We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

The pessimism expressed here for some time about China is now being expressed more widely.

Yesterday, via one of my favourite blogs, that of Mick Hartley (I especially like Hartley’s own photos), I found my way to some other photos by David Gray, of China and its newly minted ruins of the last decade and more. My favourite of these is the very first in the set displayed at the end of that link, which has what it takes to become “the” Chinese picture for right now.

It looks very impressive from a distance …

… but if you look at it closer up, it turns out to be a structure constructed by an idiot, full of steel and concrete, accomplishing nothing.

A few weeks ago, Samizdata’s travel and much else besides correspondent Michael Jennings, who has (of course) recently been in China (he has recently been everywhere), was talking of doing a piece about the mad building spree now, still, going on in China. I’d still love to read such a piece, but I fear that Michael may have missed that particular boat, in terms of revealing anything very shocking.

Happily, he did comment at length on an earlier short Samizdata posting about the Chinese construction bubble.

“All corporate taxes fall on households in the end. Companies might be convenient places to get cash from but they are not the people actually carrying the economic burden. It is some combination of shareholders, workers and consumers that are carrying the burden: those getting the social services which they are unable to fund.”

– Tim Worstall, dealing with yet another piece of nonsense from that over-blown socialist buffoon, Richard Murphy. I have to admire Tim’s stamina in how he relentlessly mocks and refutes the rubbish from Murphy. But someone has to do it.

This afternoon I visited the office of The Real Asset Co, and talked with Ralph Hazell (CEO), William Bancroft (Head of operations), and Jan Skoyles (Economist). I have hardly begun to digest the lessons I learned from what they told me. But in the meantime, let me at least supply a link to this video interview that Jan Skoyles did with Steve Baker MP, our favourite politician by some distance here at Samizdata. Jan Skoyles is living proof that you can earn a living as an “economist” without knowing an enormous pile of things which are not so.

More and more, I find myself fearing that Baker is just too good to be true, and that some frightful skeleton will one day soon come tumbling out of his closet. I have absolutely no rational basis for such fears. It is just that the man is a politician.

I recall sitting next to Baker at a Cobden Centre dinner about a year ago, and rather rudely telling him that I expect from him: absolutely nothing, on account of him being a politician. He has already far surpassed my wildest fantasies. This video interview once again had me blinking in disbelief at the sheer uncompromising sensibleness of what he was saying. I did take a nap earlier this evening. Was I dreaming again? Apparently not.

This afternoon I attended an event in the House of Commons organised by the Adam Smith Institute, to launch their publication (published in partnership with the Cobden Centre) entitled The Law of Opposites: Illusory profits in the financial sector, by Gordon Kerr. Kerr himself spoke.

Alas, Gordon Kerr is a rather quiet speaker, and he did not use a microphone. Worse, after the talk had begun, I realised that right there next to me was some kind of air conditioning machine whirring away, in a way that made following Kerr’s talk difficult. Live and learn.

But I got the rough idea. Bad accountancy rules make disastrously unprofitable banks seem like triumphantly profitable banks, and those presiding over these banks are paid accordingly, even as their banks crash around them. And much more. The ASI’s Blog Editor offers further detail.

Good news though. I, like everyone else present, was given a free copy of The Law of Opposites. See if you can spot why I am reproducing the cover here. I am sure this will not take you long. I was interested to see if the effect in question would survive my rather primitive scanning skills. It does:

This publication is quite short, less than a hundred pages in length. Even better news. You don’t have to buy a paper copy like the one I now possess if you don’t want to. You can read the whole thing on line.

I am on the Cobden Centre email list, and I have to be careful about confidentiality with regard to many of the emails I read. However, the one I just got today from Jamie Whyte is presumably intended to get around:

I’m on BBC’s Radio 4’s PM programme tonight, discussing the report on the FSA’s failure to notice that RBS was about to fail – up against some former official of the FSA. I am afraid they are going to edit what I said (fingers crossed on that) and also that I cannot tell you the exact time my item will come on the programme, which starts at 5pm, I think.

