We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Incoming from my friend Tim Evans:

Today is the sixty-first anniversary of one of the most extraordinary actions by a British army unit during the Cold War. Please, just spare 9 minutes of your time to quietly watch and reflect on a battle that has long fascinated me: the Battle of the Imjin River.

I’ve been out and about most of the day, but tomorrow morning, I will do what Tim suggests.

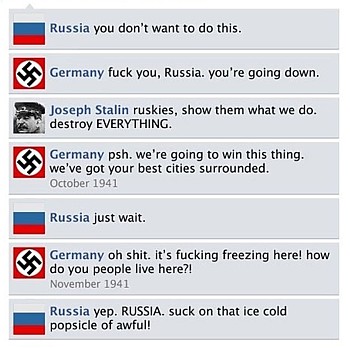

Oh, the joys of counterfactual history:

“Woodrow Wilson, by contrast, inserted the United States into World War I. That was a war that the United States could easily have avoided. Moreover, had the U.S. government avoided World War I, the treaty that ended the war would not likely have been so lopsided. The Versailles Treaty’s punitive terms on Germany, as Keynes predicted in 1919, helped set the stage for World War II. So it is reasonable to think that had the United States not entered World War I, there might not have been a World War II. Yet, despite his major blunder and more likely, because of his major blunder, which caused over 100,000 Americans to die in World War I, Wilson is often thought of as a great president.”

“The danger is that modern presidents understand these incentives. Those who want peace should take historians’ ratings of presidents seriously. Beyond that, we should stop celebrating, and try to persuade historians to stop celebrating, presidents who made unnecessary wars. One way to do so is to remember the unseen: the war that didn’t happen, the war that was avoided, and the peace and prosperity that resulted. If we applied this standard, then presidents Martin van Buren, John Tyler, Warren G. Harding, and Calvin Coolidge, to name four, would get a substantially higher rating than they are usually given.”

Thanks to EconLog for the link.

Of course – and this is going to get debate going – if the US had not entered WW1, how do we really know what would or would not have happened several years hence? What configuration of forces and political developments would have arisen? There is simply no way anyone can know for sure.

Seeing as this year marks the bicentenary of the War of 1812 and seeing as I know precious little about it, I thought I’d ask the commentariat the following:

1. Who were the good guys and who were the bad guys?

2. Who won?

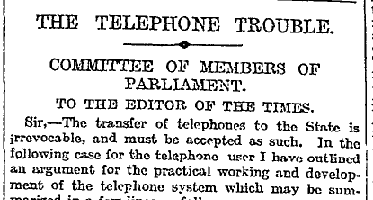

I am glad you’ve asked. Not well, it would appear. Over in 1912 they’ve had less than two months of it and even the politicians are beginning to notice:

A majority of complaints fall under the following headings:-

1. Premature disconnexion.

2. Interruptions to conversations by operators.

3. Wrong numbers given.

4. Delay in answering calls…

Etcetera, etcetera…

Do they know why? Yes they do:

…the incentives inherent in a private concern to give the best no longer prevail. It will suffice to state that in Government concerns initiative is often dormant, staffs are largely permanent, and not necessarily promoted by merit or dismissed on inefficiency, and the system of organization generally stereotyped and non-progressive.

So, are they going to do anything about it? Not exactly:

The transfer of telephones to the State is irrevocable, and must be accepted as such.

Fortunately, “irrevocable” turned out to mean “until 1984” when British Telecom was privatised.

The Times, 22 February 1912. Click to enlarge.

Update Title changed so that it makes sense.

Your teeth belong to the collective.

– From a Planet Money piece quoted by Alex Tabarrok (who was linked to today by David Thompson), about how China went from the bad old days of the Great Leap Forward to the better days that followed. The above words, which Thompson also singled out for attention in his link, were an answer to a property rights query to those in authority, in the bad old days. Do we even own our teeth? No you do not.

The switch from collective “property” to actual property, as Tabarrok makes clear, was initiated by the people of China, rather than by their rulers. It began in the village of Xiaogang, whose farmers decided to go back to actual property for each individual farmer and his family, with immediate beneficial effects. And then it became a movement. The rulers of China didn’t decide to make this change. They merely decided not to stamp it out.

Madsen Pirie’s new book, Think Tank: The Story of the Adam Smith Institute was launched earlier this evening in the crypt of St John’s, Smith Square. Here is what it says in the book’s first chapter, entitled “Shaping an institute” (pp. 3-4):

There was an institute in London which drew heavily on Smith’s ideas, and those of the free-market economists who had followed in his wake. This was the Institute of Economic Affairs (lEA), founded by Sir Antony Fisher twenty years earlier, and which had published a steady stream of monographs analyzing the deficiencies of central direction, state planning and economic intervention. They were intellectually rigorous, and had made their way into the literature of economics libraries, albeit in a separate corner, almost fenced off from the mainstream.

