We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

I was responding to a comment under this article… when it struck me: why do so many people find this screamingly obvious fact so bloody hard to figure out?

“The banks stole our money. If you are not banker, that includes you. The banks stole from everyone – businesses, countries, citizens.”

No, the politicians who bailed them out with taxpayer money stole ‘our’ money after they created the moral hazard that led to the banks doing the things that they were given the incentives to do.

In a sane world, said bankers should have simply been allowed to go bust… so the problem is not ‘bankers’, it is the people who refused to let the bastards go broke by giving them third party… taxpayer… money.

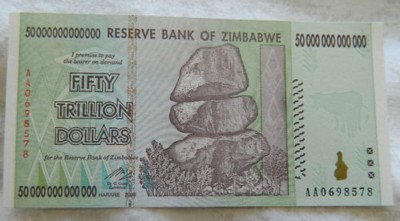

Andy Janes has just bought one of these:

He paid £1.70. Not bad. But how many pounds will such a thing cost in a few years time?

Have a nice weekend.

I came across this good collection of messages via Tim Sandefur. “We are the 53 per cent” puts my sentiments across exactly.

I don’t want to sound overly harsh; some of the Occupy Wall Street people, as Brian Mickelthwait notes, might have some decent views and with a bit of outreach, could be helped to understand the statist dimension to our current problems. But I am afraid that with a lot of them, I tend to share the scornful analysis of George Will.

Talking of those who feel they work too hard to spend their time protesting, there are echoes of Sumner’s “Forgotten Man”.

Instapundit chooses the first few sentences of this piece about the Occupy Wall Street … thing, to recycle. But my favourite bit is where George Will summarises the OWS position:

Washington is grotesquely corrupt and insufficiently powerful.

I also agree with the following comment, which was attached to this:

The reason why these occupiers are getting so much attention is that the mainstream media think they’re not idiots and are advertising them, and the right wing alternative media know that they are idiots and are advertising them.

Which says part of what George Will said, and which I agree with because I wrote it.

It is, when you think about it, easier to write about something that is rather small. When you encounter an OWS event, you can listen to anyone there who wants to say anything in about ten minutes. Compare that with working out what the hell everyone thinks at a Tea Party get-together. To do an honest job on that you have to be there for hours.

But then again, these protesters are not, perhaps, all of them, complete idiots. They are very right that things have gone very wrong.

We’re due an OWS copycat demo here in London this weekend. Someone called Peter Hodgson, of UK Uncut, is calling for, among other things, “an end to austerity”, by which he means him and his friends keeping their useless jobs for ever. Good luck with that, mate.

There is actually some overlap between what some of these Occupy London characters may or may not be saying this weekend, and what my team says about it all.

Laura Taylor, a supporter of the so-called OccupyLSX, said: “Why are we paying for a crisis the banks caused? More than a million people have lost their jobs and tens of thousands of homes have been repossessed, while small businesses are struggling to survive.

“Yet bankers continue to make billions in profit and pay themselves enormous bonuses, even after we bailed them out with £850 billion.”

It’s like the Tea Party in Britain is too small, and has to climb aboard Occupy London. Well, maybe not, because Laura Taylor neglects to mention the role of the world’s governments in setting the various trains in this giant train-wreck in motion. Who caused the banks to cause this crisis? That’s what my team wants to add. The banks were only doing what the politicians had long been incentivising them to do, and the banks are doing that still. The banks are only to blame for this mess in the sense that they are now paying the politicians to keep it going. But that is quite a big blame, I do agree.

So anyway, the British government, like the US government, is now also grotesquely corrupt, and it should jolly well pull its socks up, its finger out and itself together. And then be hung from lamp posts.

Seriously, I remember back at Essex University in the early 1970s how the Lenin-with-hair tendency thought that the answer to every problem in the world then was to occupy something, fill it with rubbish and then bugger off and plan their next stupid occupation. They were tossers then, and they, their children and their grandchildren are tossers now. Farce repeating itself as farce.

Maybe I’ll dress up (as in: down) in shabby clothes and sandals with no socks (which I would never dream of doing normally) and join in, with a camera. Although, I promise nothing, because this weekend there is also the Rugby World Cup semi-finals to be attending to.

