We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Here is a list of things that you can buy, but which Michael Sandel (who I seem to recall doing a series of lectures for the BBC – yes) thinks it’s morally dubious for you to be able to buy.

I haven’t read all of them, but was immediately struck by this one, which strikes me as, on the face of it, a very good idea:

The right to shoot an endangered black rhino: $250,000. South Africa has begun letting some ranchers sell hunters the right to kill a limited number of rhinos, to give the ranchers an incentive to raise and protect the endangered species.

To Michael Sandel, this seems to mean that South Africa is being bad. But to me it sounds like South Africa is serious about preserving its now endangered black rhinos.

I have a definite recollection of noted South African libertarian Leon Louw having recommended just such a thing. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to learn that he was partly responsible for this arrangement.

I myself won’t comment in detail on the rest of Sandel’s piece. It is complicated and I am about to go to bed. Parts of what he says strike me as true, parts not. But me saying only that needn’t stop other commenters going into more detail.

Spring is in the air, and there is a spring in the step of the climate skeptic blogs these days, the two big ones on my radar being Bishop Hill and Watts Up With That. Peter Gleick‘s trickery, already written about here by Natalie Solent, combined with the willingness of so many on his team to try to promote him as some kind of hero rather than condemn him as the failed fraudster that he is (see also this posting about Michael Mann), means that although climate skepticism hasn’t won, it continues to win. Slowly but surely, C(atastrophic) A(thropogenic) G(lobal) W(arming) is being reduced from “science” to a racket.

Declarations of complete victory are surely premature. Much depends on how you define victory, and who or what you consider to be the enemy. If you care only about scientific truth, but not about the world being littered with damaging and expensive bureaucracies dedicated to perpetuating and enforcing lies, you may well indeed believe this battle to be nearly over. If those bureaucracies (to say nothing of the larger financial and ideological interests they serve) still trouble you, as they do me, you will regard the war as hardly having begun.

Some are saying that continuing to argue about the mere science of it all is a distraction from the more serious task of unmasking the motives and machinations of all those personages to whom all this fraudulent science has been so useful. I disagree. I say that showing this “science” to be dishonest leads naturally on to the question of who patronised it and to what end, given that the mere truth of things was emphatically not the only thing that concerns all those concerned. If the science of CAGW was now, still, universally accepted as honest, the underlying intentions of the various factions and characters responsible for foisting it upon the world would not now be attracting nearly so much scrutiny.

An immediate next task for the skeptic tendency is to itemise and publicise, in greater detail than hitherto, who is making money out of CAGW, a process that is already well under way. The longer term goal is to unmask the politics of it all. The bigger goal behind this hoax (and many others) was, and remains, to turn the entire world into a corrupt tax-and-spend superstate, run for the pleasure and enrichment of anti-progress, screw-the-poor-in-the-name-of-the-poor, global despots. That many very useful and desperately sincere – very useful because so desperately sincere – idiots are and always have been involved in this project is not in question. These idiots need to be challenged intellectually rather than merely denounced as crooks and tyrants, although showing them that crooks and tyrants is who they are really supplying aid and comfort to may also help to straighten them out.

In the post, and I should have read this book months ago: Watermelons. James Delingpole has been a key figure in ensuring that the CAGW ruckus (and the Climategate story in particular) escaped from the ghetto of blogs like the ones I linked to above, into the general arena of political discussion, and even to infect parts of the general public, now so curious to know why their heating bills are going ballistic. The thing about Delingpole is that not only has he done a fine job publicising the various scientific criticisms of the CAGW faith. He also understands what set the whole thing in motion in the first place. He gets the money of it. Above all, he gets the politics of it. When I have read this book, I’ll surely want to say more about it here.

