Democracy tends towards protectionism when those harmed by free trade are numerous enough to count. But democracy also demands cheap goods. No one has yet squared that circle.

|

|||||

|

What’s more, the imposition of punitive tariffs on poorer countries like Vietnam will simply impoverish rather than improve the potential importing power of these countries. Disrupting the economic development of poorer countries isn’t going to improve the chances of selling to them. The irony is brutal. Trump’s fixation with trade-deficit “offenders” is punishing the very nations that could one day erase those deficits through development and prosperity. US consumers, businesses, and economic growth will all suffer as a result of the US president’s inability to grasp this elementary logic. There seems to be just one long-term strategy behind all this: unleash populism for immediate electoral returns, blame someone else for the problems that populism inevitably causes, and let someone else deal with the long-term consequences. “Perhaps the greatest paradox of all is that parts of the Maga movement are embracing a form of Right-wing wokery, with their own dark conspiracy theories, cult of victimhood, identity politics, denial of reality, moral grandstanding, hypersensitivity and purity tests. “In this vein, whingeing about trade deficits deserves to be dismissed as critical trade theory’, as Trumpian corollary of critical race theory: it postulates, nonsensically, that any shortfall must be caused by unfair practices, oppression or historic injustice. The ‘woke Right,’ a term coined by James Lindsay, is almost as much of a turn-off as the original Left-wing variety.” – Allister Heath, Daily Telegraph (£) He gives Mr Trump high marks on taking the fight vs DEI, some of the DOGE cuts (with a few caveats), and on energy policy (which in my view is Trump’s ace in the hole). But the broader point Heath makes about where he thinks Trump/Maga is losing it, including this nifty term of Heath’s, “critical trade theory”, is absolutely spot-on. It is, in my view, one of the big blinds spots of today’s populist Right and threatens to undo the good things that a Trump 2.0 might achieve, which would be bad not just for the US, but the West in general. As Heath goes on to write (and remember, he’s a pro-Brexit, free market chap, and not some obdurate Never Trumper), a course correction is needed. And Trump is not incapable of it. As you can imagine, there have been a lot of attempts to make sense of what Mr Trump is trying to do about tariffs. As of the time of my writing this, the dollar is coming under pressure, Mr Trump appears to be ratcheting up the tariff war with China to even higher levels, and there are signs that a few of his allies are getting nervous (seriously, how on earth can he have people working in his government such as Elon Musk and Peter Navarro who talk to each other in this way?) One way to think about the the US/rest of world imbalances is that this is about production and consumption. In various ways, countries such as Germany, Japan and China produce a lot, and tend to be careful on how much they consume; on the flipside, the US loves to consume. As Joseph Sternberg in the Wall Street Journal puts it:

This is an interesting point about the control of credit and yes, Net Zero, intersecting in ways that suppress consumption and encourage production, much of which has to go overseas – to places like the US. Sternberg continues:

So what has the US been doing to encourage consumption?

And as the writer says, the “root-cause” solution to the trade deficit issue, to the extent that it is a problem that governments should address, is to rebalance – get rid of consumption subsidies and stop penalising production. That means, for instance, rolling back regulations, zoning laws, etc. (To the limited extent that this is being done by Trump, that is a mark in his favour.)

This the key. Social Security and other big entitlement programmes in the US are, as they are in the UK and much of the West, popular with ordinary voters; and the voters who switched from the Democrats to Republicans in 2016 and 2024 aren’t going to be happy to see these programmes reformed or reduced. It is therefore easy to see why tariffs are a tempting technique – it is easier to go on about those naughty, over-producing Asians and Germans as being at fault, rather than because incentives are structured as they are. Sternberg concludes:

The problem, however, is that entitlement reform is very hard to do, politically. There are some things that will also be politically tough: not everyone likes deregulation, given how occupational licensing and so on often shields vested interests. (Think of how the London mayor tried to hit Uber, at the urging of the traditional taxi sector, a few years ago.) Zoning laws are a problem but they are also supported by people who want to protect the value of their properties, as they see them, and so on. In certain countries, the planning system is so convoluted that it is a major brake on production. Fixing all this takes political will and the risk of antagonising vested interests.

