The following is an account of a visit to Chernobyl I made over the summer. However, first an only slightly related personal plea, if anyone in our wonderful techie readership has expertise in the electrical systems of Hitachi hard drives, or knows a business with specific expertise in data recovery from such drives, could you please read this and get back to me. I would stress that expertise is more important than location: if you are or know someone really good in Taipei or Fresno, that is still greatly helpful.

In 1986 I was in my final year of high school in Australia. The Cold War was still in force, and although some liberalisation had occurred in the Soviet Union, it felt like part of the natural order of things. The USSR was dark, strange, mysterious, and seemingly eternal. There was a wall down the middle of Europe, and nothing was more stark than the two sides of that wall. In April that year, workers at a nuclear power plant in Sweden detected excessively high levels of radiation. After briefly panicking about their own reactor, they realised that the radiation levels were higher outside than inside the building, and that the radiation was coming from somewhere else. Within a few days we knew that there had been an accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant north of Kiev in the Ukraine. Over the years, we have learned more about what happened, and the word “Chernobyl” has entered the world vocabulary, at times as a general word denoting a terrible catastrophe or destruction. We learned of firemen sacrificing their lives to contain the disaster, of evacuations of cities, and eventually of a strange forbidden zone that reflected the times and earned a place in certain kinds of popular culture. Even culture that preceded it sometimes now seems to have a strange sense of being about it.

I am not usually one for organised tours, but there are places where one has no other alternative. Sometimes one needs the expertise of a local, and sometimes there are places in which one is simply not permitted to go other than on an organised tour. The so called Zone of Alienation around the Chernobyl nuclear reactor is such a place.

In any event, in June I visited Kiev (*) in the Ukraine. I have been pushing further east into the former communist countries on my travels in recent times, and going to the Ukraine was an obvious next step. I have still not been to Russia – the amount of nonsense that one must go through to simply get a Russian visa rather puts me off – but the Ukraine is now in an interestingly semi-westernised state where one can get there on discount airlines and most westerners no longer require a visa, but which is outside the EU and NATO. Democracy and what middle class that exists is relatiely fragile, and one still can encounter Soviet style bureaucracy. Businesses from further west tread cautiously.

However, my main reason for going was that I wanted to see that mysterious forbidden zone. A number of tour organisations advertise tours of Chernobyl. They have a slightly odd way of quoting prices – basically, they quote the total cost for the tour party, rather than for individuals. The implication is that there are only a few tours, and they do not get enough people to fill them up every day. This seems a slightly strange way to encourage demand, as I was perfectly willing to pay the $180 per person for part of a group, but not the $600+ for a tour by myself. However, I sent an e-mail to one of the tour companies giving several days on which I could come, and asking whether it was possible to join an existing group on one of those days. I received an e-mail back straight away confirming a convenient date, and after paying some money (through a local Ukrainian online payment service that seemed rather more encrypted than I would encounter further west) and sending my passport number in order that the Ukrainian government could issue a permit for me to visit Chernobyl, everything was organised. At least, it was organised if I could reconcile the (Latin) address to meet with the (Cyrillic) street signs and maps. The evening before the tour, I walked to what I believed was the correct location, and found a travel agency, but no sign of the company I had sent money to or any indication that here was where tours of Chernobyl started. Clearly, Chernobyl tourism was not that well developed, and was run by people without offices in central Kiev.

However, no problem. When I returned in the morning I was greeted by someone named Sergei, and I discovered that there were about nine people going to Chernobyl that day. I paid the balance of the fee (in Ukrainian currency, quoted at a surprisingly fair exchange rate charged from the USD fee quoted) and introduced myself to the other passengers. One of them was Czech, another was Polish, and the remainder were Finns. I asked one of them if they were traveling together, but no: they had mostly signed up for the tour independently. I didn’t ask why Finns in particular were touring Chernobyl. The simple reason was that Helsinki simply was not that far, but I allowed my mind to imagine the Finns coming to see what their forefathers had fought so hard to avoid being forced to join.

Soon, we were on the road. Chernobyl is close to the border with Belarus, a little over 100km north of Kiev. When the power plant was first planned, there were proposals to build it only 25km from central Kiev – almost in the suburbs of the city. However, although the glorious system of socialism meant that accidents were not possible, the Soviet Academy of Sciences had none the less had second thoughts, and the location of the plant had been moved 100km away.

