We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Tim Worstall has a new book out, Chasing Rainbows, which sets out what he regards as the economic fallacies of much of the Green movement. Such fallacies, he argues, actually get in the way of solving or at least trying to handle the genuine problems that may exist.

What is good about Tim’s book is that he is not some sort of cliched “denier”; he does not base his argument on the idea that AGW is some sort of evil collectivist con-trick or piece of doomsterish nonsense (although I am sure some commenters will want to raise that point). Rather, he says if there are problems caused by a buildup of CO2 in the atmosphere, and there are costs of such problems, then let’s use the tools of economics. For instance, he talks about carbon taxes. I am not a fan of taxes, but I can see a certain logic. They are far better than carbon credits and carbon trading, in my view.

Like Nigel Lawson, I see the idea of a market in carbon credits not as a solution to AGW but as something with great potential for fraud. The question I have about carbon tax, however, is what happens to the revenues. If they are levied by nation states, then clearly there will be demands for such taxes to be “harmonised” and levied by some sort of single organisation. And then the question arises as to what happens to such revenues?

Much of the book bears many of the trademarks of Tim Worstall’s own excellent blog: lots of data flecked with his caustic wit, often at the expense of such buffoons like George Monbiot and Jonathan Porritt, and on tax, the appalling Richard Murphy, who gets a solid going over at least once a day. There is a touch of PJ O’Rourke in how Tim likes to use a quip to make a serious point. I particularly like the way he gets hold of important concepts, such as the Law of Comparative Advantage, or the idea of opportunity costs, using examples of how forcing households to recycle waste imposes unpaid labour costs, which if added up, can be shown to represent a large cost. Being a good student of the great French classical liberal Frederick Bastiat, Tim understands the point about “what is seen and what is unseen” – understanding that the visible costs of environmental degradation need to be balanced against the unseen costs of trying to deal with it. Bastiat is one of those writers who ought, in a sane world, to be on the compulsory reading list of every school pupil.

The central message of this book is that there are problems, but there are also rational approaches to them, and that the Green movement, or at least its most collectivist parts, are blocking rational reforms. It is a similar point to that made by Matt Ridley in his book, the Rational Optimist, to which I have referred before. By their one-eyed focus on AGW alarmism, and by adopting a reactionary, command and control approach to the issue, they are blocking sensible alternatives, and also crowding out other issues, such as alleviation of poverty, which can be made worse by such foolish ventures as subsidies to biofuels, for example.

Chasing Rainbows makes for a good stocking filler this Christmas. Go on, do it for the children and for Tim’s bank balance.

I have been reading and enjoying Matt Ridley’s recently published book, The Rational Optimist, which shoots down a number of doomsterish ideas with great aplomb. For instance, he zaps the idea that we somehow reduce our “carbon footprint” by not importing foodstuffs from overseas. The international division of labour, he argues, is good for the planet, not harmful to it. The book is crammed with data to back up such points.

Ridley also has a blog based on the book, and it is worth bookmarking, in my view. Whatever his shortcomings as the former head of failed UK lender Northern Rock, Ridley is a fine writer and debunker of fashionable nonsense. More power to him.

I suppose that if someone asked me what is the subject that libertarians get into the most debates about with each other, I would probably say foreign policy (ie, should or would a libertarian polity even have a “policy” at all?); but then I might say that in second or third place would be intellectual property rights. It never fails to get the fur flying, metaphorically anyway. Here is an example of a fierce opponent of IP who is also an equally robust defender of property rights in everything else, at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, Stephen Kinsella.

My SQOTD a few days ago created a comment thread where IP came up. Now, I am not going to reprise the arguments for or against IP – here is a great essay by Tim Sandefur on the subject and here is another defending IP – but ask a slightly different type of question from readers, which is: what happens if state-created IP rights no longer existed? Could or would such things ever exist under any kind of Common Law system? How would new, potentially immensely useful ideas, come into being if folk could immediately copy them?

It is not good enough, I think, for a person to respond: “well, if writing books/making music/etc no longer pays, then take up bricklaying or perform live, or teach kids for a fee, or whatever.” I do not find such answers entirely satisfactory. In the age of the Information Economy, when so many people create value not by hard physical labour but increasingly, by manipulating ideas and concepts, it seems glib, to say the least, to shrug one’s shoulders about this.

So here are some ideas I have about what would happen. Remember, this post is not about my defending or attacking IP, but posing the question of what happens in a non-IP world, and whether we like the results:

More prize competitions to stimulate inventions, such as the Ansari X-Prize. Consistent libertarian opponents of IP should, of course, want the prize-winning funds to come from private donors and businesses, not the state. I happen to think that such prizes are a great way to foster innovation anyway.