As Matthew Lynn, a columnist writing in the Sunday Telegraph (£) puts it, the compulsion on car firms to build more electric vehicles (EVs), on pain of large fines, was already causing great damage to the UK and European economy. With the US now imposing blanket 25% tariffs on car imports from the UK, the Net Zero obsession is suicidal for the UK-based car industry, home to brands such as Jaguar Landrover, which has just paused shipments to the US:

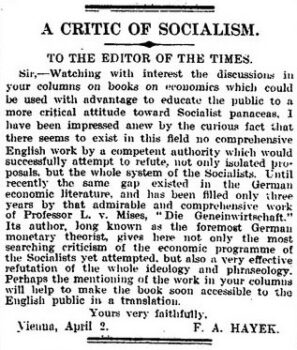

Tens of thousands of car workers could lose their jobs, unless there is a drastic change in policy in the UK – never mind what the Trump administration chooses to do – and they live in those famed “Red Wall” seats that the insurgent new party, Reform, is targeting at the next General Election. [a] trade imbalance is not an inherently bad thing. it can be a very good thing, a beneficial thing. this idea that if we buy $50bn more goods from kermeowistan every year than they buy from us that it implies that they are somehow “taking advantage” or this this is “unstainable” or negative is flatly false. it’s actually ridiculous. it ignores complex trade flows and balancing factors like “capital flows.” people really seem to struggle with this, but it’s not that difficult. you’ll will have a large lifetime trade deficit with the grocery store. you will buy much from them. they will buy nothing from you. is this a problem for you? is it unsustainable? most people seem to sustain this beneficial grocery trade their whole lives. why is it any different if it crosses a border or gets aggregated by nation? (spoiler alert, it’s not) you’ll likely run a lifetime trade deficit with many countries too. you buy a BMW. that’s a deficit to germany. you run a restaurant in toledo. you have no german customers. does this fact harm you in some way? did germany take advantage of you? would it be better for you if we imposed a tax that made that BMW 25% more expensive? no, and if we do, it might create automotive jobs in the US, but the cost to do so is YOUR choice and your budget. Follow the link, read the whole thing. Well, he went ahead and did it. In a ceremony outside the White House, Donald Trump unveiled a list of tariffs on countries, on “friend and foe”, starting with a minimum of 10% (the UK, which is now outside the European Union, was hit with the 10% rate, while the EU was hit with double that amount). In general I see this as a bad day for the US and world economy for all the sort of reasons I have laid out. This will not adjust the worldview of the red hat wearers, but I wonder has it ever occurred to Mr Trump’s fans that his arguments, when adjusted for a bit of rhetoric, are more or less leftist stuff from the 1990s? Ernest Benn was the uncle of Tony Benn and great-uncle of Hilary Benn. Luckily for us he was the black sheep of the family and pursued a career in business before becoming one of the “great and the good”. And then he decided he didn’t want to be great or good any more, founding the Society for Individual Freedom. As I understand it the Libertarian Alliance – who most here will be familiar with – emerged from that association. A hundred years ago Benn was compiling a list of good economics books which – seemingly unbelievably – The Times published. It includes – as you might expect – Smith, Bastiat and Mill and – as you might not expect – Spencer and Smiles. It also includes Henry Ford – presumably before he started blaming the Jews for everything. But there is one book that’s missing. Luckily a young Austrian is on the case. [I hope this is legible. It’s a bit blurred on my computer but the original is fine. The list is totally blurred if I try to include it inline with the post. All very odd.] Elliot Keck (who he?) had this recent excellently sharp item over at CapX:

“America doesn’t make anything anymore” is a powerful talking point, but it’s false. We make plenty, including some of the most complex, high-valued goods in the world, from aircraft to pharmaceuticals to advanced electronics. Our workers don’t make many T-shirts or toasters; other countries can do it more cheaply. And the more successfully we produce and export advanced machinery, the more foreign goods we can afford to import. America’s industrial base is not collapsing. It’s evolving—becoming more productive, more specialized, and more capital-intensive. Protectionism won’t bring back the past or revive old jobs. It will just make the future more expensive and shift workers into lower-paying jobs. – Veronique de Rugy, Reason magazine. Lest any Trump admirers get all upset about my posting this quotation it is worth pointing out that there is plenty of protectionist guff on my side of the Atlantic as well. The EU has its Customs Union – the aspects of the bloc that I like the least – and it is described in typically bureaucratic fashion, here. This article in the Financial Times contains the claim that the EU is not as comprehensive in its “protective shields” as the US, Canada and Australia. That said, free trade in general terms is in global retreat, unfortunately, and not simply under the Trump administration – previous US governments were hardly much better, although that is not setting the bar very high. I have jousted a bit in the comments on previous threads with those claiming that tariffs are necessary, for various (and to my mind, fallacious and often self-contradictory reasons): to “protect jobs”; national security and diversification of supply; as a club to hit supposedly foolish and oppressive other countries; to raise taxes and shift away from income taxes, or that comparative advantage on the David Ricardo model does not work if you allow cross-border capital flows. All the arguments are, in my view, flawed and in some cases, just plain wrong. (Here is a good summary of the arguments contra protectionism.) As it is used a lot these days, here’s a good take-down, from the Hoover Institution, of the “national security” argument for tariffs. I can also recommend a new book, Free Trade In The 21s Century, a collection of essays by folk from the political, business and economics world. It is a big read, but good to immerse in if you want to delve into the arguments. What I see playing out today in the US – and at times in Europe – is the way that, since the end of the Cold War and the supposed triumph of free market ideas in the subsequent 20-plus years, the argument was not made with sufficient force and the benefits not adequately spelled out. So here we are. And one big problem is that what Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter called the “creative destruction” of capitalism meant that the supposed losers of all this commotion, such as car workers in the UK West Midlands or the US “rust belt” did not get, as far as they could tell, much immediate uplift from the greater overall prosperity that open trade brought. Telling them to “learn to code” just riled them up. (Explaining to an unemployed coal miner or machine tool operator that they should learn a very different skill is difficult, at any age, but particularly if the argument comes from a politician who appears to have never had a real job.) And this, it seems to me, is the fundamental issue: how can a culture of adaptability and can-do attitudes be fostered in a world of constant and at times, disturbing change? (Robert Tracinski makes a good attempt to do so, here.) Because if that does not happen, the populists of the left and the right, whether a Trump, a William Jennings Bryan, etc, will energetically seek to fill the market void. (HL Mencken magnificently destroyed Bryan, who was an opponent of gold-backed money and held many other terrible views that are, I fear, still popular in certain quarters.) This book, Capitalism In America, from a few years ago by journalist Adrian Wooldridge and former Federal Reserve chairman, jazz musician and economist Alan Greenspan (full disclosure: I have met both of them), gives a good overview of the rise and fall and then rise of arguments about free trade, globalisation, the problems with how the losers from disruption can demand destructive changes, and more. If advocates of free trade like me cannot explain all of this, then the protectionist argument will gain ground, to calamitous effect. Defining the benefit of spending as who gets the money rather than what gets bought is economic insanity. We might have a little insight there as to why government control of the economy ends up impoverishing. Those business journalists at Bloomberg ($) have noticed that some investors are betting that Russian debt – a market frozen since the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine – could “thaw out” if there’s a ceasefire/peace deal. But this is a gamble that has potential to go very wrong.

Given the potential for things to go awry, such as if Mr Putin treats a pause in the fighting to re-group and launch another assault, I’d want to be in close touch with any investment managers running my savings plans to be sure that Russian debt, assuming it was ever to be considered in a portfolio, were to take up more than a few percentage points of my total holdings. In fact, I’d want to insist that Russian debt, even after any sort of diplomatic move (regardless of how it is arrived at), is out of bounds. |

|||||

All content on this website (including text, photographs, audio files, and any other original works), unless otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons License. |

|||||