Charlie Stross writes great science fiction and a blog which usually leaves me wondering how I can enjoy so much the novels of a man with whom I agree so little. In a recent post he linked to an article by UCSD associate professor of physics Tom Murphy to explain why space colonisation will not happen. Since the site is called “Do the Math” I was expecting some numerical analysis of space colonisation. Instead the article contains lots of reasons why space travel is hard and slow and requires lots of energy and is not likely to be done much more by NASA, but nothing that suggests it violates the laws of physics.

I like physicists. They do real science that gets answers from proper observations. So I was a bit disappointed by the space article and went in search of goodness. There must be some good insight that a physicist like Murphy can offer.

He analyses the growth of energy consumption. Since 1650, total energy usage of the United States has increased by about a factor of 10 every 100 years. If energy production continues to accelerate at this rate, we’ll heat the atmosphere to 100C in 450 years. Murphy is not saying this will happen, he is saying that there is a limit to how much energy we will want to produce. So far so good. But how much energy can a person use? Why does it matter?

Once we appreciate that physical growth must one day cease (or reverse), we can come to realize that all economic growth must similarly end. This last point may be hard to swallow, given our ability to innovate, improve efficiency, etc. But this topic will be put off for another post.

So this is to be a Limits To Growth argument. In this other post Murphy talks a lot about the limits to how energy efficient things can be. He is right that it will always take a certain amount of energy to heat food, for example, and that there are processes that can not be improved beyond physical limits. But he seems unable to imagine economic growth without growing use of energy. Doing the same task with half the energy, something that is a routine advance in computing technology, is economic growth. Murphy admits this, but gets hung up on the fact that these other things can not improve. This is a problem, because

As long as these physically-bounded activities comprise a finite portion of our portfolio, no amount of gadget refinement will allow indefinite economic growth. If it did, eventually economic activity would be wholly dominated by us “servicing” each other, and not the physical “stuff.”

To which I say: what is wrong with that? Here is what Murphy thinks is wrong with that, and here we get to what may be his fundamental error:

The important result is that trying to maintain a growth economy in a world of tapering raw energy growth (perhaps accompanied by leveling population) and diminishing gains from efficiency improvements would require the “other” category of activity to eventually dominate the economy. This would mean that an increasingly small fraction of economic activity would depend heavily on energy, so that food production, manufacturing, transportation, etc. would be relegated to economic insignificance. Activities like selling and buying existing houses, financial transactions, innovations (including new ways to move money around), fashion, and psychotherapy will be effectively all that’s left. Consequently, the price of food, energy, and manufacturing would drop to negligible levels relative to the fluffy stuff. And is this realistic—that a vital resource at its physical limit gets arbitrarily cheap? Bizarre.

This scenario has many problems. For instance, if food production shrinks to 1% of our economy, while staying at a comparable absolute scale as it is today (we must eat, after all), then food is effectively very cheap relative to the paychecks that let us enjoy the fruits of the broader economy. This would mean that farmers’ wages would sink far lower than they are today relative to other members of society, so they could not enjoy the innovations and improvements the rest of us can pay for.

The first paragraph simply lacks imagination, but the second one is almost unforgivable. Food production has already gone from being nearly 100% of the economy to a much smaller proportion of it. Are farmers poorer as a result? Of course not. There are fewer of them and each one produces food for more people. This is how food has got cheaper in the first place. A human body needs 100 Watts to work. We could completely automate food production using some multiple of 100 Watts per person which is only a small proportion of each person’s energy budget, and there is your almost free food. With this kind of material abundance economic activity can be completely intellectual, no problem at all.

Can growth continue forever after that? It is possible that we will hit some limit of how much computation, and therefore intellectual activity, can be done with the available energy. Ray Kurzweil has tried to calculate the physical limits of computation and his answers are in units of how many entire civilisations can be simulated per second. So the limits are quite high.

This is Murphy’s other error. He writes, “I am unsettled by my growing concerns about the viability of our future”. In response to these concerns he proposes abandoning growth, not having kids and not eating meat. But he has gone the wrong way. He calculates that there are limits and is afraid of attempting to reach them. If you flip the argument around, what physics tells us is just how much wealth is possible. I have already described how material abundance can be had for very little energy. There is plenty of energy for a much larger population to live a much longer life with no material concerns and as much entertainment and intellectual stimulation as a person could want. Perhaps Murphy knows this, and it is the source of his cognitive dissonance when he writes, “such worrying is not consistent with who I am.”

