We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

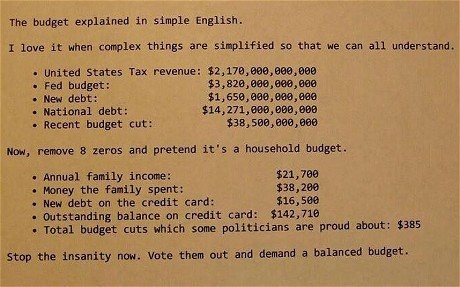

Not being wise in the ways of Twitter, I am not sure where Mr Eugenides got this piece of simple but effective graphics, only that he either acquired it or created it, one way or another, and that I found out about it because it was one of David Thompson’s clutch of ephemera last Friday:

I recall reading in one of Professor Parkinson’s books, I think in his classic Parkinson’s Law, that people only find it easy to have strong opinions about sums of money, or circumstances generally, that are within their particular and usually rather limited range of experience. So it is that a local planning committee will spend an hour arguing about a cheap loft extension, while nodding through an entire hundred million quid power station without discussion. Something along those lines. True, I suspect. Certainly true of many people.

So, the thing to do, with these otherwise unimaginably huge sums of money that politicians are slinging around nowadays, to keep all their various financial plates on sticks spinning fast enough, is what is done here, in the above graphic. Divide them all by the same (very large) number, until the original numbers become regular numbers of the sort regular people can relate to, while the numbers all nevertheless retain their relative sizes, to each other. The essential nature of what is going on is thus laid bare, for people who might otherwise be blinded by all the zeros, and all those bewildering words ending in “-illion”.

I agree with Mr Eugenides. This is clever.

And no, he didn’t invent it. It’s been around for a while.

I found Michael Barone’s piece here (thank you Instapundit) about ideological self-sorting very thought provoking.

Barone mentions a book called The Big Sort, which says that such self-sorting within the USA is bad, because it is “tearing us apart”. The book, says Barone:

… describes how Americans since the 1970s have increasingly sorted themselves out, moving to places where almost everybody shares their cultural orientation and political preference – and the others keep quiet about theirs.

Thus professionals with a choice of where to make their livings head for the San Francisco Bay Area if they’re liberal and for the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex (they really do call it that) if they’re conservative. Over the years the Bay Area becomes more liberal and the Metroplex more conservative.

Barone only concerns himself with how such self-sorting might be affecting the upcoming Presidential election, speculating that it causes liberals to live in an ideological cocoon and be bad at dealing with criticisms of their opinions. He instances the claim that Obamacare is unconstitutional, which liberals only took seriously when the Supreme Court suddenly did. Liberals had had months to prepare counter-arguments to that argument, or to rejig Obamacare so that it didn’t clash with the Constitution, but they saw no need to do either.

But there is plenty more to be said about ideological self-sorting. Might ideological self-sorting in due course become a major global tendency, with people choosing not just localities within countries, but actual countries, on ideological grounds? Is that already happening to any significant degree? If not, how likely is it that it might? And if it did start or has started, what might be its consequences?

The self-sorting Barone refers to is happening because moving within the USA is now quite easy. But time was when moving anywhere else was far harder, yet some people still did it, to particularly enticing destinations, from particularly abominable starting points. That people tried to hard to get out of the old USSR was one of the most damning and least answerable criticisms made against that horrible place.

The USA itself, all of it, is an exercise in ideological self-sorting, in the sense that most Americans are descended from people who bet the farm, metaphorically and often literally, on life in America being a better bet, even if they started out in America only with what they could carry. Americans are mostly descended from people who took a huge chance to make hugely better things happen for them. The great American exception to this is Americans descended from slaves, or from American natives. African slaves shipped to America placed no bets. They were chips in bets placed by others. Does that fact illuminate the seemingly still rather fraught relationship between black America and the rest of America? I think: yes.

But I am digressing into American history. What of the future of the world?