Drugs: we might see a fall in the number of drugs being brought to market, if copying could be done. Bringing drugs to market is notoriously expensive; of course, libertarian anti-IPers might retort that a lot of the cost is caused by regulatory agencies such as the FDA in the US and their international counterparts, and they have a point; even so, reputable drug firms do not want to kill their patients, so trials and tests can take many years, even in a purely laissez faire environment. So we might have fewer drugs being sold and developed from what would otherwise be the case. We cannot measure this shortfall, but it seems a fairly reasonable guess that such inventions might decline. IP opponents need to address this, or at least state that this is a cost that “we” (whoever “we” are) are willing to pay. (This is a bit like the argument that getting rid of limited liability companies could harm, rather than help, economic growth but that the price is worth paying if we remove other problems allegedly connected to LL).

Contracts. Some firms, fearing that staff might defect and take blueprints of ideas to competitors, might insist on non-disclosure rules on staff in the event that they leave. This might actually lead to pretty draconian contracts being enforced in certain sectors, such as drugs and software, though not always easy to enforce in practice. Again, this would depend on the circumstances of individual firms, the sectors they are in, barriers to entry, etc. But some firms might be able to draw up such contracts particularly if the supply of labour for such jobs exceeded present supply.

Secrecy and concealment. Some firms, such as makers of radical new inventions, would go to far greater lengths to build them in such a way that the design was concealed, making it harder for people to get hold of the object, break it apart and reverse engineer it. It may still happen anyway, but firms might go to all kinds of ploys to try and make their stuff harder to copy, not always in ways we would like. Such efforts are a cost; again, is this a cost that outweighs the alleged negatives of IP?

And as a matter of practical reality, we might see some individuals get so enraged at having their ideas copied that this could get quite nasty. If a composer of a piece of music sees his score copied by someone who cannot even be bothered to acknowledge the source, and who performs it live and earns a fortune, then the composer might find out ways of seriously ruining the career of the performer, such as by libelling that person, blackmailing them, even physical violence. Do not forget that libel laws, for instance, are in part a way that the legal system tried to prevent folk killing each other in duels over affairs of honour. No-one likes the plagiarist, and opponents of IP need to accept that such conflicts might arise. I am not saying that the example of the irate composer would be justified in what he might do, but we are talking about likely outcomes, whether we approve of them or not.

One other consequence of a world without IP is that it makes enforcement of property rights in non-rivalrous stuff – such as land, movable goods – even more important in economic life than it is now. Property is inseparable from wealth creation, since if we cannot have the security of knowing that we can build up a store of wealth, then we cannot plan ahead and deal with our fellows in peaceful, voluntary ways. Good fences and good neighbours, and Englishmen in their castles, etc, etc.

Anyway, comment away. Play nice in the sand-box.

Singleton’s conclusion:

… it is not just fish where the EU is damaging us, but in financial services, manufacturing – indeed, its ever-increasing regulations impose unnecessary costs across the whole of our economy. Greenland, which retains free trade with the EU, shows that we can have the benefits of European exports, without the costs of its diktats. It’s surely time that we, too, said goodbye to Brussels.

Okay, cards on the table, Singleton is a sometime Samizdatista and a good friend of mine. But more pertinently, he is one of those free marketeers who is, unlike many of our breed, highly sensitive to mood, to atmospheres, to appearances, superficialities, surface trends, straws in the wind, stylistic nuances. He may not always be right about who is hot or who is cool (as opposed to merely who is right), but he is always thinking about such things. He is, after all, a paid journalist working for a major British broadsheet newspaper, who is trusted by that newspaper with editorial as well as writing responsibilities. When he writes stuff, he is typically wearing a suit. He is, in other words, the exact opposite of your typical old grump UKIPer. The significance of this piece of his about Greenland and the EU is not just in what it says, but in its timing. If Singleton reckons that now is a good time to be saying such things, that says something to me, as in something else besides what he is actually saying.

As still current Samizdatista Johnathan Pearce has often said here in recent months, especially in comments, something important just might be stirring in little old Blighty. It’s as if “we”, whoever exactly we are, have been sitting on our hands, waiting for Gordon Brown to depart, and then waiting to see how David Cameron would turn out (given that his mere words communicate so very little). Now we are beginning to learn, and now we are beginning to find our voices and to exert some actual pressure.

I rather like this habit of economists trying to put their own money on the line in making certain predictions. David Henderson has an item about it. It adds a certain frisson to the joustings between different camps. The most famous bet of all, of course, is the one between the late Julian L Simon and Paul Ehrlich. The latter lost his bet that the price of commodities would rise over a certain period (they did not) and he declined to accept another bet for another decade. Poor loser, I say.

I would have liked to have seen the odds back in 2008 that Obama would likely be only a one-term president, or that one, or possibly two, nations could be driven from the euro-zone by say, 2011/12.

Indeed.

The thing about Delingpole is not just the things he says, but the huge numbers of people he says them to, throughout not just the UK but the entire anglosphere. He said “climate science” was hooey to his massed readership, when saying that really counted for something. Now he is arguing for serious cuts, as in actual reductions, as in large reductions, in government spending, here in the UK, in the USA, and pretty much everywhere, at a time when that too needs to be said very loudly.