…to the UK’s anti-capitalist left in a truly splendid rant:

The callous capitalist west is happy to house you if you want to be housed. It will educate for free from 3 to18 years. It will attend to your medical needs, cradle to grave, regardless of what you do to your own body. It agrees to protect you from hostile countries with a military and from hostile fellow citizens with a police force, whether or not you yourself are a criminal. If you catch on fire it will send someone round to put you out. It will have a justice system to ensure you are fairly treated and will provide a lawyer for you if you need one.

The state doesn’t care what religion you are. What you call yourself. What you wear or where you travel. The state will provide infrastructure every citizen may use regardless of how much taxation that individual has contributed to its development. Anyone may use terminal 5 or New Street station or the M25. It will give you money every week and ask only that you sign for it once every month. More money if you’re ill. Or if its cold.

When you’re sixty five or sixty eight it will give you more money if you have never saved or earned any any of your own.

It won’t even ask you what you’re doing with the cash. It will let you spend it on cigarettes, booze, Cheesy Whatsits, gambling or an E Harmony subscription. The state doesn’t care.

It won’t demand you serve in the military or a national service labour scheme. It doesn’t even ask you to give blood or take part in medical experiments. Or sweep up the streets or even just sign an agreement that you promise only to say nice things about the government.

And that’s just a democratic government. Capitalism adds choice. Technology. Medical advances. Communications. Longevity. Energy. Transportation. Travel. Comfort.

The whole of civilisation has been a struggle to secure enough food to eat and enough shelter to survive.

That’s the argument. The last line stands on its own: what the Wolf-Klein-Monbiot corner sees as the wicked selfishness of trade and the terrible vulgarity occaisioned by choice and freedom, are medicine, not sickness. Read the whole thing here. (H-T: Worstall)

We are often told, even by so-called “left libertarians” who claim to be in favour of markets but not corporatism, that modern corporations, with their evil limited liability protections, favours from the state and so on, can roll over a democratic government and shaft the general public. Up to a point, Lord Copper. In fact, the situation is far more complicated. Some firms seem remarkably weak when confronted with some pressures, which makes me wonder why Hollywood movies still insist on portraying corporate executives as flinty-eyed, heartless bastards on the take. (The irony is, of course, that some of the most ruthless corporations are in the film business).

As evidence, Brendan O’Neill has this excellent piece in the Telegraph about Tesco’s, workfare, and the influence of the “Twitterati”:

“What could be worse than the government’s workfare programme?”, almost every columnist in the land is currently asking. I can think of one thing worse: the awesome and terrifying power of the commentariat and its slavish groupies amongst the Twitterati to strike down initiatives like workfare and almost any other government project that they don’t like. That’s the real story here. Forget the historically illiterate wailing about young people being forced into “slave labour” or the idea that getting yoof to work in return for money is the Worst Thing Ever. The ins and outs of workfare itself pale into insignificance when compared with the new power of tiny cliques of cut-off people to override public opinion and reshape modern Britain.

The speed with which first Tesco, that supposedly arrogant monolith of the high street, and then others withdrew from the workfare scheme was alarming. It was a testament both to the sheepishness of modern corporations (remember this next time someone starts banging on about “free-market fundamentalism”) and to the authority of the therapeutic, suspicious-of-wealth, pro-state, anti-big-business sections of the well-fed media classes, who can now put powerful institutions on the spot simply by penning a few ill-thought-through articles with the word “SLAVE” in them.

One possible quibble: has this not been the case for decades, even centuries? Consider that the opinion-forming classes have tended to be concentrated in the London area, have tended to have an influence out of all proportion to their numbers? This is hardly new. What has changed, clearly, is that in the age of the internet, the speed with which this class can make its voice heard accelerates.

