We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

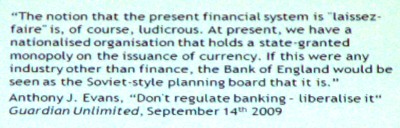

Snapped by me a fortnight ago, at the LA/LI Annual Conference at which Anthony Evans was the final speaker. I’ve straightened and sharpened it as best I could. A copyable, pastable and more readable version of the text from which this is taken may be read here. More photos of the speaker taken that same day can be viewed here.

UPDATE: Anthony Evans website, articles, blog.

Mark Wallace of the TaxPayers’ Alliance, writes, at Devil’s Kitchen, thus:

Part of the problem for eurosceptics has been that we have too often only engaged in one half of the argument. To be fair, we’ve all made a pretty good case that the EU is a costly, harmful, antidemocratic monstrosity – so much so that the public are in great majority convinced of that.

It is the second half of the argument which has been somewhat lacking – what is the positive alternative? Convincing people there is a problem with the current situation is not enough; we need to lay out what life would be like without the EU, how things could be better and, crucially, how it is perfectly feasible to get there.

To that end, the TaxPayers’ Alliance is publishing a new book, Ten Years On: Britain without the European Union which lays out a vision of what Britain could be like in 2020, governing ourselves and with the freedom to cooperate and trade with whomsoever we like.

Even better, it is available free to pre-order through this link!

I think this is spot on, not necessarily in the sense that Britain would be better off out of the EU, but in the sense that this is the bit of the argument that has been neglected. After all, the same lying politicians, stubborn bureaucrats, town hall little Hitlers and idiot voters that got us into this mess would still be around to screw up the alternative. So how would being out of the EU necessarily make their position weaker? Might the alternative actually be worse? I believe – partly because I want to believe (see paragraph one of the quote above) – that it would an improvement, but I would like to hear this argument made.

Also, would we, Norway style, still have to endure EUrocrats making our rules for us, for the privilege of trading with the EU? Seems unlikely, but again, I’d like to hear the argument.

So, as Instapundit would say, it’s in the post. The ordering seemed to work very smoothly. Nothing like free of charge to simplify things.

Bishop Hill:

Devil’s Kitchen has a must-read post up, detailing the increasing use of enabling legislation by the government. And he doesn’t swear at all – must be serious.

Indeed.

I daydream that one day, a British Cabinet Minister will grab hold of one of the laws that DK writes about, where it says that, if there is a crisis (and it is up to him to decide), then he, the British Cabinet Minister, may do whatever he considers to be appropriate (i.e. whatever he damn well pleases). I daydream that he, the British Cabinet Minister, will bring into the House of Commons a huge list itemising all the laws that he is now going to repeal, just like that, no ifs no buts no discussion, because he, the British Cabinet Minister referred to in one of the laws, says so, on account of there being a crisis caused by all the damn laws.

Impossible, you say? Very probably. But it is surprising how much of history consists of impossible dreams that were dreamed during earlier bits of history.

So asks John McWhorter:

The main loss when a language dies is not cultural but aesthetic. The click sounds in certain African languages are magnificent to hear. In many Amazonian languages, when you say something you have to specify, with a suffix, where you got the information. The Ket language of Siberia is so awesomely irregular as to seem a work of art.

But let’s remember that this aesthetic delight is mainly savored by the outside observer, often a professional savorer like myself. Professional linguists or anthropologists are part of a distinct human minority. Most people, in the West or anywhere else, find the fact that there are so many languages in the world no more interesting than I would find a list of all the makes of Toyota. So our case for preserving the world’s languages cannot be based on how fascinating their variegation appears to a few people in the world. The question is whether there is some urgent benefit to humanity from the fact that some people speak click languages, while others speak Ket or thousands of others, instead of everyone speaking in a universal tongue.

See also this article about Indians who write their novels in English rather than in one of the local Indian languages, partly because they just do, and partly in order to increase their potential readership around the world. The piece is by Chandrahas Choudhury, himself the author of a novel in English. He also blogs.

Both pieces were recently linked to by Arts & Letters Daily, to whom thanks.

I suppose a danger of everyone on earth speaking the same language, as was explained in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, is that we would all of us then understand each other’s insults.

… the … Babel fish, by effectively removing all barriers to communication between different races and cultures, has caused more and bloodier wars than anything else in the history of creation.