As we drove north, Sergei told us various things about the tour. (“This is Mikhail. He’s our driver. He doesn’t speak any English but he’s a nice guy”) Some history of the disaster, one or two pieces of which were clearly folklore rather than fact. (When the disaster had occurred, humans had been unable to detect the radiation, but animals had some primeval sense of such things and had fled). Instructions that we should be careful and not hurt ourselves on any broken glass or any other detritus in the forbidden zone, for if such things happened then they might not be able to conduct such tours again in the future. Warnings that we should not take any photographs of the fences or security detail around Chernobyl. Taking photographs of the site itself would be fine, but the security around it was forbidden. Bureaucrats and officials are the same everywhere.

After an hour or so, we were at the outer boundary of the exclusion zone around the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. This originally consisted of a circle 30km in radius around the site of the accident. It has been adjusted in places and is no longer an exact circle: contamination is very uneven and the boundary has been adjusted in various places to reflect this. The 30km zone crosses the border between Ukraine and Belarus, and there is a separate zone controlled by Belorussian authorities on the other side of the border. To enter the 30km zone, one must go through a checkpoint, and present one’s passport to the Ukrainian border guards who monitor the zone. The check was reasonably thorough: my name was checked off a list and I was compared with the picture on my passport. Whether there was some actual reason for this check or it is just some lingering post-Soviet bureaucratic, thing, I have no idea. I can understand a desire to keep people out who are not explicitly on a tour, but the point of establishing much more than that I am genuinely a foreign tourist rather escapes me.

I was not permitted to take photographs of the checkpoint, but it looked just the same as any other military checkpoint anywhere else. The last time I went through such a checkpoint was when I visited the world’s other most famous forbidden zone, the one between the Koreas. The buildings had the same built of corrugated iron quality. The fences looked the same. The soldiers looked the same. They wore different uniforms and had different ethnicity, but the “world weary military” quality overrode any such considerations.

And what is this place called? Well, the Ukrainian name is Зона Ð²Ñ–Ð´Ñ‡ÑƒÐ¶ÐµÐ½Ð½Ñ Ð§Ð¾Ñ€Ð½Ð¾Ð±Ð¸Ð»ÑŒÑької, which Google’s language tools translate as “Chernobyl Exclusion Zone”. The most common full name in English is the Zone of Alienation, although in conversation I never heard anyone refer to it as anything other than “The Zone”.

In any event, we were soon enough through the checkpoint. As we drove through the zone, we were told of the so called “samosely”, people who moved back into the zone after the evacuation of 1986. After the disaster the people who lived close to the reactor were quickly evacuated. They were not told the full details of what had happened, and in order that they would leave quickly and not spend too much time collecting their possessions, they were told that they would only have to leave their homes for a few days. This led to complications – a large group of people who really had nowhere to go. In the places they were taken, they were not especially welcome. Children were mocked and rejected for being “contaminated”, and adults received similar, perhaps less overt prejudice. This led to a substantial number of people – low tens of thousands in number – returning illegally to the Chernobyl zone. In the years since, and despite various attempts from the Ukrainian government to evict them some of these people have always stayed. In recent years the Ukrainian authorities have come to tolerate and regularise this situation. People living in the zone are provided with electricity, and a doctor is sent round to provide necessary medical care.

The number of such people has dwindled and is now relatively small – of the order of 400 people, the youngest of who are apparently in their late 40s. Approximately half of the samosely live in Chernobyl. As drove towards the town, a couple of gaps in the trees were pointed out, through which the frames of derelict buildings could be seen. Occasionally, it was pointed out that people lived there. “They don’t like visitors”.

I can imagine.

Soon, though, we were in Chernobyl town.

Chernobyl is an ancient town, dating from at least as early as the 12th century. A century ago it was a major centre of Hasidic Judaism and the vast bulk of its population was Jewish, and later it gained a substantial Polish population. The 20th century was particularly terrible for such people in this part of Europe. The Poles were deported to Kazakhstan during Stalin’s purges of the 1930s, and almost of of its Jews died in the Holocaust. In 1986 the town had a population of approximately fourteen thousand Ukrainians.

