We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

On the idle hill of summer,

Sleepy with the flow of streams,

Far I hear the steady drummer

Drumming like a noise in dreams

A. E. Housman

Now, in 1917 you might not be able to hear the drums but you might – depending on the proximity between your ear and the ground – be able to hear the drumfire:

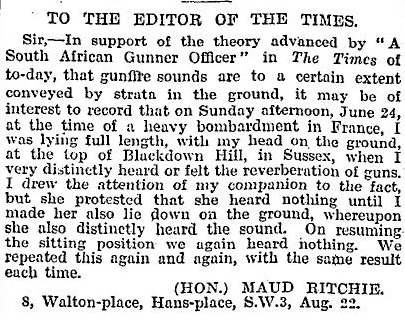

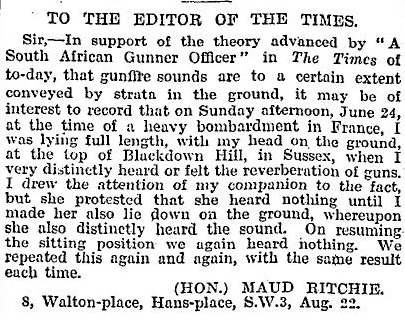

The Times 24 August 1917 p9. Right click for full article. Just in case you were wondering 24 June was in the “lull” between the Battle of Messines and the Third Battle of Ypres or Passchendaele as it is better known.

Things I know about Mother’s Day: correctly Mothering Sunday, early in the year, ancient celebration, all about being nice to mothers and appreciating their efforts.

Wrong.

Mother’s Day is not Mothering Sunday. Mothering Sunday is ancient. Mother’s Day is modern. And American. Mothering Sunday has nothing to do with mothers. Mother’s Day does. Mother’s Day only really came to be accepted (in Britain) in the 1950s when it got commercialised. Confusingly, the British have chosen to hold both celebrations on the same day.

The first modern (British) Mother’s Day was held on 8 August 1917.

I always had my doubts.

To the priests of ancient Egypt, the complexity of their writing system was an advantage. To be one of the few who understood the mystery of writing made a priest a powerful and valuable man.

This article, “The EU: Authoritarianism Through Complexity”, is by George Friedman who used to be chairman of Stratfor and now is chairman of a body called Geopolitical Futures.

Reading it made me think that the old term “priestcraft” might be due a revival:

The British team consists of well-educated and experienced civil servants. In claiming that this team is not up to the task of understanding the complexities of EU processes and regulations, the EU has made the strongest case possible against itself. If these people can’t readily grasp the principles binding Britain to the EU, then how can mere citizens understand them? And if the principles are beyond the grasp of the public, how can the public trust the institutions? We are not dealing here with the complex rules that allow France to violate rules on deficits but on the fundamental principles of the European Union and the rights and obligations – political, economic and moral – of citizens. If the EU operating system is too complex to be grasped by British negotiators, then who can grasp it?

The EU’s answer to this is that the Maastricht treaty, a long and complex document, can best be grasped by experts, particularly by those experts who make their living by being Maastricht treaty experts. These experts and the complex political entities that manage them don’t think they have done a bad job managing the European Union. In spite of the nearly decadelong economic catastrophe in Southern Europe, they are content with their work. In their minds, the fault generally lies with Southern Europe, not the EU; the upheaval in Europe triggered by EU-imposed immigration rules had to do with racist citizens, not the EU’s ineptness; and Brexit had to do with the inability of the British public to understand the benefits of the EU, not the fact that the benefits were unclear and the rules incomprehensible. The institutionalized self-satisfaction of the EU apparatus creates a mindset in which the member publics must live up to the EU’s expectations rather than the other way around.

The EU has become an authoritarian regime insisting that it is the defender of liberal democracy. There are many ways to strip people and governments of their self-determination. The way the EU has chosen is to create institutions whose mode of operation is opaque and whose authority cannot be easily understood. Under those circumstances, the claim to undefined authority exercised in an opaque manner becomes de facto authoritarianism – an authoritarianism built on complexity. It is a complexity so powerful that the British negotiating team is deemed to be unable to grasp the rules.