As a libertarian, I like the idea of ideological self-sorting, partly because it seems to me that there is a huge imbalance, in favour of minimal statism and against maximal statism, when it comes to how well each works out when practised only locally. Remember all those mental agonies suffered by Soviet communists when they started to realise that they were going to have to make do with “socialism in one country”, rather than everywhere? And remember how easy it then became to see which was better, Communism or not-Communism? Most of the world’s collectivists, although there are surely exceptions to this generalisation, are now collectivisms whose entire purpose is to deny “free riders” their free ride, anywhere on earth, thereby denying not only choice but exit. For collectivists, a world in which anti-collectivism flourishes, albeit only in some places, is anathema. They have to have it all, or their ideas won’t work, even in the limited sense of being inevitable and inescapable, and alternatives being hard to imagine because all suppressed. For most collectivists, it’s world government or nothing. But for libertarians, we only have to get a libertarian nation of some sort going, and to protect it from being completely shut down, and we’re in business.

We libertarians also have a big advantage in believing in being self-armed. Any libertarian national enclaves that emerge from the process of self-sorting that I envisage will, I believe, punch above their numerical weight, militarily speaking.

It is tempting to suppose that once ideological self-sorting gets seriously under way, if it does, it will then self-reinforce. As more people of one mind concentrate in particular places, those of other minds will have ever more reason to go elsewhere. This is the process that the author of The Big Sort dislikes, but which I favour for the world as a whole.

And then, when we all get to see which places work well and which work badly, you would at least hope that lessons would be learned. Sometimes that happens, as when many Eastern Europeans fled from Communism to America and then provided the political fuel for what America’s Communists and their useful idiots still describe as anti-Communist “hysteria”, in other words opposition to Communism and the belief that Communists ought not to infest the American government.

However, a big problem with ideological self-selection is that sometimes, having helped to wreck their original home, ideologically stupid people then move to other more successful places, but bringing their own stupid ideological opinions with them. Think of all the Muslims who now run away from overwhelmingly Islamic countries because of Islam’s despotic habits of government, only to bring those despotic tendencies with them to their new homes.

I’ve never been to the USA, but I occasionally read reports (and I seem to recall comments at this blog along these lines) that something similar happens there quite a lot, and is happening now, as “Blue” Staters run away from Blue States, but then vote for more Blue State stupidity in their new and formerly Red State homes. I trust I have the colour coding the right way round there. Personally I think this coding is wrong. How did the damn pinko taxers-and-spenders manage to get themselves coloured blue, and to colour their more enlightened and less parasitical enemies red?

So, to sum up, and hence to enable me to bring this rather unwieldy posting to a close, I think that, although it might not work out as well as I hope, I’m in favour of ideological self-sorting, and especially when it comes to self-sorting between different countries. But I’m sure I’ve missed out a lot of important things that could be said further on this topic, and I look forward to any such things that our commentariat might want to add to this.

“All the available Keynesian levers for achieving economic growth have been pulled, yet the recovery is one of the weakest since World War II. The problem lies with the way the “stimulus” was carried out, the uncertainty of looming higher taxes, and the antibusiness rhetoric and regulatory strong-arming of this administration.”

– Harvey Golub, Wall Street Journal.

In all the discussion about the Greek exit from the Euro I see a lot about wealth and poverty; about whether more damage would be done to the economies of Greece, Europe and the world by “austerity” within the Euro versus a default and a return to the drachma.

These are the questions of cost and benefit that it is respectable for world leaders to discuss. Discussion gets heated, I hear – voices are raised and cheeks flushed with anger. But the thing that really sends the blood rushing to a Prime Minister or a Chancellor’s cheek is pride, not money. Pride matters. Pride, shame and “face” in the oriental sense set billions of Euros coursing this way and that in a way that mere economics could never manage. Greek pride finds German diktats hard to bear – but not so unbearable as facing the fact that Greece did not join the Euro but rather was let in by condescending officials who turned a blind eye to obvious lies, like a university turning a blind eye to plagiarism in order to keep up the diversity quota. The Germans were proud of their Deutschmark, prouder still of their own nobility in giving it up for the greater good (with a little frisson of shame at the sinful pleasures of that export boom), and this is the thanks they get?

Bitterest of all is the wounded pride of the Eurocrats. Their sure touch was meant to gently shape history as the potter’s touch shapes the clay. Only the clay slid off-balance on the wheel and it has begun the trajectory that will end when it hits the wall with an almighty SPLAT.

Shapers of history really hate almighty splats. Hurts their pride, you see.

I really hate shapers of history.

This article on Greeks seeking refuge from their woes by emigrating to Australia is a bit old now, although I would be very surprised if the desire to go has changed at all. Greeks are now, by one measure I saw, the seventh largest ethnic grouping Down Under.