But this is to assume that hostility causes wars. I think it is at least as true to say that wars cause hostility.

Quite aside from the rights and wrongs of English conquering everyone and everything, there is the intriguing question of whether it in fact will so triumph, or whether any other potential universal language, like Spanish or Chinese, will triumph, in the nearish future. Perhaps English will triumph, but in the process it may itself fragment. If one language does triumph, it may well be English, but not necessarily English as I know it.

Yesterday I recorded a conversation with Paul Marks, a regular contributor here. My purpose was to enable all who are curious about who and what Paul Marks is to learn more. And the best way to learn more about Paul Marks is to listen to him talk not about himself (which we only did for about ten seconds) but about some of the things that he has been thinking about in recent years and in recent months.

In recent years, Paul has been brooding on the impending financial disaster which he saw coming. You know, the one that “nobody saw coming”. Well, he did. How come? More recently he has been pondering the Marxist background and foreground of US President Barack Obama. What, Barack Obama as bad as Ho Chi Minh? Yes, he replied. He didn’t just say it, he explained it and he justified it.

As I said at the end of the convsersation itself, and as I repeated in the posting I did about the conversation on my personal blog soon after it had been recorded, I think it went well. Since then, I have listened to it right through again, and I remain very content with it. If, on the basis of this plug, you feel inclined to have a listen yourself, this will occupy somewhat under half and hour of your time. Enjoy.

Patrick Crozier recently did a podcast interview with our own Michael Jennings, on the subject of businesses that are now failing, which I heartily recommend. Michael zeroed in, in particular, on bookshops, spectacles, newspapers and – very topically for today (although the conversation itself took place a short while ago) – postal services.

A particular point which Michael emphasised was how the same technology can start out by helping a particular business, but then turn round and smack it in the vital organs.

The dead tree press, for instance, thanks to the lead given by men like Rupert Murdoch, at first thrived on computer technology. Now look at it.

Computer technology also started out by making postal communication a better deal rather than a worse one. Junk mail, without the e- at the front, was, after all, an early bastard child of computers. And postal services the world over, like most businesses, have enthusiastically applied computer technology to their various activities, making old-school physical communication that much quicker and cheaper and thus more attractive to users than it would otherwise have been. But again, now look at the predicament of post offices, and in particular, today of all days, our own Royal Mail. Note how easily the Royal Mail itself is managing to communicate with us all, despite not being able to send out any letters.

I found particularly interesting what Michael said about the book-selling trade. Once again, the same pattern repeats itself. Early computer technology helps the old-school businesses, in this case the big book-selling chain stores like Borders, by making them more organised. But the big Borders expansion has now gone into reverse, with, for instance, the Oxford Street, London, manifestation of it having just now closed.

Book selling works well on the internet because books are a standard product that you don’t necessarily need to smell, fondle, weigh in your hand, and so on, like you might want to do with something like a camera or a laptop computer. But a product doesn’t have to be generic and standardised to work well as an internet purchase. It just has to be easy to describe with complete accuracy. Most pairs of spectacles are a bespoke product. You just have to know exactly what you want. But this is doable. So high street opticians are a good candidate for execution any year now. I am sure that the Samizdata commentariat will be able to suggest more candidates for imminent death.

Patrick and Michael ended their conversation by agreeing that they didn’t think that the bad economic conditions we’ve been having lately are going to go away any time soon, which means, as Michael pointed out, that people are not going to stop being highly price-conscious, which is one of the big drivers of computerisation and internet-isation, and failure for all the businesses that can’t adapt to these processes.

I’ll end this by recycling an interesting comment that Michael has just added to Patrick’s posting:

As Patrick said, we recorded this over Skype. I was in my home in South-East London talking into my laptop and Patrick was in his home in South-West London conversing with me and replying. This may be another example of what we were talking about. In the late 1990s the traditional former telco monopolies had a huge boom, due to their being seen as the companies that would provide this bold internet future. Now, where are they? BT is now a company that one barely notices, although they do admittedly own the copper that our conversation was going through between my flat and the exchange (although not the equipment in the exchange). Mobile carriers themselves are probably next in this regard.

Like I say, recommended.

There is swear-blogging, and then there is this:

Emily Thornberry MP: a very stupid and thoroughly unpleasant person who should be severely punched in the cunt, and then thrown into the sea.