The ADC is a fire-eater and longs for the fray.

– Douglas Haig, Diary entry for 20 July 1917 commenting on a meeting with American Commander-in-Chief Pershing and other members of his staff.

And the name of this fire-eating ADC?

George S. Patton.

Professor Suzanne Fitzpatrick of Heriot-Watt university has written a quietly important article for the London School of Economics (LSE) blog: “Can homelessness happen to anyone? Don’t believe the hype”.

She writes,

The idea, then, that ‘we are all only two pay cheques away from homelessness’ is a seriously misleading statement. But some may say that the truth (or falsity) of such a statement is beside the point – it helps to get the public on board and aids fundraising. Maybe that’s true (I haven’t seen any evidence either way). But myths like these become dangerous when they are repeated so often that those who ought to, and need to, know better start to believe them. I have lost count of the number of times I have heard senior figures from government and the homelessness sector rehearse the ‘it could happen to any of us’ line. This has to be called out for the nonsense it is, so that we can move on to design the sort of effective, long-term preventative interventions in homelessness that recognise its predictable yet far from inevitable nature.

This caught my attention. A couple of years ago I wrote:

Yet it is possible to acknowledge the right of those put up these spikes to do so, and also have sympathy with the homeless. Ms Borromeo’s statement that “anyone, for any reason, could end up on the streets with no home” is the usual hyperbole (she need not worry about the chances of it happening to her), but it is true that things can go wrong for a person with surprising speed. There is probably at least one of your classmates from primary school who has lost everything, usually via drugs or alcohol.

And way before that, so far back that my blog post about it is lost in the waste of words, I had noticed well-meaning posters on the London Underground that stated that “wife-beating”, as it was then called, can happen to women of any class and any level of education. What is wrong with that? It is true, isn’t it? Undeniably, but “can happen” is very different from “equally likely to happen”, and if efforts to stop violence against women from their partners are equally spread across all demographics then fewer women will be helped than if resources are targeted to those most at risk.

Suzanne Fitzpatrick’s piece also gives another reason why framing the appeal in terms of “it can happen to anyone” is not a good idea:

On a slightly different note, the repetition of this falsehood seems to me to signal a profoundly depressing state of affairs i.e. that that we feel the need to endorse the morally dubious stance that something ‘bad’ like homelessness only matters if it could happen to you. Are we really ready to concede that social justice, or even simple compassion, no longer has any purchase in the public conscience? Moreover, it strikes me as a very odd corner for those of a progressive bent to deny the existence of structural inequalities, which is exactly what the ‘two paycheques’ argument does.

I might disagree with what seem to be Professor Fitzpatrick’s views on social justice and structural inequalities, but she is right about the morally dubious nature of the stance that “something ‘bad’ like homelessness only matters if it could happen to you”.

On similar grounds, I think it is a fool’s errand to try and promote a non-racial patriotism by claims that “Britain has always been a nation of immigrants” or by exaggerating the number of black people who lived here centuries ago. I am all for non-racial patriotism, but, sorry, no. The arrival of a few tens of thousands of Huguenots or Jews did not equate to the mass immigration of the last few decades. The migrations into Britain that were comparable in scale to that were invasions. And while there were certainly some “Aethiopians” and “blackamoores” living here in Tudor times, for instance, their numbers were so low that to most of the white inhabitants they were a wonder.

For those that know their history, to read the line “Britain has always been a nation of immigrants” promotes scorn. When those who at first did not know the facts finally find them out, their reaction is cynicism. Worse yet, this slogan suggests that love of country for a black or ethnic minority Briton should depend on irrelevancies such as whether the borders were continually porous through many centuries, or on whether people ethnically similar them happen to have been here since time immemorial. (The latter idea is another “very odd corner” for progressives to have painted themselves into.) If either of these claims turns out to be false, what then?