Of course, countries such as Australia and Canada, for that matter, might not be as easy to emigrate to as in the past if the would-be emigrant does not have the sort of skills that are likely to appeal to any granters of visas. And without wishing to sound sour about it, I could argue that the sort of enterprising Greeks who would have been welcomed with open arms by such countries have left their ancestral homes long ago. Another problem is that the very people who are trying to get the hell out of Greece are likely to be the sort most likely to drive their country back towards some semblance of prosperity.

Update: EU officials are starting to admit they are planning for a Greek exit. The end of Greece’s eurozone membership is very close now, I think.

Today I had an idea for a website that might be worth monetising. Nothing I could give up my day job for, but something that might bring in a few tens of pounds pocket money from Google Adsense. It would be fun; it might help fund my gadget habit. But:

Despite what you may have read somewhere on the Internet, any income earned from Google Adsense is taxable income. It makes no difference whether you earn £5 or £10,000 – this money must be declared to the Inland Revenue as income derived from self employment. Moreover, you must declare yourself as self employed as soon as you start work (this could be when you begin that new website or insert Google Adsense into a personal blog).

Says Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs:

If you’re self-employed on a temporary or part-time basis you must register for business taxes with HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) as soon as you start work. You’ll have to complete a Self Assessment tax return and are responsible for paying your own tax and National Insurance contributions on the income you earn.

Even if you don’t think you’ll earn enough to need to pay tax, you still need to complete a tax return.

Right now I pay my tax on Pay As You Earn, meaning my employer employs a department of people to do all the form filling. I like it that way. I have a very strong aversion to filling in official forms. When forced to do so my heart rate increases, I start to sweat, I hyperventilate, my writing hand cramps up, I have a stong urge to shout and throw things and people around me get nervous. This is partly indignation at being made to do something I do not want to do, partly the unease of spending time doing something that is not pleasant and not what I am skilled at (if I was good at organising paperwork and form filling I would have made different career choices), and partly irrational. And I can never find the damned supporting documents no matter how organised I have tried to be. I could elaborate yet further but thinking about it now is starting to induce symptoms so I must end this paragraph soon. The point is: the rewards would have to be very high to overcome this aversion, or I would have to make enough to pay someone else to do it for me.

A quick google suggests I am not the only one. Even for normal people, the cost, time and effort to fill in a tax return must be high enough to rule out all but the most serious of business ventures.

What is the cost to society of all the little side projects, hobbies and micro-businesses that do not get started because it is not worth the bureaucratic hassle?

Update: I found some tax examples graciously provided by HRMC. I particularly enjoyed the phrase “air of commerciality”. No grey areas here, then.

Samizdata’s favourite Member of Parliament, Steve Baker, has been elected an Executive Member of the 1922 Committee. What this shows is that he is the kind of Member of Parliament whom other Members of Parliament rate highly, and pay respectful attention to. It means that Baker has a Parliamentary following. He is not a loan (!!!) lone voice in the wilderness. Good.

In other words, ideas like this (written by Baker in response to some recent remarks by William Hague to the effect that we should all work harder) are now getting around:

Senior politicians must realise that hard work cannot produce prosperity without the right institutions. In addition to Adam Smith’s “peace, easy taxes and a tolerable administration of justice”, hard work must be rewarded with honest money which holds its value, not money which the commercial banks and the Bank of England can produce at the touch of a button.

Money loaned into existence in ever greater quantities caused the present crisis. It has given us a society based on crushing burdens of work in exchange for rewards which quickly disintegrate. That is the problem which must be solved if hard work is to have proper meaning and if we are to have a moral and just society which delivers prosperity for all.

Imagine a world in which the most powerful people in it started seriously to understand and to act upon notions like that. Thanks to people like Steve Baker we may eventually find our way towards such a world, and maybe (although one should never assume such a thing) quite soon.

I have admired Steve Baker MP ever since I first heard about him from my friend Tim Evans, and have liked him ever since I met him, at a Cobden Centre dinner a while back.

If you also admire Baker and what he is trying to accomplish, then please take the small amount of time needed to add a comment here saying so, even if you are not normally inclined to comment, here or anywhere else. Baker has several times told me, and I have no reason to doubt him, that encouragement of this sort makes a definite difference to his happiness, and to his willingness and ability to keep on keeping on.

