We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

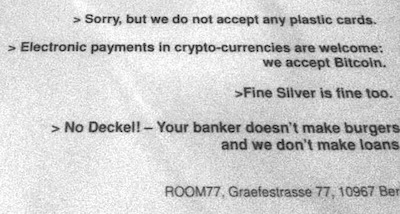

I would recommend clicking on the picture for the large version, in order to read the house policy of the establishment for the use of firearms on the premises.

My apologies for the poor quality of the picture. The light was dim, and I merely had a phone camera. I could have stolen the menu in order to get a better picture, I suppose, but I would not dream of violating the property rights of people of such obvious soundness.

Keynesian policies will keep us in a constant loop of distorted markets and growing imbalances. They guarantee us a Groundhog Day of economic depression.

— Detlev Schlichter, 8th November 2012

…triple-dip recession…

— The Bank of England, 14th November 2012

“Nobody pretends that hiking these taxes means “ordinary people” will have less tax to pay. But most folk still believe that companies can be made to pay taxes, shifting the burden away from the rest of us. I have news for you: they can’t. Corporations are artificial legal constructs: only people can ever pay taxes. The burden of taxes supposedly levied on companies is borne either by investors (through reduced returns on their capital), workers (via lower wages) or consumers (as a result of higher prices). Targeting firms is just a way of stealthily taxing these people, ensuring nobody really understands who is picking up the bill. It is because we’ve forgotten about these basic principles that we’ve ended up with a dysfunctional and incomprehensible tax system, as exemplified by the row over the practices of Starbucks, Amazon, Google and others.”

Allister Heath. (Non-UK residents who don’t subscribe may not be able to see the full Telegraph article, but it seems that quite a lot can, so I am putting this up with a disclaimer.)

A year ago today I posted Discussion Point XXXVI

What will happen to the Euro? I am not asking “what should happen”, but what will happen. Take this opportunity to put your predictions on the internet, and later be hailed as a true prophet or derided as a false one.

Come, take your bows, or your lumps, and predict anew. The fat lady has not yet sung.

Assuming that global warming really is happening, and really is caused by man, the rich will get off nearly scot free, as usual.

Ain’t that great!

The reason that it truly is good news for all humanity is that, whereas we have scarcely an inkling as to how to stop global warming, and our efforts to change human behaviour so as to mitigate it show an unbroken record of failure in all aspects save that of making new pretexts for tyranny, we do now know how to end poverty.

Hell, we’ve done it, in the rich world. Clue’s in the name.

If you are poor in the rich world, and are annoyed at me for saying this, do feel free to write in and complain. Email in, I mean, on your personal computer using your broadband connection or the one provided for free in a public library.

Hell, we’ve got halfway to doing it in great swathes of what was once the poor world. Last month I read about some Parisian hotel developer who caused outrage when he said his exclusive new hotel wouldn’t be open to Chinese tourists. Then he backtracked in a hurry and said “he was referring to ‘mass tourism’ when he used the phrase ‘Chinese tourists’.” Yes, I know hundreds of millions of Chinese are still poor, but think of how far we have come when a snob thinks of the Chinese when he denigrates ‘mass tourism’. Think of how far we have come when the outrage is expressed by Chinese internet users.

Hell, but hell on earth is getting less hellish by the day. There is harder evidence for this than my little anecdote above. Look up worldwide life expectancy statistics. This despite the mad folly of the economic policy of practically every government in the world. We have got so stonkingly, gobsmackingly, tingle-down-your-leggingly good at poverty reduction over the last few decades that we can even do it with socialism round our necks. Just think what we could achieve without that millstone.

We could exterminate the poor as a class. Would that not be agreeable? Quote me on that, you global warming activists who divide your time between Copenhagen and New York; I find the poor tiresome and would rather not have them around any more. I’d rather have all the Chinese, and all the Indians, and all the Africans getting rich and flying to London to take pictures of each other in front of London landmarks, in rotation if need be. It might cause a bit of global warming. Never mind, we rich folk can live with that.

Here:

The gold you see in the photo above was not found in a river or a mine. It was produced by a bacteria that, according to researchers at Michigan State University, can survive in extreme toxic environments and create 24-karat gold nuggets. Pure gold.

Maybe this critter can save us all from the global economic crisis?

On the contrary, this is not the dream, it is the nightmare. This bug, if it really can “create” 24-karat gold nuggets, or can in the future be persuaded to, might destroy gold as a meaningful replacement for the deranged fiat currencies now ruining all out lives.

A commenter tries to reassure us about the cost of this process, but his misspelling of “affect” does not inspire me with much confidence:

This is cost-prohibitive on a large scale, so it would/could not really effect the gold market.

Well maybe for a while, but technology these days is notoriously prone to plunge in cost with the passing of time.

The good news is that this bug doesn’t, like a government creating fiat money, create gold out of thin air. It creates it out of gold chloride. I presume that gold chloride is very roughly as rare as gold itself, as in similar order of magnitude rare. Heaven help the global economy if it is not rare. According to this Gizmodo piece, gold chloride costs “Less than gold, but still plenty”. Please, make it so.

As to the future, please, let no very large stashes of gold or gold chloride be found on nearby planets or asteroids.

Thank you Instapundit. Or not as the case may be.