Better to learn from the example of the Huguenots and Jews. Whether any “people like them” had come before might be an interesting question for historians (and a complex one in the case of the Jews), but whatever the answer, they became British anyway.

The title of the piece by Rutger Bregman in today’s Guardian describes its main thrust well:

And just look at us now! Moore’s law clearly is the golden rule of private innovation, unbridled capitalism, and the invisible hand driving us to ever lofty heights. There’s no other explanation – right? Not quite.

For years, Moore’s law has been almost single-handedly upheld by a Dutch company – one that made it big thanks to massive subsidisation by the Dutch government. No, this is not a joke: the fundamental force behind the internet, the modern computer and the driverless car is a government beneficiary from “socialist” Holland.

and

Radical innovation, Mazzucato reveals, almost always starts with the government. Take the iPhone, the epitome of modern technological progress. Literally every single sliver of technology that makes the iPhone a smartphone instead of a stupidphone – internet, GPS, touchscreen, battery, hard drive, voice recognition – was developed by researchers on the government payroll.

Why, then, do nearly all the innovative companies of our times come from the US? The answer is simple. Because it is home to the biggest venture capitalist in the world: the government of the United States of America.

These days there is a widespread political belief that governments should only step in when markets “fail”. Yet, as Mazzucato convincingly demonstrates, government can actually generate whole new markets. Silicon Valley, if you look back, started out as subsidy central. “The true secret of the success of Silicon Valley, or of the bio- and nanotechnology sectors,” Mazzucato points out, “is that venture investors surfed on a big wave of government investments.”

Even the Guardian commentariat were not having that. The current most recommended comment comes from “Jabr”:

Whatever reasonable insights this article has (none of which are anything we haven’t heard before many times), they pale into insignificance compared to the one central and glaring fallacy, dishonesty, hypocrisy and absurdity at its core (and it’s remarkable that the writer seems oblivious to it): the writer is left wing. The specific branch of state activity where much US government innovation comes from is the federal armed forces of the United States, which every leftist hates more than anything. GPS wasn’t originally developed so we could find our way to the nearest organic kumquat shop – it was developed so that Uncle Sam could kill people more efficiently.

Thank goodness that leftists weren’t in charge of government investment decision-making at the time, because none of that investment would’ve been made and none of this technology would now exist – they’d have spent it on diversity coordinators and other progressive nonsense. Clicking on the writer’s profile, it says “The Case for a Universal Basic Income, Open Borders and a 15-hour Workweek.” So there we have it. I rest my case. That’s what society would’ve looked like, had the writer had his way – not a society which invested billions into military technology, but one which actively promotes indolence.

I would guess that most readers here will be closer to Jabr’s view than to Mr Bregman’s, but will not agree with either. But enough of my guesses as to what you think, what do you think?

In an earlier post I said that things were looking good for the Allies in late 1916. In essence, they were getting stronger and their enemies were getting weaker. In early 1917, things got even better. America joined the war while Russia became a republic with a democratic constitution. What could possibly go wrong?

Well, as we know, lots did. First, while America may have been a rich country with a large population it suffered from exactly the same problems as Britain did in 1914. Its army was small and not prepared for war against similarly-armed opponents. It would take time to become effective and it’s debatable whether it ever really did.

Second, the French launched the ill-fated Nivelle Offensive. Although it was far from a total failure, Nivelle had made extraordinary claims for it. When the hopes founded on these claims were dashed French morale collapsed. What happened to the French army at this time is still shrouded in mystery. The rumour is that far more French soldiers ended up getting shot for mutiny than was admitted at the time or even subsequently. It’s possible we’ll get to find out a little more this year when a few more of the archives are opened.

One of the odd things was how this affected Haig’s standing. In February, there had been an attempt to subordinate him to the French High Command. By May, the French government was asking his opinion on who should head that High Command. He didn’t give it.