I always thought it was a bit optimistic to imagine that blogging, the internet and so on would massively shift the balance of forces in terms of who gets to influence debate in a country like the UK. The mainstream media still carries big influence, especially television. And our political class, drawn as it is from a relatively shallow pool of talent, is as susceptible to the influence of such opinions as it ever was. However, what I think has changed for the better is that more of us, such as O’Neill and so on, can attack the conventional wisdom through the medium of the internet rather than hope that our letters get printed in some corner of a newspaper.

There is also more of what we might call a “swarm effect” these days with certain issues; I think the internet definitely magnifies this phenomenon. Another consequence is that memory of certain events gets ever shorter as the news cycle spins faster and faster. The Singularity is near!!!.

Update: Guido Fawkes has a delicious twist on this whole business about “workfare” – it involves the Guardian.

“Nothing more poignantly reflects the collapse of the great global warming scare than the decision of the Chicago Carbon Exchange, the largest in the world, to stop trading in “carbon” – buying and selling the right of businesses to continue emitting CO2. A few years back, when the climate scare was still at its height, and it seemed the world might agree the Copenhagen Treaty and the US Congress might pass a “cap and trade” bill, it was claimed that the Chicago Exchange would be at the centre of a global market worth $10 trillion a year, and that “carbon” would be among the most valuable commodities on earth, worth more per ton than most metals. Today, after the collapse of Copenhagen and the cap and trade bill, the carbon price, at five cents a ton, is as low as it can get without being worthless.”

– Christopher Booker

Last night I went to the cinema, which I rarely do nowadays, and judging by the size of the audience for the movie that I and my friend saw, not many other people go to the cinema these days either. The place, in the heart of the London West End, was damn near deserted, apart from us and about three other people. Actually, though, the problem was probably the movie we were seeing, as I will now explain.

The movie we saw was Margin Call. Here is a short Rolling Stone review of it, which strikes me as pretty much on the money.

Okay: SPOILER ALERT. Stop reading this very soon if you don’t want the broad outlines of the plot handed to you on a plate.

When I started watching it, I knew nothing about Margin Call other than that a friend of the friend I was with had said it was the best current financial crisis movie he knew of. This makes sense. Margin Call is very much a trader’s eye view of the moment when the first of the waste matter started to move seriously towards the fan, around 2008. And, remarkable to relate, it actually shows “capitalism” (the quotes being because we all here know how government-intervened-in all these sorts of market have been) in a by no means wholly bad light. I am not a bit surprised now to have learned, the morning after, that this movie was written and directed by an ex-trader, a certain J. C. Chandor.

Plot approaching. Final warning. → Continue reading: What capitalism does when the music stops

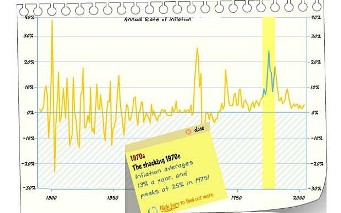

I was struck by this graphic, produced by the money printers at the Bank of England and reproduced in the Telegraph:

We are told (not least by the Bank of England) that deflation is the greatest threat to our well-being. But look at the Nineteenth Century. There’s no end of deflation there. And yet in this time they managed to build almost all of Britain’s railways (including three routes from London to Manchester), the Great Eastern, Crystal Palace, most of London, bring clean water and sewerage to the cities, introduce street lighting, make huge advances in science and medicine. and establish just about all the industries (coal, shipbuilding, steel etc) whose loss is so lamented, especially by people on the left.

OK, so I suspect a lot of those industries would have closed anyway but I fail to see how anyone could look at this graph and honestly claim that deflation was something to fear.

PS I now notice that the BoE does indeed talk about “Years of Deflation” between 1921 and 1931 and my understanding is that it was a pretty grim time. I would be interested to know if there’s a response to the implied claim that deflation is or was a bad thing.