The FSA is the British financial regulator. RBS is the Royal Bank of Scotland. According to the man from the FSA, the Royal Bank of Scotland’s woes were caused by poor decisions.

I’m guessing that Jamie Whyte will be a bit more informative than that. I am out and about this evening, but it looks like there’ll be a recording available, for a while. If nothing else, this is further evidence that the Cobden Centre gang are putting themselves about.

LATER: I managed to listen to Jamie Whyte’s performance, and better, to record it. Here is what he said in his opening statement:

[The FSA] did fail. But I don’t blame it on the individuals of the FSA. I think that they have an impossible task. What’s happened in banking is that because of government guarantees to those people who lend money to banks, explicitly in the case of retail depositors – you and me with our ordinary money in the bank, and implicitly and pretty reliably in the case of wholesale lenders to banks, because they’re government guaranteed, there is no price mechanism any longer in the banking market for risk. So banks can take as much risk as they like and without paying a price for it. Normally what would happen in a free market is that it would become more expensive for banks to borrow money. And that doesn’t happen. There’s no risk premium for banks taking larger risks, because the people lending the money realise that the government will bail them out.

Now the effect of this is that basically the government is subsidising bank risk taking on a massive scale. And the job of the FSA is to counteract that. There are these rules – the Basel rules and so on about capital requirements. And then there are supervisors, regulators, people who go into the banks and check they’re complying, and their job is to counteract the massive incentive towards risk taking that the government has already provided. Now the question is: can they do it? They obviously failed to do it. Can they, if they do a better job? And I think they can’t.

And the reason they can’t is that there are almost infinitely many ways that banks can take risks. The rules will always specify some particular ways, and regulators will go in, looking at that stuff. Are they doing this or that? But the bankers are very clever and they can always come up with other ways of taking risks, and I just think it’s a hopeless task that they’ve been given.

Whyte’s opponent in the debate, a Mr Jackson, got off on the wrong foot at the start of his reply:

I think it’s very easy to blame the regulators.

Which many are indeed doing, but not Jamie Whyte. His point was that their task is impossible.

Mr Jackson went on to say that he thought that the regulators could do better, by, you know, doing better. And the BBC gave him the last word. Which was him saying that the regulators could indeed … do better.

But Jackson never really said why he thought this. There was talk of cats and mice, and of how the mice are very numerous and very incentivised and the cats unable to cope. The general idea was aired of making regulators less numerous, better paid and above all “better trained”, and of having these few regulatory titans apply only one simple all-embracing regulation, rather than lots of regulations (with lots of omissions), namely: Banks must behave well! Putting the regulators entirely in charge of banking, basically, although that was not quite spelt out. It was classic Road to Serfdom stroke Economic Calculation stuff, with one guy saying that calculation is screwed and should be unscrewed by the state retreating rather than advancing, and the other guy saying: we can still regulate better in the future (despite the evidence of the recent past), by making the arbitrary power of the state even more arbitrary and even more powerful (and hence even more likely to screw things up on an even grander scale in the future).

Just who “won” this argument is anybody’s bet. I think that Whyte made a much stronger case than his opponent, but I would, wouldn’t I?

More to the point, anyone generally inclined to favour free markets, capitalism, etc., to favour rational economic calculation and to oppose serfdom, would definitely have scored it a win for Whyte on points. Such a person might even want to dig further into the argument with some internet searching. At which point the fact that Whyte is spelt with a “y”, and that Whyte was introduced only as a “financial commentator” (rather than being from, say, the Cobden Centre) won’t have helped any.

Perhaps this posting will help such searchers after truth rather more.

I cannot claim to grasp much of the detail of all the drama now surrounding the EUro. This photo, taken by me yesterday, captures the feeling of it all quite well:

Click to get that bigger and more legible.

Is all this drama being cranked up to enable Cameron to take the credit from us Brits for bollocking up the Euro, and simultaneously to enable everyone else in EUrope to blame us? Just, as Americans say, askin’.

One little titbit of news that does strike me as particularly interesting is this, in the Wall Street Journal, about how various governments are quietly pondering EUro-alternatives. At the very least, someone at the Wall Street Journal is asking about alternatives.