When the site was chosen for Ukraine’s first nuclear power plant in the 1960s, Chernobyl was the closest town, from which the power plant got its unofficial name. Officially it was the Vladimir I Lenin Nuclear Power Plant. However, the town was not close enough or large enough to house the workers for the power plant, and new, closer cities were created for this. Approximately 120,000 people in total lived in what is now the forbidden zone. The town is in the outer zone in an area of this zone, in an area of relatively low contamination, making it a convenient place for administrative personnel and watch staff to be stationed. People who work in the zone are not allowed to spend long continuous times inside it, but such a location is none the less convenient. In addition, approximately half of the people living illegally in the zone live in Chernobyl.

That said, Chernobyl looks nothing like an ordinary Ukrainian town. Tasks such as cutting grass and painting buildings are not tasks that it is worth going into the zone to do in any serious way, so the town is relatively dilapidated, run down, and overgrown, even the exteriors of buildings that are occupied. And a few hundred people now occupy a town that was once occupied by fourteen thousand, so the bulk of the town is the same green overgrown remains of buildings that one finds throughout the zone. Those administrative functions that take place in the zone exist in the sort of functional prefabricated buildings that long standing but supposedly temporary military operations work out of everywhere.

We were taken into one of the prefabricated buildings, sat down, and briefed. We were joined by someone who was described as “a former power plant worker”, whose name we may not have been told. He greeted Sergei warmly. He was wearing fatigues, and spoke no English. He may or may not have actually been a former power plant worker, but his bearing now was “soldier”. He was clearly our official minder on the trip. After being briefed, we were asked to sign a disclaimer, basically stating that we would not hold the Ukrainian government responsible for any accidents, subsequent illnesses, experiences in which we grew extra limbs or heads, or anything at all that might or might not have occurred as a consequence of our tour. Once again, the feeling and procedure was utterly identical to what had happened in that other zone in Korea. The disclaimers even seemed to be printed in the same 1960s font on the same low grade recycled paper. The one difference was that in Korea, we each signed a disclaimer on a different piece of paper that was given to us as a souvenir at the end of the tour. In Chernobyl, we all signed the back of the same piece of paper, that was retained. Clearly, the tourist aspects of forbidden zone tourism were not quite as well developed here. Give them time.

Once again like the Korean DMZ, Chernobyl is famed in certain circles as an instance of an “involuntary park”: a place where wildlife can thrive without human activity. We saw little animal life on the tour, although there was certainly evidence of its presence. There were a large number of cats in Chernobyl town, however. This was covered in the briefing. “Don’t touch them. They have rabies”. I didn’t touch them.

After the briefing, it was time to proceed. First stop was the memorial to the firemen who were the first men on the scene of the accident in the early hours of 26 April 1986. Nobody knew what had occurred, but the reactor building caught fire. As was their job, these men arrived on the scene and put the fire out. Over the next few days, they died. Brave men.

The plaque on the memorial translates approximately as “They saved the world”. An exaggeration, one thinks, although they undoubtedly did save many lives. As I said, brave men.

Before we reached the power station itself, we got a brief look at the “Chernobyl 2” array in the distance. Although the Chernobyl reactors were of a design that was optimised for the production of Plutonium-239 for nuclear weapons as well as for the production of electricity and as such probably did have Cold War relevance, the plant was not secret, closed, or inaccessible. On the contrary, it was a showcase, and was presented as a model “Atoms for peace” project, in which the superior Soviet system provided for its people. However, there was a genuine Cold War installation nearby, the huge Duga-3 over the horizon radar array that was responsible for the “Russian Woodpecker” signal that was well known to shortwave radio operators in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1986 this was a sensitive site and very secretive in operation. It contained an underground bunker designed to survive a nuclear attack and provide power and resources for survival for as much as ten years after. As such, it had all the general creepiness that we associate with the Cold War. When people were evacuated in 1986, nobody knew what had happened. It was believed by many for some time that the evacuation had something to do with this Cold War station of unknown function, and that saying it had to do with the power plant was perhaps a cover-up. This radar array has long been closed, but it still looks weird in the distance.

