish Chronicle, although by shamefully few of the other reports of the case, the men charged had said “Yid” not as an insult but as a way to cheer on their own team. All three men are Tottenham Hotspur supporters. They may be Jews themselves; I could not find a source that stated whether any of them are or not, but given that they are Spurs fans it could well be the case. I found an interesting article in Der Spiegel (no need to say the obvious) that gave a brief but clear explanation of this phenomenon:

Tottenham Hotspur’s Jewish background is similar to the Ajax [a Dutch football team] story. The north London club was popular among Jewish immigrants who settled in the East End in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “The Spurs were more glamorous back then than the closer West Ham United or Arsenal,” says Anthony Clavane, a Jewish journalist with the tabloid Daily Mirror who published a book in August about how Jews have influenced the history of English football. Additionally, other northern London districts, such as Barnet, Hackney and Harrow, have traditionally been home to many Jews, which has also contributed to the Hotspur image.

So, for historical reasons the Tottenham Hotspur home stands sing of their own as the Yids, the Yiddos, or the Yid Army. For this it was proposed to put three men in jail. From the Jewish Chronicle link above,

Their arrests followed widespread debate late last year, after the Football Association issued guidelines in September announcing that fans chanting the word “Yid” could be liable to criminal prosecution.

The move caused anger among Spurs fans, who refer to themselves as the “Yid army” as well as the Tottenham Hotspur Supporters Trust, which stressed that “when used in a footballing context by Tottenham supporters, there is no intent or desire to offend any member of the Jewish community” .

Following the example set by everyone from the Desert Rats to Niggaz Wit Attitude they have taken what was once an insult and turned it into a badge of honour. Tasteless? Possibly. Knowing nothing of the history of a Jewish link to Tottenham Hotspur FC, I recall once being shocked to see a blackboard outside a pub advertising a forthcoming match to be televised there as a contest between the “Yids” and whatever team were to oppose them. I mumbled an attempt at protest to a barmaid who had stepped outside for a fag. She didn’t know what I was talking about – in retrospect I’m not sure she even understood that “Yids” had any other meaning than a nickname for THFC – and I slunk off in embarrassment. One could certainly argue that it it is a poor memorial to the persecution and mass murder suffered by Jews over the centuries to make an insult used against them into a means to excite collective euphoria among people watching a game. But if you really want to contemplate great barbarities memorialised in plastic, turn your eyes to the attempts of the Crown Prosecution Service to charge Gary Whybrow, Sam Parsons, and Peter Ditchman with racial abuse, and smear them as anti-semites, for asserting the Jewish identity of their own team.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|