Incoming from Jamie Whyte:

I have made a programme for Analysis on BBC Radio 4 which will be broadcast on Monday at 8.30pm. It concerns the Conservatives’ wrong headed abandonment of free markets following the financial crisis. You won’t learn anything you don’t already know — but then you are not the target audience! Nevertheless, you may be amazed to hear these things said on the BBC.

Relevant bit of the Radio Times (Monday October 8th):

Internet info from the BBC:

The financial crisis has made many on the political right question their faith in free market capitalism. Jamie Whyte is unaffected by such doubts. The financial crisis, he argues, was caused by too much state interference and an unhealthy collusion between government and corporate power.

Indeed.

I’m now watching a video of Hans Sennholz, produced by the Foundation for Economic Education.

Sennholz is talking about the Great Depression, arguing that freedom didn’t fail, politics failed, and that “if we repeat these government polices there is going to be another Great Depression”. I’m typing while he talks, but that is the gist of it.

Until now, Sennholz was just a name to me. Now he is a name, a face, a voice, an attitude. And a prophet.

This video was made (or should I say this film was shot?) on February 29th (!) 1988. I was steered towards it by Richard Carey (whom I SQotDed earlier this week) of Libertarian Home, to whom thanks.

The First World War use to be called The Great War. Soon, The Great Depression is likely also to become known by a different title, which also includes the word “First”.

What we are dealing with is a documentary formula, into which Hayek’s life and work has been stuffed. The particular formula is the one they use for pioneering scientists who discover bacteria or something like that, and the need is to stress just how isolated and way-out the fellow was considered by everybody else. That might be fine for doing the mathematician who cracked Fermat’s Last Theorem, and may lend itself to atmospheric long-shots of the presenter walking through empty courtyards and along echoing corridors, but Friedrich Hayek was not a man working alone, and his ideas built on the ideas of other earlier and contemporary economists. I kept waiting for the name Ludwig von Mises to crop up, and it never did. It’s kind of hard to discuss Hayek’s early years in Vienna without once mentioning Mises. The final straw came when the presenter described his work at the Institute of Business Cycle Research which was founded with Mises at the Chamber of Commerce where Mises worked, and where he held his legendary seminars, which Hayek attended, and even then she could not bear to utter Mises’ name. The following is far from a perfect analogy, but it’s like watching a documentary about Mark Antony with no mention of Caesar.

– Richard Carey is unimpressed by part two of the BBC series ‘Masters of Money’, featuring the work of F. A. Hayek. Part one was about Keynes. Part three will be about Marx. I know. What the hell kind of “master of money” was Karl Marx? Carey’s sentiments exactly.

I considered recycling Carey’s entire posting, which is not a whole lot longer than the above excerpt, to include in particular what he says about Marx, and also about the BBC. But it is no part of my intention to have anyone here ignoring Libertarian Home, where this posting appears. Do please go there, and read the whole thing. Or just go there anyway.

“It is easier to search for your own solutions to your own problems than to those of others. Most of the recent success stories are countries that not get a lot of foreign aid and did not spend a lot of time in IMF programs, two of the indicators of the recent indicator of the White Man’s burden…Most of the recent disasters are just the opposite – tons of foreign aid and much time spent in IMF constraints. This of course involves some reverse causality….the disasters were getting IMF assistance and foreign aid because they were disasters, while the IMF and the donors bypassed success stories because those countries didn’t need the help. This does not prove that foreign assistance causes disaster, but it does show that outlandish success is very much possible without Western tutelage, while repeated treatments don’t seem to stem the tide of disaster in the failures. Most of the recent success in the world economy is happening in Eastern and southern Asia, not as a result of some global plan to end poverty but for homegrown reasons.”

The White Man’s Burden, pages 345-346, by William Easterly (2006).

Easterly is a US-based economics professor and has been a senior economist at the World Bank, as well as a columnist and regular commentator. His book, which despite the title is anything but a piece of Western triumphalism, is an example of a man who is prepared to discard ideas, however seemingly noble, if the results don’t stack up. And it is a book that ought to be compulsory reading for Britain’s coalition government as it continues to pour billions into overseas aid, despite the questionable results and even more questionable assumptions behind it.

For far too long, the late writer and economist, Peter Bauer, was, like John the Baptist, a “voice crying in the wilderness” when it came to government aid programmes. Let’s hope more people wake up to the nonsense that a lot of so-called “aid” actually is.

Together with other central banks, the ECB is flooding the market, posing the question not only about how the ECB will get its money back, but also how the excess liquidity created can be absorbed globally. It can’t be solved by pressing a button. If the global economy stabilises, the potential for inflation has grown enormously

– Jürgen Stark

Detlev Schlichter’s latest posting – Stimulus, to infinity and beyond – is up.

Beginning:

There was a beautiful symmetry to last week’s policy announcement by the Fed. Precisely a week after the ECB had pledged its commitment to unlimited purchases of Euro Zone government bonds, the Fed declared that its new round of debt monetization – ‘quantitative easing’ or QE3 – would be open-ended.

Unlimited, open-ended. The concept of stimulus has certainly evolved since the crisis started.

End:

This will end badly.

Nothing to add to that myself. Other than: do what I am about to do, which is to read the whole thing.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|