In the Chernobyl zone, some places look like they were abandoned before the dawn of time. And yet, at the same time, other places look like they were left at the end of a day’s work, and that the people who left them will return and continue the job tomorrow. If tools were taken out of a closet and not returned, then they may still be sitting there on a table, untouched. And if a nuclear reactor was half built and the crane was placed in the correct place to lift part of a wall tomorrow, it is still there.

Chernobyl was intended to have ten reactors in all, and to be the largest power station in the world, providing power for much of Eastern Europe. At the time of the accident, four were operating. The disaster occurred in the newest of these, reactor number four. Reactors five and six were under construction at the time, and these were the first that we approached.

Reactors five and six are frozen in time. They are construction sites of buildings that are half complete. The cranes on top seem in the middle of a job. Even if a construction job is abandoned, cranes are not normally left suspended about them, as cranes are valuable and useful elsewhere. Here, though, the cranes are radioactive and dangerous, so nobody has been near them in more than 20 years.

For us, though, the radiation level was getting higher, and it was demonstrated that it was significantly higher in the soil and vegetation than inside the bus.

In the distance, though, were reactors one through four. Reactors one and two were closest. We stopped some distance from them, next to one of the canals that brought the immense amounts of water necessary for a power station complex of this magnitude from the nearby Pripyat river. We stood on a bridge across the canal and looked at the large number of fish swimming in the water below. Jokes were made about how a few would be caught so we could eat them for lunch.

We looked at reactors one and two. These were the oldest reactors, and (like reactor three) they continued operating for some years after the disaster at reactor four. A huge amount of capital had been invested in them, and Ukraine needed the electricity. So they ran, reaching the end of their useful lives in 1996. Reactor four was shut down in 2000, before reaching the end of its useful life, under pressure from the US government, amongst others, principally because the sentence “The Chernobyl nuclear power plant is still operating” was enough to give panic attacks to half the world.

The most important thing to notice is that these reactors contain no enclosing protective domes as nuclear plants typically do in the west. When an American reactor at Three Mile Island had a partial meltdown in 1979, the radioactivity was successfully sealed from the atmosphere, and the disaster was fully contained. Soviet reactors were built with less resources and with safety much less in mind, so no domes.

Next to reactors one and two was a truly immense electrical power distribution system. When they said this was a huge power plant, they weren’t kidding.

We drove around the reactor complex, to reactors three and four. We were not permitted to take photographs of the military fence, but were assured that we would get a close view of the reactor a litle further on.

Which we certainly did. We were brought to a viewing area next to a memorial, no more than a couple of hundred metres from the remains of reactor four.

This is it. This is the remains of the worst nuclear disaster in history. This is the site of what is somehow one of the more iconic places of the events of the time I have lived in. When that event happened, I wouldn’t have imagined I would get so close a mere two decades later, and I am not sure if the nuclear disaster or the Soviet Union was the more forbidding thing.

We spent some time near the remains of the reactor: simply looking at it; reading the words on the monument; taking one another’s photographs in front of it; looking at readings on Geiger counters that were not especially dangerous in the short term, but you wouldn’t want to spend weeks there.

Unfortunately, the photograph of me in front of reactor number four is just about the worst photograph of me ever taken, and even with my legendary lack of vanity about my own appearance, I will not embed it in this page. This is a shame, given there will probably never be another photograph of me in such an extraordinary place.

Shortly after the accident, reactor number four looked like this:

Shortly after the accident, it was enclosed in a structure called the sarcophagus. Information is vague about the subsequent health of the people who built it. However, it was not particularly strong, and additional construction and strengthening work has taken place in recent years to prevent it from collapsing. It still looks nothing like how you would imagine a western nuclear power plant to be, before of after an accident.

There was not terribly much to be said. We just stood for a time and looked. There was, however, more to see. Most particularly the city of Pripyat.

As I have recounted, Chernobyl was the nearest town to the site of the power station when the station was planned. However, it was not nearly big enough or close enough to house the approximately fifty thousand workers necessary to built and operate the plant. In any event, the power plant was a Soviet model project, and it needed a Soviet model city close to it to support it. Pripyat was built, named after the local river.