It all makes me think of those bridges that Julius Caesar burned, so that his army then knew that they would either fight and win, or perish. Except that this time, various parts of the army are nipping back to the various rivers that they just might be wanting soon to be retreating across, and are quietly building bridges. Just as burning bridges changes the game, so does building them. Even thinking about building them changes things.

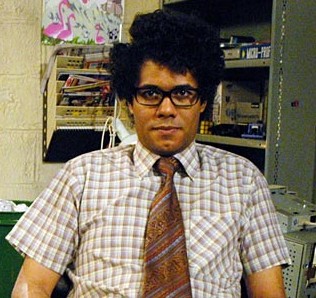

I greatly enjoyed this article by Kevin D. Williamson about Thomas Sowell. Sowell is now in his eighties. When somewhat younger, he looked like this:

Here is what is probably the key paragraph in Williamson’s Sowell piece:

Because he is black, his opinions about race are controversial. If he were white, they probably would be unpublishable. This is a rare case in which we are all beneficiaries of American racial hypocrisy. That he works in the special bubble of permissiveness extended by the liberal establishment to some conservatives who are black (in exchange for their being regarded as inauthentic, self-loathing, soulless race traitors) must be maddening to Sowell, even more so than it is for other notable black conservatives. It is plain that the core of his identity, his heart of hearts, is not that of a man who is black. It is that of a man who knows a whole lot more about things than you do and is intent on setting you straight, at length if necessary, if you’d only listen. Take a look at those glasses, that awkward grin, those sweater-vests, and consider his deep interest in Albert Einstein and other geniuses: Thomas Sowell is less an African American than a Nerd American.

My strong is Williamson’s italics.

I’d never thought of Sowell as being anything like this guy …

But yes, I guess maybe there is a resemblance. Here is link to a brief snatch of video of Moss saying something very Sowellish, about the importance of getting a good education.

By the way, I am not calling the actor and director Richard Ayoade a nerd. I don’t know about that. But I do know, as do all who enjoy The IT Crowd, that Ayoade’s TV creation, Moss, most definitely is a nerd, and a nerd first and a black man way down the list, just as Williamson says of Sowell.

Although, as a commenter said of this bit of video: “Richard has a bit of Moss in him.” A bit, yes. But what has really happened is, surely, that Ayoade was a nerdy kid, and has kept hold of it for comic purposes.

I suspect Sowell did something similar, and, as Williamson suggests in his article, in a more courageous and significant way. He too was a genuinely nerdy kid, who could understand truth better than he understood the demands of fashion. Then, when he got older and started to tune into the zeitgeist, he had to decide if he was going to shape up and get with the liberal (in the American sense) fashions of his time or stick with that truth stuff he had got to like so much. He stuck with the truth.

Also, I don’t believe Sowell would ever remove a water tank (see the second of the two video links above) and then be surprised that his plumbing no longer worked properly.

By the end, we may see profligate politicians hanging from lampposts. But there’ll be a lot of bad stuff, too.

– Instapundit

LATER:

But all joking aside, if the current profligacy continues, and America winds up in a Greece-style (or worse) collapse, politicians may not wind up hanging from lampposts (we don’t really do that here), but they will at the very least likely face the kind of investigations, prosecutions, and social opprobrium normally reserved for child molesters and Bernie Madoff types. I don’t think they fully appreciate that. If they did, they’d be acting differently.

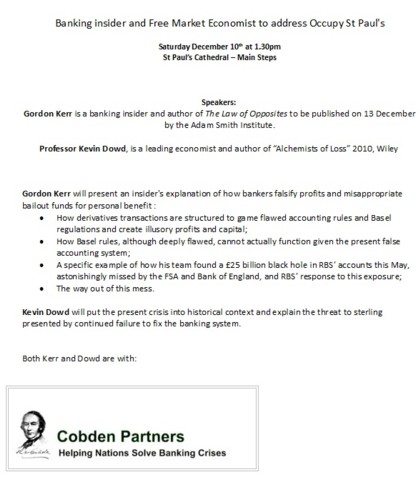

Indeed. Press release from these guys:

Good luck with that.