Somehow, this man, Eoin, appears to be so thick (he’s a Doctor, apparently) that I fear he should be banned from handling heavy machinery:

“We are taught by Cameron to regard small businesses as the engine room of entrepreneurial spirit in the UK. We are led to believe that their inventions, wealth creation and profits lead to employment and growth. But this is the stuff of fantasy. Three quarters of the 4.5million businesses in the UK employ no one. Their wealth creation serves their own ends. They create no jobs and do nothing to solve youth unemployment. The vast majority of small businessmen are in business for themselves. Evidence of civic virtue or a desire to create jobs is in preciously short supply and thus Cameron was wrong to shrug off record rises in youth unemployment as something that could readily be solved by small business.”

So my wife, for example, who set up her own business (marketing for SMEs) has done nothing to reduce unemployment. So all those people who, for example, lost a job at a firm and who set up on their own are not doing anything to reduce unemployment unless they employ someone? Is this man for real?

Of course, given the job-destroying impact of red tape, employment protections on full-time and part-time staff, taxes, and so on, it sometimes is a marvel that anyone ever gets a paid job at all. I am a minority owner, and employee, of a small business in wealth management/media sector and every decision on hiring someone is taken with the utmost care, since it is difficult to fire someone if they are not up to scratch.

There are times when I fear that some people out there are so fucking stupid that Darwinian ideas of natural selection are in need of revision.

Thanks to Tim Worstall for spotting this piece of lunacy.

Yesterday afternoon, I attended the meeting at the House of Commons that I flagged up here a few days earlier. It was a fairly low key affair, attended by about thirty people or more. Not being a regular attender of such events, I can’t really be sure what it all amounted to. Things happen at meetings that you don’t see. Minds get changed, in silence. Connections are made, afterwards. You do not see everything.

But what I think I saw was this.

The first thing to clarify is that this was the Detlev Schlichter show. Steve Baker MP was a nearly silent chairman. Tim Evans was a brief warm-up act. Schlichter’s pessimism about the world economy was the heart of the matter. He did almost all the talking, and I believe he did it very well.

It’s not deliberate on his part. Schlichter just talks the way he talks. But his manner is just right for politicians, because he doesn’t shout, and because he so obviously knows what he is talking about, what with his considerable City of London experience, and that flawless English vocabulary spoken in perfect English but with that intellectually imposing German accent. He foresees monetary catastrophe, but although he has plenty to say about politics, and about how politics has politicised money, he is not trying to be any sort of politician himself. Basically, he thinks they’re boxed in, and when asked for advice about how to change that, he can do nothing beyond repeating that they are boxed in and that monetary catastrophe does indeed loom. But what all this means, for his demeanour at events like this one, is that he doesn’t nag the politicians or preach at them or get in any way excited, because he expects nothing of them; he merely answers whatever questions they may want to ask him. He regards them not as stage villains but as fellow victims of an historic upheaval. Despite the horror of what he is saying, they seem to like that. He didn’t spend the last two months cajoling his way into the House of Commons. He was simply asked in, and he said yes, I’ll do my best.

Present at the meeting were about five MPs, besides Steve Baker MP I mean, which is a lot less than all of them, but a lot more than none.

One, a certain Mark Garnier MP, seemed to be quite disturbed by what he was hearing, as in disturbed because he very much feared that what he was hearing might be true. Mark Garnier MP is a member of the Treasury Select Committee, which I am told is very significant.

Another MP present, John Redwood, was only partially in agreement with Shlichter. He agrees that there is a debt crisis, but doesn’t follow Schlichter to the point of seeing this as a currency crisis. In other words, Redwood thinks we have a big problem, but Schlichter thinks the problem is massively bigger than big.

Redwood was also confused by Schlichter’s use of the phrase “paper money”, by which Redwood thought Schlichter meant, well, paper money. Redwood pointed out, quite correctly, that paper money that has hundred percent honest promises written on it, to swap the paper money in question for actual gold, is very different from the paper money we now have, which promises nothing. Redwood also pointed out that most of the “elastic” (the other and probably better description of junk money that Schlichter supplies in the title of his book) money that we now have is mostly purely virtual additions to electronically stored bank balances. We don’t, said Redwood, want to go back to a world without credit cards or internet trading! All of which was immediately conceded by Schlichter, and none of which makes a dime of difference to the rightness or wrongness of what Schlichter is actually saying; these are mere complaints about how he says it. Such complaints may be justified, given how inexactly “paper money” corresponds to the kind of money that Schlichter is actually complaining about. But Redwood seemed to imagine that what he said about what he took “paper money” to mean refuted the substance of what Schlichter said. Odd.