When the accident occurred,the level of contamination was highly variable depending on direction. A fair bit went in the direction of Pripyat, and to get there we had to cross the directly downwind path of contamination. We were told that we were about to visit the most radioactive place on the whole trip. Geiger counters were brought out, and we watched the numbers double, triple, and quadruple, to a level far higher than we had seen near the reactor itself. Out the window we could see overgrown grass fields. It was clear nobody stopped here for trivial reasons. We drove through. It was clearly not a place for a roadside picnic.

Soon, though, we were in Pripyat. In some ways it was like the other, smaller towns we had visited. Buildings were overgrown with vegetation, but there was still some structure to the vegetation. Avenues through the trees were still there, and could be passed through with some effort.

The buildings were taller than in the other towns. I have visited a few Soviet and other Warsaw pact towns in my time, and this had clearly been a nice one, as they went. The people who lived in it were once no doubt proud of it, and proud of what they did.

Our first stop was a school. Here, more dramatically that anywhere else on the trip, we were exposed to the combination of lengthy decay and rapid abandonment. Pripyat is interesting in the same way that Pompeii is interesting. An outpost of an ancient and otherwise destroyed culture was suddenly abandoned there, and is preserved for modern view. Pripyat is mostly residential buildings, and these have apparently been fairly comprehensively looted. However, schools are of little interest to looters. However, they are of great interest to anthropologists, because as New Labour and Barack Obama know well, they are amongst the chief centers of indoctrination.

Although the school contained a lot of broken glass and fallen over bookshelves and broken walls, it also contained a remarkable amount of preserved life. Books that could still be read. Blackboards that could still be read. Chemistry tables. And more Soviet stuff. Ideological lectures. Portraits of Lenin. Portraits of good Soviet citizens standing in front of the factories.

We were taken to a room in which English language classes had taken place, and there was lots of surviving teaching materials. I have never encountered a set of school or government provided foreign language learning materials in my life that did not attempt to simultaneously teach an ideological agenda, and those of the Soviet Union were somewhat predictable, talking about the US and UK from a class viewpoint, and painting the United States as a nation of warmongers intent on creating a world holocaust.

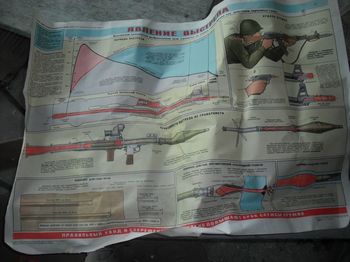

Next we were taken to a room full of gas masks and protective clothing, images of guns, tanks and aircraft, and a place where safety drills and precautions were taught.

This had nothing to do with the fact that we were only a few kilometres from the worst nuclear accident in history – this was the classroom where children were taught military skills in order to perform their assigned role in the third world war. The proximity to the catastrophe made it profoundly creepy however.

In truth, the whole school was perhaps the oddest place on the whole excursion. I wandered around it for a time, lost in thought – sufficiently so that I failed to notice that the rest of my party had left the school. After a time, our official guide and minder – the gentleman in fatigues – came back into the school and gestured that I should return to the bus, where I found the rest of the party waiting for me.

Next stop was a sports centre. Huge indoor pools with diving board – basketball courts. The emphasis seemed to be on Olympic sports. Not surprising, given the history of the USSR. Once again, these had once been fine facilities. A model town. Atoms for peace. Superior athletes being created by a superior system.

Then we went to an abandoned amusement park. The decrepit Ferris Wheel is perhaps the iconic image of Pripyat in its many pop-cultural references. There is no health and safety crap here, although one perhaps wishes there had been a little more to apply to the people running the power plant in 1986. Somebody from another tour party visiting at the same time climbed halfway up it to pose for a photograph.

The amusement park surrounding the wheel is quite large. (Once again, model town). Dodgem cars. Rotors.

A small boat shaped seat from one of the other rides, sitting on the pavement.

Photographs of the same place taken by other people five, or even ten years ago show the same boat sitting in the same place. One can imagine few other places on earth where such a thing would remain in the same place, untouched, for so long. Once again, the sense of Pompeii.