Seriously, good luck with that.

I will try to be there.

Legitimately self-made African billionaires are harbingers of hope. Though few in number, they are growing more common. They exemplify how far Africa has come and give reason to believe that its recent high growth rates may continue. The politics of the continent’s Mediterranean shore may have dominated headlines this year, but the new boom south of the Sahara will affect more lives.

From Ghana in the west to Mozambique in the south, Africa’s economies are consistently growing faster than those of almost any other region of the world. At least half a dozen have expanded by more than 6 per cent a year for six or more years.

The Economist, 3 December, page 77. (Behind the magazine’s paywall, so thank me for typing it out for you). The magazine has a nice study of the continent, laying out the continued problems but also the many bright spots. There is a handy map showing which countries have the fastest and slowest GDP growth rates, with the fastest rates in black (Ethiopia, at 7.5 per cent), then red, lighter red, all the way down to the deadbeats, in white. Of course, in looking at percentage rises or falls in growth, it pays to remember that statistics can be highly misleading (hardly a surprise to any skeptics of government, of course) and it is easy to rise fast from a low base. But still, these numbers are indicative of a more positive picture.

Needless top say, Zimbabwe came at the bottom of the growth league. It remains a grim lesson in how collectivism, cronyism and debauchery of money spell disaster. If parts of Africa are beginning to understand the follies of this and start to make serious money, that is excellent news. For a start, refugees from the hellholes of the continent might, instead of entering sclerotic Europe, choose to make a life in a more congenial place elsewhere.

Of course, there have been false dawns before. But with the flood of money entering the continent from China (after all that commodity wealth), I have a feeling that the rise of Africa has some staying power, particularly given the young demographics. Of course, it could all be messed up from things such as a rise of global protectionism.

There is something about this story about bank debt buybacks that I don’t quite understand, although I have only had two cups of coffee as of the time of writing:

“European banks are turning to buying back their own debt in order to raise some of the billions in extra capital required by regulators. At least six major banks have launched debt buybacks in the last two weeks and investment bankers say more are likely.”

Okay, so if a bank has debt – ie, others are lending it money – and the bank buys back, or in other words, pays off some of that debt, like paying off a credit card, say, how is this raising capital? The bank is presumably paying the debt off with, er, what? Fairy dust?

“In Lloyds’ case, it will exchange bonds previously issued for new instruments that are compatible with new regulations. The move allows lenders to book profits and reduce the stock of non Basel III capital on their books without issuing new equity or offloading assets.”

This is not very clear. What is the defining characteristic of “Basel III capital” in this case?

Finally we get a glimmer of how this actually works:

“The capital raised in this way is likely to be in the hundreds of millions. It boosts earnings by realising “own credit” gains that are otherwise purely theoretical. The market price of banks’ debt has fallen dramatically in recent weeks, which enables banks to buy back their debt for an amount above the market price but below the cash they raised by selling the instruments, booking a profit.”

Now I understand – I think.

As usual, the CityAM publication has a blisteringly good item on the Eurozone’s latest absurdities today. It is become my daily morning read. The fact that several of its writers are friends and acquaintances is, of course, purely coincidental.

Incoming email from newly signed up Samizdatista Rob Fisher (who can only do emails right now) about how Oxfam is proposing a global shipping tax. Watts Up With That? has the story.

Says Rob:

This is extraordinary. Read the whole thing but in particular the money flowchart diagram.

Bishop Hill calls this Oxfam creating famine.

Says Anthony Watts:

These people have no business writing tax law proposals, especially when it appears part of the larder goes back to them. This is so wrong on so many levels.

Says Bishop Hill commenter ScientistForTruth:

These [snip – please tone down the language] are in principle no different from the pirates operating out of Somalia, wanting to skive money off international shipping. And just as Oxfam would be solicitous to ensure that no-one gets their hands on the dosh unless they sign up to an eco-fascist agenda, so the pirates will be sure to share the booty only with their mates.

I do enjoy those Bishop’s Gaff Bishop’s Rules bits in his comments section. Perhaps “what a bunch of total snips” will catch on as an insult.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|