That’s way too far over the top of the top for me. Maybe I’m getting old. It’s in a posting in response to a posting here by Johnathan Pearce on Saturday, about how giving women rights at work will make them more expensive to employ and consequently cause women to be employed less.

I’m genuinely in two minds about this swear-blogging thing. (See also this blog.) On the one hand, as with the passage quoted above, I think it can be horribly offensive by almost any standard and liable to make a lot of people think badly of something I value, namely the libertarian movement. (If you look under affiliations, you see that DK is affiliated to the Libertarian Party.) I can foresee a time when such passages as the above will be quoted in evidence against us all. If anyone points out that “they” (i.e. us libbos) were writing things like that, and none of “them” complained, well, I did. And if this posting alerts enemies of the libertarian movement otherwise unalerted and it all blows up in our faces, then the sooner the better, I say. Get the argument about swear-blogging over with.

On the other hand, this kind of language does at least communicate just how angry people get about the plundering and bossiness of politicians. If you are similarly angry, read on, Devil’s Kitchen is for you. You are not alone. It libertarianism was only written calmly and dispassionately, something important would be lost.

One thing I do know is that if Devil’s Kitchen was nothing but the above offensiveness, I wouldn’t give a … flip … about him. It is because he writes good stuff about important topics, in among the effing and blinding and sometimes worse, that I now ruminate upon the wisdom or lack of it of how he writes. Whatever I end up thinking about this, I am not now recommending and never will recommend that what I might consider to be excessively sweary swear-blogging should be illegal, to read or to write.

The story, which I learned about today, here, has already done the rounds. After all, it happened a whole two days ago. Still, all those interested in new media, and all who fret about where news will come from if newspapers collapse, will find (will have found) the story interesting. It’s the sort of thing they presumably now study in media studies courses. If not, they should. Not that you need to be doing a media studies course to be studying the media (and the rest of us certainly shouldn’t have to pay for you to do this), but you get my drift.

Basically, a London Underground staff member called Ian swore at an unswervingly polite old man who had got his arm stuck in a train door and was trying to explain that fact to Ian. Ian said (shouted more like) that the old man would have to explain himself to the police. At that point a nearby blogger who just happened to be there, Jonathan MacDonald, started up his video camera, and soon afterwards did a blog posting, complete with video footage, about what he had witnessed. In due course the mainstream media tuned in, and went ballistic.

If you do feel inclined to follow this up, I suggest reading the original blog posting, and then some thoughts, also by Jonathan MacDonald, concerning what it all means. He supplies copious further links.

About two decades ago, I gave a talk to an audience that included some devout environmentalists. In one of my answers to one of these persons, I said that if a technological fix could be found for, say, the hole in the ozone layer (a big topic in those days), by e.g. sending a rocket up into the hole and shovelling ozone out into the hole, thereby mending it, that would mean that we could be a little more relaxed about causing the hole to get big in the first place. In general, I argued, technologically fixable problems are less of a worry than technologically unfixable ones.

It was if I had said that, on account of a new kind of metal cleaner recently invented, it had become less of a problem if people broke into churches and pissed on crucifixes. It was, I was told in shocked tones, the very idea that problems could be solved with technology that was at the heart of the evil that humanity was facing.

So, I have long understood that environmentalism is a religion, and that the purpose of proclaiming the existence of environmental problems is absolutely not that they should be fixed, but they should be instruments to accomplish the transformation of people and how they live from what people actually are and how they actually live, to … something else. Technological fixes are evil. The worst evil of all.

Which means that Dominic Lawson is entirely right to say that plausible technological fixes for the allegedly huge environmental problems that we allegedly face now will cause rage rather than rejoicing among all the true believers of the Church of Mother Earth. Technological fixes will deprive that church’s devotees of their excuse to bully the rest of us into living different and less – in their eyes – sinful lives.

Even so, I enjoyed reading Lawson’s piece, with its sensationally unequal comparison between how much the current measures now being put in place by the world’s politicians to solve the alleged enviro-crisis, which are calculatedly and deliberately very hurtful to the world economy, compared to how absurdly cheap such technological fixes might be.

The significance of the ideas Dominic Lawson reports on (which are among those contained in this book) lies not in their ingenuity or in their political relevance in any immediately imaginable near-future. It is their irreverence – their sacrilegiousness – that is significant.