There was one final desination before leaving Pripyat. We went into one of the larger and more structurally sound buildings – a civic structure of some kind. Perhaps a hotel. Perhaps a municipal or office building. We went up a few flights of steps onto the roof. There was fine view of Pripyat, and, more importantly, the nuclear power plant in the distance. Sergei let his imagination run away with him a little more, explaining that nobody really knew what was going on inside the power plant. Perhaps another reaction would occur, and another disaster – even a nuclear explosion. Some things work better in computer games than reality, but the weirdness of the place does give a sense that anything is possible. He expressed his thoughts about how the whole idea of nuclear power was questionable. I didn’t really agree – the Chernobyl accident was caused by appalling safety standards and horrible design, other sources of energy aren’t necessarily safe, and I am more inclined to blame the Soviet Union than nuclear power per se – but I had to concede he had a certain justification for feeling this way. In the Ukraine, nuclear power had led to something terrible. And looking at Pripyat and the Chernobyl plant was profoundly unsettling. This is a deeply unnerving place. For people who are inclined to nightmares about the 20th century, this is one of the exhibits.

However, the tour was more or less over. We returned to our bus, and drove back to the town of Chernobyl. We returned to the building where we had signed our disclaimers earlier. Here we put our hands on a small radiation detector to determine if we were more or less clean, and entered a dining room. I asked Sergei what would have happened if I had not been clean, and his answer was “Not very much”. We were served an excellent and quite leisurely Ukrainian meal of about five courses. Probably half of the people in the room were tourists, and the other half were guides, military people of different kinds, and people who had other business in the Zone. The mood in the room was quite warm and jovial. People in the middle of a day’s work were enjoying a good lunch. Human nature is universal, and the weirdness of the place and of the jobs did not change this. No attempt was made to sell us anything, which makes me thing, once again, that this is a relatively immature tourist market.

Lunch over, we headed south. At the edge of the Zone, where we had had to present our passports on the way in, we were required to disembark from our bus to once again be checked for radiation. This time, we had to enter a fully body detector. As it happened, I was the only member of our party who triggered the radiation detector. I tend to think the rest of the party were almost pleased that someone had triggered it so that they could see the consequences.

On the other hand, I was Radioactive Man, and I was perhaps personally less pleased. However, as Sergei had told me earlier, not a great deal happened, I walked back outside, and some blokes in uniform washed my shoes. After that, I once again entered the radiation detector, and this time I did not set it off and I was allowed to leave The Zone.

We then drove back to Kiev. On the bus back, the Czech member of the touring party told me about his stop in Odessa on the way up, and urged me to go there on the one full day I had left in the Ukraine. It would be easy enough. I could get the overnight train, then spend the day in Odessa, and then get the overnight train back. My thought in response to this was that I am not as young as I used to be. Just finishing his commentary, Sergei told us about his future hopes for expanding his tour company. Apparently he was just about to gain approval to run tours to an abandoned Intercontinental Balistic Missile silo south of Kiev. The USSR has left interesting and horrifying ruins.

Another for next time, perhaps.

Another cracker of an article, Michael.

Fascinating post.

I’ve recently been to the DMZ, but I must confess that it never occurred to me to visit Chernobyl… when I finally get to Kiev I will certainly try to go there. Beats a beach in Thailand…

Nice post Michael I really enjoyed the photos its somewhere I would really like to see myself.

I remember the old Woodpecker/Steel Yard/Duga 3 for the grief it used to cause me. Back in the early 80’s I built a short wave radio for my O level electronics qualification. When I turned it on with just a screwdriver as an antenna the first thing I heard was the flaming Woodpecker tapping away. I always imagined half the power generated by Chernobyl was used up by it. Since the cold war ended I have kept an occasional eye out for academic papers or other technical descriptions of that radar and its capabilities but have never found anything. Odds on it never worked properly anyway !

Once again, the journalism we don’t get elsewhere.

The photos remind me of where I’m living. Much of the cities in the US are like them.

Different disaster, similar results.

There is a following for ruins about us. “Urban spelunking” “urban invasion”, “urban exploration”

who seem to be getting there before both wrecking balls and archeologists.

The entire street and apartment I’m in, were built in 1939. Using new technologies, owners ignore the old and paint over it. As with people.

Absolutely fascinating, Mr Jennings – your picture of Duga 3 does give me a greater sense of creepiness than the other pictures do. I don’t quite know why.

The aesthetics in your description put me in mind of the old smelting works in Duisberg, Germany.