‘“Quantitative Easing is a transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich,” he says, “It floods banks with money, which they use to pay themselves bonuses. The banks have money, and assets, so they can borrow easily. The poor guy, who is unemployed and can’t borrow, is not going to benefit from it.” The QE process pushes asset prices up, he says, which is great for those who own stocks, shares and expensive houses. “But the state is subsidising the rich. It is the top 1 per cent who benefit from Quantitative Easing, not the 99 per cent.”’

– Nassim Taleb, quoted on the Spectator’s Coffee House blog.

Jay Maynard posted a link to an advert from Moveon.org that illustrates how our children will have to pay off the government’s debt.

The trouble with this argument is that it concentrates on the movement of money instead of the movement of resources. This way of thinking can lead to all sorts of mistakes. If the government borrows a trillion dollars, the argument goes, that is a trillion dollars of taxes our children will have to pay in the future. We are borrowing from the future. Except that we are not, because only Doctor Who can transfer resources from the future, and he is busy with other things.

When the government borrows money it increases its bidding power for resources in the present. Resources move from private control to government control. It is the other bidders for resources who are really paying the price.

The children will not pay back the money because the government will never raise enough taxes to pay it off. Individual bonds mature, but they are replaced with yet more bonds. This will continue as long as there are enough people willing to join the bottom of the pyramid.

“And as to neoliberalism laid bare. Yes, the industrial revolution is the only way we humans have found of improving the living standards of the average guy in the street. I, as a liberal (even if neo) would like the living standards of the average guy to increase. Thus I support the industrial revolution. Yes, in all its mess and clamour: for it is making things better. I’m out and I’m proud. As a neoliberal I buy things made by poor people in poor countries. For that’s how poor people and poor countries get rich.”

– Tim Worstall.

I think I can formulate a new “Johnathan Pearce law”. Namely, the presence of the word “neoliberal” in a piece mocking markets and capitalism is almost always evidence that the author of said piece either does not understand what he or she is attacking, or is misrepresenting it, and also regards such ideas as being promoted by some sinister, all-powerful cabal, as suggested by that rather creepy use of the term “neo” in front of something else, such as “liberal”.

I have lost count of the number of opinion pieces written by finance commentators and journalists who complain that the austerity programmes of Europe are doomed to fail, because they cause perpetual economic contraction, resulting in shrinking government revenues, curtailing the ability to pay down debt – which was why the austerity programmes were embarked upon in the first place. And this will go hand-in-hand with a widespread, precipitous and neverending decline in living standards, which raises the spectre of social and/or political collapse. The alternative solution they generally propose comes from our good friend Baron Keynes. Naturally.

This is utterly wrong-headed. Naturally. I do not take much issue with the consequences of European austerity that have been identified, however austerity is not the cause of these. Austerity works just fine if governments do not implement it alongside tax increases. Which is what pretty much every austerity programme (either real or imagined) in Europe is either proposing or enacting. It’s the tax increases that will cause the vicious cycle mentioned above – not the austerity, stupid. Austerity alone redirects capital from government programmes to more productive areas of the economy, resulting in growth. But austerity plus tax hikes decreases the size of one part of the economy (the public sector, and this on its own is of course a good thing), whilst putting a yoke on the private sector by preventing individuals and companies from stepping into the breach, with punitive taxes discouraging investment or making it unaffordable. Of course this is a recipe for limitless economic contraction and social misery.

Citizens of a nation that requires a genuine period of austerity must be aware that there will be pain as structural adjustments take place whilst private sector investment slowly and surely crowds out a throttled and atrophying civil service. But pain is and was always going to be inevitable when the almighty spending binge so many governments have embarked upon over the last couple of decades unavoidably draws to a close, either through substantial policy shifts or sovereign default. The former is much less painful than the latter, but more politically difficult, so it seems. And, in dealing with the current debt crisis, Keynesians have never seen a can they haven’t wanted to kick down the road.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|