There is a superb blog posting up today by Mr Eugenides, about Trafigura, and about Trafigura’s attempts to stop people voicing opinions about Trafigura. Trafigura? I know. Who are and what is Trafigura? Never heard of Trafigura? Well, if you hadn’t heard of Trafigura before this week, you have heard of Trafigura now. And you’ve certainly heard of Trafigura now. Says Mr Eugenides, in his blog posting about Trafigura and about the libel lawyers that Trafigura has unleashed:

One day these highly-remunerated libel lawyers are going to wake up and realise that they aren’t being paid in guineas any more and that, thanks to this thing called the Interwebs, they can’t shut down freedom of speech the way they used to in the old days.

Indeed. The story is that Trafigura recently hired Britain’s swankiest libel lawyers to tell the Guardian not to mention in the Guardian that Trafigura had been unflatteringly asked about in the House of Commons, by a Member of Parliament. You read that right. The Guardian may not report on the proceedings of the House of Commons. Trafigura has been doing allegedly bad things in Africa, it seems, and an MP asked about Trafigura, in the most supposedly public place in the land, but Trafigura want their name, Trafigura, not to be reported in this connection. To which end Trafigura’s libel lawyers have told the Guardian, in a libel lawyer way that you apparently have to obey, that Trafigura may not be mentioned in the Guardian. No Trafigura, Guardian.

Here is the question, about Trafigura, recycled by Guido, in which the word Trafigura appears at the end, where its says: Trafigura. And thanks to Guido for linking to the Mr Eugenides piece about Trafigura. I would hate to have missed Mr Eugenides’s piece, about Trafigura. → Continue reading: Trafigura

I repeatedly read non-atheists saying that atheists are foolish in various ways. Strident, arrogant, irrational, even unscientific. I obviously read a better class of atheist because I seldom see this, but today I did come across a foolish piece in which atheist Paul Fidalgo tries to accuse Tony Blair of saying, in a recent speech at a Georgetown University get together of Muslim and Christian scholars, that atheists are terrorists.

I say “tries”, because Fidalgo himself admits that he was obliged to remove the word “equates” from his first version of the title, and replace it with “groups”. In other words to admit that he had failed in what he was trying to argue.

This article originally used the word “equates” in the headline, which I have changed to “groups.” Realizing that Blair never specifically makes a perfect equivalency between atheism and religious violence, I thought this was a fairer word to use.

But instead of admitting that his argument is holed below the water-line, Fidalgo leaves it there, accusing Blair of wanting to say or trying to imply, blah blah, what he never did say, and actually never even tried to say. → Continue reading: Siding with Tony Blair against his atheist critic

BBC Climate correspondent Paul Hudson asks What happened to global warming?:

This headline may come as a bit of a surprise, so too might that fact that the warmest year recorded globally was not in 2008 or 2007, but in 1998.

No surprise to me about those dates. But yes indeed, big surprise that a BBC person is saying this.

But it is true. For the last 11 years we have not observed any increase in global temperatures.

No matter how hard we tried.

And our climate models did not forecast it, even though man-made carbon dioxide, the gas thought to be responsible for warming our planet, has continued to rise.

So what on Earth is going on?

What indeed? This is not the usual BBC line, is it? Whatever your opinion of A(nthropogenic) G(lobal) W(arming) – mine has for quite a while been that it is wall-to-wall made-up nonsense – I think you will agree that this is quite a moment, as is further illuminated by the fact that Instapundit has just linked to the above piece. Which is how I just heard about it.

I wonder if the BBC feels inclined to switch to being AGW-skeptic in order to try to make difficulties for David Cameron – stirring up his own party’s AGW skeptics against him etc. David Cameron has swallowed the AGW argument whole, or at least pretended to. With that man, you never really know what he really believes. Apart from believing in David Cameron, David Cameron probably doesn’t know himself what he really believes, and probably never will.

But I digress. Mainly I just have a question. Is it right that this marks a big shift for the BBC, or have I not been paying attention properly? This is entirely possible. I don’t follow this debate religiously, and certainly do not know the names of all the key players on this topic in the mainstream media. Maybe Hudson has been a known unreliable for some time. But whatever the truth of that, I will certainly keep my eyes and ears open for what others, especially people like Bishop Hill, make of this, in the days and weeks ahead.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|