I read this…

Leaders of the three biggest [Greek] parties met at the presidential mansion for a final attempt to bridge their differences, but the talks quickly hit an impasse as they traded accusations on a deeply unpopular bailout package tied to harsh spending cuts

…and…

Polls since the election show the balance of power tipping even further towards opponents of the bailout, who were divided among several small parties but now appear to be rallying behind Tsipras, a 37-year-old ex-Communist student leader

…and was then reminded of this by H.L Menchen which I have often quoted…

Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard

Greece is often credited as being the place where formal democracy was first practised in antiquity and so it seems fitting that it is Greece where the current social democratic order of regulatory statism enters its terminal state of Maenad frenzy, perhaps proving beyond all doubt that social democracy is unreformable via democratic means.

But do not kid yourself that the tragicomic indigent collective derangement on ever more florid display is something peculiar to the Hellenic world.

There has been a bit of a buzz in the internet and elsewhere about a new development off the US West Coast, known as Blueseed:

“More than 100 international tech companies have registered their interest in floating geek city Blueseed, to be launched next year in international waters outside of Silicon Valley. The visa-free, start-up-friendly concept launched late last year aims to create a fully commercial technology incubator where global entrepreneurs can live and work in close proximity to the Valley, accessing VC funding and talent as required. The bulk of registered demand germinated from the U.S. at 20.3%, Indian 10.5%, and Australians at 6%. Reasons: living and working in an “awesome” start-up- and technology-oriented space, proximity to Silicon Valley’s investors, and an alternative to having to get U.S. work visas for company founders or employees were key reasons. Cost:$1,200 to $3,000 per person per month.”

One of the bitter ironies of recent years has been how the US, a country that operates a worldwide system of taxes, as well as tightening its visa and other regulations, has made it not just harder for people, including the likes of software engineers, to enter the country, but also far less easy for expat Americans on short- or long-term trips abroad to do so and gain access to even basic financial services. (To view more on the latter point, see this entry of mine about the FATCA Act.) But as the Blueseed venture demonstrates, entrepreneurs and other liberty-loving people will try and find a way around the tentacles of Big Government. No doubt the Eyeores will say this is all futile, that the authorities will shut this sort of thing down, yadda-yadda, but the very fact that such ventures are being worked on at all is itself a kind of victory for certain ideas.

Reason magazine has a nice roundup on the Blueseed venture. And Patri Friedman’s Seasteading Institute is still going strong. Here is a great book on the subject, How To Start Your Own Country, covering the failed attempts and the mini-victories along the way.

I am presently in the Kingdom of Jordan. It’s a pleasant place. Developing quite rapidly. Friendly, welcoming people, although with a slight excessive tendency to charge foreigners more than they might charge locals for the same thing. That’s a sign of the stage of development the country presently occupies, however. Those higher prices are still cheap, by the standards most westerners are used to, and it is easy to get away with. Such are the joys of using an alphabet that westerners generally cannot read, too. (This sort of thing happens much more in Thailand than it does in Vietnam, for instance, as the Latin alphabet used by the Vietnamese makes it much harder to get away with. Despite the preponderance of alphabets used in India, it happens far less there, given that every establishment has an English language price list that is used by Indians far more than by westerners).

Amman is a city with quite a lot in common with somewhere like Bangkok, actually, although Bangkok is clearly more developed right now. A huge number of people have arrived in Amman from the countryside in recent decades, boosted by greater economic opportunities in the city than the desert as well as for political regions. Huge, relatively poor neighbourhoods have sprung up in East and South Amman. Crowded, sure. Desperate, not at all. In these neighbourhoods you find clusters of souks and markets and stores devoted to most imaginable products.

The new and rapidly growing middle classes are in West Amman. This is a mixture of highway flyovers, international restaurant and hotel chains (including many American restaurant chains not seen in Europe), shopping malls, and bad driving. It resembles Dubai in some ways, but is much less manic, much less the product of ruthless absolute monarchy and a viscous caste system (the Jordinian royal family being much more moderate) and contains many more pedestrians, even if the road infrastructure does not appear to have been invented with pedestrians in mind. There are various signs that money has entered Amman both from and via the UAE in various ways, but it doesn’t appear to be dominating the place. Plus, the weather is a good deal nicer, which helps a lot.