Yes, fascinating. Thank you, indeed. Touches a deeply responsive nerve perhaps from being born next to an experimental nuclear reactor. Sort of mother figure. Strange places where marshes and industry meet on the edge of time. Can stand there for hours.

@Michael. Concerning your disc crash problem, I have some modest suggestions. Please let me have an email address, as yet another blog comment registration is just too much.

Best regards

If anyone is going to be able to recover your data, it’s these guys:

http://www.ontrackdatarecovery.com/

Not cheap, but about the best in the world you can find in my experience (as an IT professional).

Fascinating stuff. “Zone of Alienation”, I loved that, it sounds like emos and Morrissey fans should live there. I also didn’t know that we should really call the disaster site after Vladimir I Lenin; appropriate that that murdering bastard should have had the exploding reactor named after him, the only good thing he ever did was die of the pox.

That’s a very moving memorial sculpture.

Indeed. Thanks Michael.

Astounding. I can’t imagine Mrs. Wh00ps going for a holiday in the Ukraine, but should I ever get divorced I’ll be right there; I love all that abandoned spooky city stuff! And the history too… I have only dim childhood memories of the incident (accident?) but it’s always left an impression on me.

Quite an interesting article and great photos!

Michael, you did a superb job of reporting, Years ago, not long after the Chernobyl incident, I read a book giving a whole account of Chernobyl. I have dreams of finding still alive a man among the many who were brought from the explosion site to the hospital nearest the accident. This man I simply want to give a gentle hug. In the hospital he was lain onto a bed. Nurses and other hospital staff were dashing hither and yon doing the best they could to help everyone, but they certainly weren’t one-on-one in relation to victim workers. In one bed lay a man who watch the feverish activity that was aiding his fellow workers and, not wanting to take time away from the help being given and in needing to go to the restroom, he struggled to sit up on the side of his bed and when he succeeded, the skin on both of his legs slipped from his knees to down around his ankles. That man is a man above men to my way of thinking.

I have added to my long list of places to visit though I certainly would not render the experiences as well in photographs and words. Thanks Michael.

What an amazing and fascinating account.

Thanks Michael.

Michael, when you said “roadside picnic”, was it intentional?

May 1st 1986 was a regular Soviet holiday, with multi-million -people demonstration and parade planned. Authorities knew what happened 4 days before in Chernobyl, and of the radioactive cloud that went towards Kiev. The demonstration was not canceled. Residents were not told about the disaster. There was nothing on the news on Soviet TV for at least a week since April 26th. Then there appeared a short and foggy official announcement about a “contained incident” and recommendations to residents in 100km zone were given: don’t open your windows (in May!), give your apartment more wet-rag cleaning than usual, wash fruits and vegetables thoroughly. That’s it. There was no adequate information whatsoever , so rumors started circulate, sometimes really wild ones. About possible nuclear attack on reactor, and hundreds of thousands of people arriving into hospitals burned, dying from radiation, of massive spike in skin and thyroid cancers, etc. Geiger devices were sold on the black market and iodide disappeared from drugstores.

One small note to your excellent post, Michael, re: the military education classroom you have seen. This class was not intended for making perfect little soldiers out of schoolchildren; it was called “Civil Defense” course, and largely contained information relevant to the topic. Of course, as all subjects in Soviet school, it was politicized (you should read the Contemporary History textbooks, for real fun), but no more so than others.

I hated it, mostly because the students were expected to assemble/disassemble Kalashnikov in set # of minutes (3? 4? don’t recall) and try on gasmasks (which were leaking and smelled horribly). But it did gave us some skills helpful to resist panic and act in organized manner in case of global-scale event – which sadly, American shoolchildren are not taught and which would come handy on 9/11. I’m told the civil defense classes were taught in US in the 50’s and 60’s – I think the practice should return now, updated, of course, with information relative to sources and tactics of contemporary terrorism.

I was present in both events, as it happened.

Great article Michael!…Scary to think that the UK have approved construction of up to 10 new nuclear power stations by 2020!!

Before moving to Australia I purchased a book entitled “The Nuclear Barons” ~ Peter Pringle from a second hand bookshop in Whitby in Yorkshire, a great read.

A great insight into nuclear issues on all levels.

Michael, when you said “roadside picnic”, was it intentional?