For me, the most interesting person present was James Delingpole. (It was while looking to see if Delingpole had said anything about this meeting himself that earlier today got me noticing this.) The mere possibility that Delingpole might now dig into what Schlichter, and all the other Austrianists before him, have been saying about money and banking was enough to make me highly delighted to see him there, insofar as anything about this deeply scary story can be said to be delightful. But it got better. I introduced myself to Delingpole afterwards, and he immediately told me that he considered this the biggest story now happening in the world. So, following his book and before that his blogging about red greenery, Delingpole’s next Big Thing may well prove to be world-wide monetary melt-down. I would love to read a money book by Delingpole as good and as accessible as Watermelons. If Delingpole’s red greenery stuff is anything to go by, the consequences in terms of public understanding and public debate of him becoming a money blogger and a money book writer could be considerable. So, no pressure Mr D, but I do hope you will at least consider such a project.

Do you think that the people occupying Wall Street are all idiots, parasitical permanent students, studying nothing of value, and demanding everything in exchange for that nothing? See also the previous posting, and its reference to “the zombie youth of the Big Sloth movement”.

Maybe most of the occupiers are like that, but this guy seems to have grabbed the chance to say something much more sensible. Fractional reserve banking (evils of). Gold standard (superiority of). Bale-outs (wickedness of). Watch and enjoy.

What a laugh (in addition to being profoundly good) it would be if the biggest winners from these stupid demos were Ron Paul, and the Austrian Theory of Money and Banking.

I submitted a comment to this blog, “From Poverty To Power”, by Duncan Green, who is involved with the Oxfam International website. Oxfam International, I should point out, is a highly political non-government organisation that promotes what seems to be a distinctly anti-trade, anti-capitalist agenda. He supports the idea of a tax on global financial transactions, that has sometimes been dubbed a “Robin Hood tax” (rob the rich and give to the poor, geddit?). Samizdata readers will know the blogger, Tim Worstall, well, who leaves a typically well-argued comment on the piece I link to. I decided to have a pop myself. I have no idea if my comment made it on (I used a different ID). Here it is:

“I love the way that some here dismiss Tim. For those who don’t know, he is an entrepreneur and I suspect, knows more about economics and business than most of the folk on this board. His point seems to be unanswerable: taxes are a cost. Indeed, that is often their point.”

“For instance, we tax alcohol and tobacco, for example, to drive down consumption for health reasons. Policymakers support imposing tax “costs” on certain items of consumption to reduce turnover. Sometimes, it is argued by people that property should be taxed more to discourage speculation in property, etc.”

“So it seems fairly clear that taxing financial transactions will mean there will be fewer transactions overall, and that the volume will decline. This will, as Tim Worstall states, reduce liquidity, widen the bid-offer spreads in financial markets for things such as currencies, bonds, equities, commodities and so on. It will therefore be more expensive for people to obtain mortgages, buy currencies when on holiday, and so on. Of course, the tax will affect groups differently – that is another issue. But there will be considerable knock-on effects.”

“Alan Doran: It is no doubt true that some funds will migrate to “rogue” tax havens where FTT does not hold sway. Well, a less negative way of putting it is that people do business where it is cheaper to do so, ie, where there are lower taxes. That is what is meant by economic freedom.”

“An example of this is when, in the very late 60s, a change to the US tax treatment of bonds encouraged the development of an offshore eurodollar market in London. Capital migrates. If people want to stop or cut financial transactions and prevent trade, they should be more honest about it.”

The idea of a financial transaction tax, or “Tobin Tax” (named after the economist, James Tobin) has been knocking around for some time. The Economist had a good item on it back in 2001.

Separately, Oxfam’s socialist tilt has been noted for a long time.

Yes, on Tuesday 11th, at around teatime, at the House of Commons, Steve Baker MP, Tim Evans and Detlev Schlichter (the links because both of the gents in the bold and blue lettering have had recent (favourable) mentions here) will be asking: Is the global economy heading for monetary breakdown?

I’m guessing the answer is going to be: yes. Although, I’m already imagining a comedy sketch where the first two say, actually, we’ve changed our minds, the answer is no. The world’s currencies are all absolutely in the pink. Quantitative Easing is working a treat. We can all relax. And Speaker number three finds himself forced to agree with the first two. “Guys, you’re right. My book is rubbish.” If only.