Go into the nicer shopping malls, and you find many of the expected international tenants that are generally to be found in middle class districts of rapidly developing cities with aspirational middle classes: Starbucks, Zara, etc. Anchoring each mall is a huge supermarket, selling vast amounts of food and non-food items at good prices – devoting roughly 50% of floor space to food and 50% to everything else, an outlet of the French chain Carrefour.

As I usually do in foreign countries like this, I devoted some time to wandering around the aisles of this supermarket. There is no section devoted to alcoholic drinks, this being an Arab country. Jordan is not an especially difficult place to find a beer. There are (fairly expensive due to high taxation) liquor stores throughout the country, mostly operated by members of the sizeable Christian minority, but drinking alcohol is something you separate from good wholesome activities like doing the regular shopping or having dinner in a public place, so there is no alcohol section and most restaurants do not serve alcoholic drinks. More entertaining is the section that would be devoted to things like ham, bacon, and salami in a European country. It is really amazing what you can do with turkey meat if you try, as anyone who has ever been served a halal English breakfast can vouch. And along with the Turkey salami there is the lamb salami beloved of Indian pizza aficionados. The regular meat section is full of lamb and beef, some of it imported from places like Brazil and Australia, and some of it sourced locally. The seafood section contains lots of fish that are described as coming from Dubai. An almost landlocked country is not going to be able to source most of its seafood locally (and, in the modern globalised world, who does, anyway?). The food section in general contains much catering to local tastes, and contains a very impressive mixture of local and imported.

Go into the non-food section and you find cheap TVs, computers, and other electrical appliances of all kinds. Cheap, but not too unsightly clothing in a mixture of western and local styles, kitchen utensils, tools and light kitchen, household and garden stuff. Toys. People familiar with the non-food section of a Carrefour or a Tesco anywhere else will be familiar with the contents here. A larger portion of this is imported, and needs to be less localised than the food, but where local sourcing and catering to local needs and taste is necessary, it is done.

Get a bus or taxi to the poorer neighbourhoods of Amman, and there are more downmarket malls in existence or under construction. These also have Carrefour outlets in them, possibly smaller ones. While Starbucks and Zara don’t necessarily travel all that far down from the upwardly mobile middle classes, supermarkets can. Everyone wants to buy good and inexpensive food, and cheap TVs and mobile phones appeal to all social classes as well. Carrefour have moved into the market by first providing cheap goods to relatively upmarket purchasing power by opening in malls that want them as tenants and with which signing contracts and negotiating bureaucracy is relatively easy, in so doing setting up supply chains and logistical systems in the country, and are now just starting to move out into the mass market.

Carrefour are, i think, the best in the world at general retail in middle income and developing countries. Their two most important competitors in this are Wal-Mart of the US and Tesco of the UK. Carrefour resembles Tesco more than it does Wal-Mart. Both Carrefour and Tesco began as food retailers, and as supply chain management became more and more important became better and better at it. Both were very good at negotiating the vagaries of their local planning laws and local labour laws, and expanded domestically to a huge extent as a consequence of this. Both added more and more non-food items as they opened larger and larger stores, to the extent that they became general retailers rather than simply food retailers. (The French use the word hypermarché or possibly the pseudo-Anglicism hypermarket to describe a large store that sells both food and non-food under the same roof. The English stick with supermarket regardless of how big it gets. As well as opening larger stores, they also opened smaller stores, becoming masters of everything from small convenience stores to giant mega markets (some of which do not even sell food). Using economies of scale to run both very small convenience stores and very large megamarkets at the same time was a relatively new thing, and both companies got this relatively early. Both took advantage of the new markets that opened up in Eastern Europe after 1989.

Wal-Mart on the other hand came from general non-food retail and added food later. → Continue reading: Urban development in Jordan and the power of French hypermarkets (but not French politicians)

The main problem with monetary policy is that there is such a thing as monetary policy.

– Detlev Schlichter

An article in the Telegraph by Colin Hines: Seeing off the extreme Right with progressive protectionism

It begins,

Tim Worstall’s piece accusing Compass and me of promoting “fascist economic policy” is a libellous smokescreen, hiding the fact that it is the very free market economic policies that he promotes that are bringing about the economic stresses and rising insecurity that allow and will continue to encourage the rise of the extreme Right.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|