Of course. Our guide Sergei did observe that this was not a place to stop for a picnic when we passed. I don’t think he was making a cultural reference, but I couldn’t resist doing so myself.

Michael, it would be interesting to learn how many people on this thread, besides me, caught your reference. Besides the gamers.

I didn’t – still don’t, as a matter of fact…

Alisa, click on the link in my first comment.

Got it – thanks:-)

I didn’t get the reference either, until I read the link. I guess my SF knowledge base is deficient.

Tatyana, interesting post; thanks. FWIW, I was in school in the US in the 50’s & 60’s, and while we did have something considered “civil defense” training, it was nothing like what you describe. Ours consisted primarily of being instructed to crouch down under our desks (or, sometimes, outside in the halls) with one hand over our eyes and the other over the backs of our necks (don’t ask me why!), in preparation for the expected nuclear attack. Nothing remotely as useful as learning to break down an AK-47 (or M-16 or M-1). Those of us who weren’t terrified by the exercise considered it a total waste of time (albeit a nice break from class).

Duck-and-cover.

Laird,

Don’t feel bad about not spotting the reference; it is mostly known to us post-Soviets, scattered in the world as we are. Although Strugatski’s insight manifests itself in mysterious ways, long after their novels were written; Chernobyl is but one in many.

A friend pointed, just a few days ago, to this news item(Link) and recalled their novel “Definitely maybe(Link)” (Russian title “A billion years before the end of the world”).

The Civil Defense course was taught, if I recall correctly, in the 9th grade (10th being the last in school before college). There was lots of nonsense in curriculum, too – like studying the kinds of gases used in WWI (still remember, by heart: zarin, zoman, iprit, fosgen, etc – sp?) , or marching in shoolyard in formation. But there was also make-belief “Alarm drills” (of various intensity), we learned by heart the points on the map where to go in case of emergency, the first aid for various WMD-symptoms. Besides AK-47, I think we were supposed to know an Izhevsk rifle: I failed at both. Mostly because I was scared of our instructor worse than of nuclear war; he was a retired Infantry Captain, with coordinated vocabulary and manners. In the shooting range we had at school’s basement I managed to point my AK-47 at him instead of on target…that was the first time in my life I was called Mademoiselle, but accompanied by such flattering epithets that my shocked mind blocked them from memory entirely.

Ah, good times, as a friend is fond of saying.

LOL! Easy with that rifle, Mademoiselle:-)

I only finished 6 grades before I left, so I didn’t get to these classes in school, but I remember having a short course in one of the summer camps, with gas masks and mock emergency kit (the anti radiation, chem and bio attack shots etc.). I was either 11 or 12. No weapons though – the first time I both saw and used one was in Israel when I was 14. And don’t laugh, that thing is pretty accurate – beats the Uzi hands down:-)

I think Tatyana actually does understate the regard in which the Strugatsky brothers are held in the west. Roadside Picnic remains in print in English 35 years after being first translated, and most serious Science Fiction readers in English know of and have read some of the brothers’ work. Their appeal in English is probably to a narrower audience than in Russian, but within that audience they are greatly respected.

Glad to hear that, Michael.

So what do you think of the coincidence? Did Nilson and Ninomiya have read Strugatsky’s?

Wiki: mathematician Vecherovsky (ВечеровÑкий). He posits that the mysterious force is the Universe’s reaction to the Mankind’s scientific pursuit which threatens to discover the very essence of the Universe. This reaction is what prevents development of “super-civilizations”, ones that would be able to counteract the Second law of thermodynamics on a cosmic scale.

Time: Bech Nielsen of the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen and Masao Ninomiya of the Yukawa Institute for Theoretical Physics in Kyoto, Japan, have published several papers over the past year arguing that the CERN experiment may be the latest in a series of physics research projects whose purposes are so unacceptable to the universe that they are doomed to fail, subverted by the future.

Hi Michael,

What was the name of Sergei’s tour company? Am looking to organise a similar tour with a bunch of mates in Autumn ’10 and could not find a reference to it above.

Cheers!

NrG

You can visit it with our tours^ Chernobyl tour and AK-47 shooting tour. (Link)

[Editor: normally I would delete this as spam but it is just too… perfect… for the original post 🙂 ]