Third, the February Revolution failed to stick. The Russian army had ceased to be an effective fighting force well before the Bolshevik take over in November.

So by late summer 1917 Britain’s only effective ally was Italy. While I am tempted to crack jokes Italian “effectiveness” the truth is that I don’t know enough about Italy’s contribution in the war to comment with any great authority. And, anyway, after the defeat at Caporetto, in November, they were in much the same position as the French.

Worse still, in February, the Germans launched unrestricted submarine warfare. This sent shock waves through the British high command. At one point, Jellicoe, the First Sea Lord, claimed that Britain had only a matter of months left before its food supplies ran out. The only thing that could save it was the British army capturing the Channel ports where most submarines were based.

This is the context in which Passchendaele – or the Third Battle of Ypres as it was officially known – was fought.

While we are on the subject of reminiscences… The moment they knew.

And here is the St Crispin’s Day speech from Henry V.

I loved the title of this autobiographical article by Tim Blair, describing how he came to turn away from the left wing views of his youth.*

Tell your personal stories of political evolution, in any direction.

*Basically he can’t keep his mouth shut.

Writing in the Kashmir Monitor, Alia P. Ahmed describes an aspect of Pakistan’s history whose effects still reverberate today:

When “Khuda” became “Allah”

In 1985 a curious thing happened: a prominent Pakistani talk-show host bid her audience farewell with the words Allah Hafiz. It was an awkward substitution. The Urdu word for goodbye was actually Khuda Hafiz (meaning God be with you), using the Persian word for God, Khuda, not the Arabic one, Allah. The new term was pushed on the populace in the midst of military dictator General Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization campaign of the late 1970s and 1980s, the extremes of which Pakistani society had never before witnessed. Zia overhauled large swathes of the Pakistan Penal Code to resemble Saudi-style justice, leaving human rights activists and religious minorities aghast. Even the national language, revered for its poetry, would not be spared. And yet, though bars and cabarets shut down overnight and women were told to cover up, it would take two decades for the stubborn Khuda to decisively die off, and let Allah reign.

She continues,

Today, Pakistan’s crisis of identity is chronic. A legacy of top-down cultural strangulation has left the national psyche utterly bewildered and deeply scarred. It has also given Pakistanis an inferiority complex – because we are South Asians and not Arabs, we are lesser Muslims. We must compensate. We must try our hardest to become Bakistanis.

Author Mohamed Hanif, in his celebrated debut novel, A Case of Exploding Mangoes, says it best: “…All God’s names were slowly deleted from the national memory as if a wind had swept the land and blown them away. Innocuous, intimate names: Persian Khuda which had always been handy for ghazal poets as it rhymed with most of the operative verbs; Rab, which poor people invoked in their hour of distress; Maula, which Sufis shouted in their hashish sessions. Allah had given Himself ninety-nine names. His people had improvised many more. But all these names slowly started to disappear: from official stationary, from Friday sermons, from newspaper editorials, from mothers’ prayers, from greeting cards, from official memos, from the lips of television quiz show hosts, from children’s storybooks, from lovers’ songs, from court orders, from habeas corpus applications, from inter-school debating competitions, from road inauguration speeches, from memorial services, from cricket players’ curses; even from beggars’ begging pleas.”

(Emphasis added – NS.)

The moment I saw this headline: Macron vows to renegotiate Calais treaty with Britain, I felt a frisson of excitement, and no doubt Mary Tudor’s ghostly inscribed heart started beating once again! Perhaps for the first time since January 8th, 1558, that splendid little town will soon be back under its rightful rulers.

Socialism has been tested out more times and in more variations than probably any other social system. It has been implemented in every continent, every culture, every stage of economic development. It has always led to disaster, to the extent it has been implemented. If you’re lucky, your country gets off with a mere economic crisis, as in Greece. At the worst, your country is in for decades of living hell.

– Robert Tracinski

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|