But we wanted something more. It was all very well to win theoretical arguments, but nothing seemed to happen afterwards. Governments continued on their unruly ways, while academics devised new follies to set up on the wreckage of the old ones. We wanted to change reality; to have an impact on what actually happened. We wanted to make policy.

Adam Smith might have been one strong influence on our thinking, but there were others. One was James Buchanan, the Nobel Laureate who, with Gordon Tullock, James Niskanen and others, developed what came to be known as Public Choice Theory. In essence ‘it took the ideas of economics into the domain of politics and administration. Instead of ‘treating politicians and civil servants as selfless seekers after public good, the theory treated them as if they were ordinary economic participants, out to maximize their own advantage, just like other people. it proved a very fertile theory tor explaining what would otherwise have been incomprehensible outcomes. It also fitted in with the rather less than respectful way that we ourselves regarded politicians.

Public Choice told us how minority interest groups could hijack the political agenda to have advantages created for themselves. It explained how politicians respond to pressure from vociferous and self-interested groups, but not from a public at large which might be largely unconscious of the effect policy made upon it. Public Choice Theory was basically a critique, but we began to wonder if there could be a creative counterpart to it. Just as Public Choice Theory told us why certain policies were doomed to political failure, however economically sound they might be, could it not be used to create policies that would not be subject to these limitations? Could new free-market strategies be crafted that flowed with political reality by building in the support of the interest groups which might otherwise derail them?

This was powerful stuff. …

Indeed it was. As soon as I’ve read the rest of this book, I’ll tell you what I think of it.

Meanwhile, here is a picture I took at the launch, of the author hard at work signing copies.

Not surprisingly, the ASI blog already has a posting up on the subject.

One of my hobbies is to browse the pages of the (London) Times from a hundred years ago. As I intend (though I promise nothing) to write the odd post around articles from the time I thought it might be a good idea to describe (as best I can) the world in 1912. Or, at least, the world as seen through the pages of the Times which is a potentially dangerous thing to do. Imagine, for instance, describing the world of 2012 with the BBC News as your only source.

I cannot read articles from 1912 without being aware that there’s a big war coming up. A huge war. A Great War. A war that will change just about everything. Mostly for the worse. But can I see it coming? Not really. There clearly are tensions between Britain and Germany. Last year two British officers (Brandon and Trench) were jailed for spying. Seeing as one of them went on to become a leading light in MI6 it looks like the Germans got their man. More to the point it demonstrates that there is a lot of distrust.

→ Continue reading: The world in 1912 (according to the Times)

I suppose it’ll add some spice to history exams though. Get the wrong answer and you not only fail: you get carted off to jail as well.

– The concluding sentences of a piece by Mick Hartley criticising a new French law which, once President Sarkozy signs it, will make it a criminal offence to deny that genocide was committed by Ottoman Turks against Armenians.

Michael Jennings is now, as he recently said here that he would be, in Israel. Knowing my fondness for amusing multilingual signs, he today emailed me this photo, taken in Acre:

At first I thought that “Crusader” was some kind of business brand, although on second thoughts probably not. Maybe … actual crusader latrines? To clear up any doubt, Michael added:

It means exactly what it says.

Yes indeed, these are latrines which were once upon a time used by crusaders. And here, I presume, are those very latrines.

Don’t you just love the internet?

They said it would never be agreed. Then they said it would never be launched. Then they said it would fail. When it was a success, the euro-haters still insisted that the single currency was a recipe for economic chaos and political instability. The phobes are proving to be wrong again. At a time when so much of Europe’s political leadership is in flux, the single currency is the steadying point in an uncertain and worrying world.

Imagine that the recent turbulence on the continent had occurred when Europe still traded in pre-euro currencies. What would have happened to the French franc when neo-fascist Jean-Marie Le Pen forced the Prime Minister to quit? The franc would have plunged. What would have happened to the Dutch guilder when an anti-immigration party with a dead leader impelled itself into government? The guilder would have plunged too. Before a German election too close to call, even the stolid old mark would be gyrating. And instability in currency markets would be fuelling even more political chaos: a vicious, downward cycle.

That this has not happened is thanks to the euro. The single currency has taken all this political upheaval in its calm stride.

– From an anonymous editorial in the Observer headed “A tolerant euro”.

From 2002, in case you were wondering.

There is nothing in this film for the Left. Where they demonized Margaret Thatcher, the movie humanizes her. It is not about the great events of her political life; these are its backdrop. Her entry into Parliament, her leadership bid, the miners’ strike, the IRA and the Falklands War all feature, but the movie is not about them. Rather is it about the strength of character with which she confronted successive challenges and crises.

– Madsen Pirie reviews The Iron Lady. Unlike Nicholas Wapshott, Pirie liked it a lot, and says it will make those who see it like and admire the lady herself more.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|