It is an odd feeling watching all the things I have have been banging on about for the last third of a century or so – about taxation, spending cuts, Hong Kong, the Asian Tigers, etc. – being banged on about by someone half my age and of several times my eloquence. Extreme jealousy mixed with extreme delight about sums it up. The former, I am getting over. The latter will last. I can remember when we used to dream of getting stuff like his in the Telegraph … blah blah.

So, well done Delingpole, and keep it coming.

I left this comment over on Tim Worstall’s blog yesterday, and I thought I might reproduce it here:

“While it is undoubtedly true that there are barriers to entry in certain fields that give the incumbent management the kind of “rent-seeking” powers you talk about, it strikes me that shareholders, over the long run, are hardly likely to tolerate payouts of massive salaries for crummy investment returns. Ironically, it is precisely the sort of mercantilist policies that the left supports – such as attempts to restrict foreign takeovers of “national champions” – that shield management from competition and hence, breed complacency.”

“There is a genuine, global market for talent, and in this globalised, increasingly fiercely competitive world, the pay for the top people will be high. Sure, we can and should remove barriers to entry, and one obvious way to do that would be to encourage small businesses to grow fast and challenge the supposed hegemony of Big Business; this means more free trade, not less; it means fewer regulations and lower, flatter taxes, not more of them, and so on.”

“In other words, if high pay for supposedly underperforming CEOs riles you, then we need more capitalism, not the sort of statist ideas propogated by the likes of Compass.”

For those who may not know, Compass is a leftist pressure group in the UK that tends to argue for such clever ideas as higher taxes, ever greater regulation of business, and so on.

Dr. Bernanke unfortunately does not understand economics, he does not understand currencies, he does not understand finance. All he understands is printing money. His whole intellectual career has been based on the study of printing money. Give the guy a printing press, he’s going to run it as fast as he can.

– Jim Rogers, investor and commentator, giving his considered view on Ben Bernanke, the current chairman of the Federal Reserve.

Too bad there already is an SQoTD for today, but here’s a classic bit I’ll copy and past for you anyway:

We are almost getting to the situation where we will be seeing unemployed environmentalists walking the streets. As with unemployed actors who describe themselves as “between jobs”, one might expect them to admit to being “between scares”.

That’s the EU Referendum man, Richard North, ruminating about how the environmental debate is now going quiet, and about how the forces of darkness are now going to have to find themselves a different line of bullshit to work with. “Biodiversity” won’t nearly suffice. How true. Although, as he’d be the first to remind us (I found that link in this), “climate” money is still being thrown around like there’s no tomorrow, and if that carries on there probably won’t be. Anyway … as I was saying. Between scares.

That phrase could really get around. It deserves to.

I know we keep banging on here about Steve Baker MP, but he really is excellent.

The thing about Baker is that he doesn’t just say the uncompromisingly libertarian things that he does say about economics and economic policy, and about, to quote the title of his talk, honest money and the future of banking. He is willing to be immortalised on video saying them, and therefore potentially to be heard saying them everywhere on earth. Amazing. Truly amazing.

This performance lasts just over forty minutes. I urge you to make the time to look at it and listen to it. If, like me, you have any sort of drum handy, I also urge you to do some banging on about it yourself.

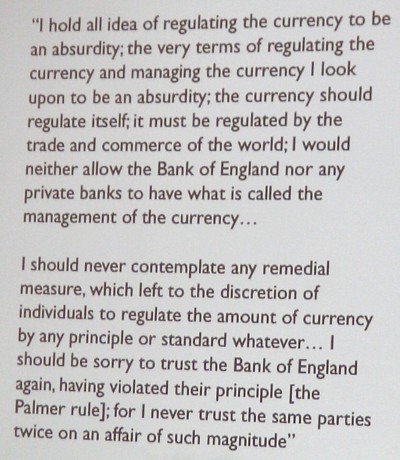

– Richard Cobden (1804-1865), quoted at the Cobden Centre website. Quoted again by Steven Baker MP at the end of his presentation this morning to the Libertarian Alliance, and featured in his final slide, of which the above is my somewhat wonky photo.

Here:

In a fascinating 36 minute interview, Cobden Centre Radio’s very own Brian Micklethwait speaks to James Tyler, the Chief Executive of Tyler Capital and a member of our Cobden Centre advisory board.

I’ll surely have more to say about this, but busy day today. So suffice it to say, for now, click on this to listen to the mp3, or follow the top link to find it as a podcast.

My main general impression of James Tyler was what a good and thoughtful person he is, very much his own man in how he thinks about things and goes about things, yet in no way scornful of or unsympathetic towards others who take the road more travelled. If the propaganda fence to be got over is that Austrian economics, once you’ve been told about it by your resident lefty, is an excuse for billionaires to piss on everyone, then a man like Tyler is just the sort to get you thinking that it’s a whole lot better and more intelligent than that.

His central point was that nobody should have the kind of power over economic life that our current powers that be (“crony capitalism”) do now have.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|