Please spread the word about this event, not just so that people in the London area who are able to attend it may be persuaded to do that, but so that people all over the world may learn that ideas of monetary sanity are being argued for inside the House of Commons.

“The boost to growth from more monetary easing and more deficit spending – naturally always transitory and the source of further misallocation of resources – will be ever more faint and short-lived. Instead of igniting a new false boom, a progressively larger share of the policy stimulus will simply evaporate in the service of maintaining the accumulated misallocations, of avoiding a correction of artificially raised asset prices and of bloated balance sheets. As the manufactured recoveries get weaker, fiscal deficits get larger as a result of the combination of ongoing welfare state outlays and futile Keynesian stimulus spending.”

(204-205)

“Given the theoretical analysis in this book and the consistently devastating historical record of state paper money, it is remarkable that those who advocate commodity money today are either marginalised as slightly eccentric or made to extensively explain their strange and atavistic-sounding proposals while the public readily accepts a system of book entry money in which the state can create money without limit. The global financial crisis that commenced in 2007 is a case in point. The crisis constitutes a thorough and illustrative indictment of the alliance of state and financial industry, of a system of expanding state paper money and government-supported fractional reserve banking. Yet, the political class and the media managed to put the blame on capitalism and on greedy bankers.”

Paper Money Collapse, page 243, by Detlev Schlichter. I single out these quotes for touching on two key issues: the declining effectiveness of Keynesian stimulus spending – assuming it was ever valid in the first place – and the fact that the public, aided by the political classes, have, with some exceptions, managed to completely misunderstand our present crisis.

This book is not comforting reading, nor is it always easy to read. You have to concentrate. But it is a “must-read”. For me, one of the most valuable insights of this book is how it explains how the general price level in an economy can appear to be stable but that injections of fiat money into the system can derange relative prices for consumption, intermediate and production goods. This point is vital. It explains why those central banks, such as the Bank of England, got dangerously complacent in the 90s and noughties when the inflation targets they had been set appeared to behave. But all the while, the surges in money supply growth created a bloated financial sector and property market bubble.

He also rebuts the argument, sometimes used by opponents of commodity, or “inelastic” money, that a growing economy needs a growing supply of money to ensure stability. Untrue. At most, an expanding economy, with growing innovation, division of labour and productivity growth, should see a mild deflation over time (which is good for people who want to save by holding cash). But as Schlichter explains, there is no reason in logic or evidence why a mild price deflation should hamper economic progress once people get used to the idea that their money will buy a rising stock of goods and services through time. He uses the analogy of computers. In recent times, the hourly wages needed to buy, say, a mobile phone have slumped. Has that stopped people from going out and buying these devices? Of course not.

Schlichter’s explanation of how fractional supply banking works is crystal clear and, in my view, he explains it slightly better than say, Murray Rothbard did in his The Mystery of Banking, although the latter book is still well worth reading. And Schlichter’s style is more sober and less brash in its tone than the approach adopted by Thomas E Woods in his book about the crash, although Woods’ explanation of Austrian business cycle theory is pretty good.

All these books are useful for driving home key points about how we have arrived in our current pass. Schlichter, precisely because he used to work in the investment management business for so long, speaks not as an ivory tower academic, but as someone who has been on the practical side of finance. He knows that much of what appears to be “free market banking” is anything but; in fact, as he describes it, much of what now goes on in Wall Street, the City or wherever is a hybrid of market and state planning. In its way, it is profoundly corrupt. Schlichter also mentions how such a large chunk of the economics profession is locked into the philosophy that drives the current system – without it, many of these people would have to do something else for a living.

Perhaps the scariest part of his book is when Schlichter points out that the derangement of the capital system in the West is worse than in the late 1970s, when the-then Fed chairman, Paul Volcker, pushed up interest rates to record highs to purge some of the malinvestment and rottenness from the system. The cigar-chomping Volcker was a brave man, and he had the support of the-then presidents Carter and Reagan (Carter sometimes needs more credit than he gets). I cannot see any such central banker now receiving such support for this sort of thing. Instead, we’ve got ourselves “Helicopter Ben”.

Paper Money Collapse is one of the best books to come out of the financial crisis, maybe the best so far.

Peter Thiel, the founding CEO of PayPal, has an essay up that makes the contention that the pace of technological innovation in the West, for various reasons, has slowed. He argues that this paradoxically may explain why, in the absence of serious tech change, investors are instead drawn to the dangerous finangling of asset markets such as property, and have fallen prey to the easy charms of high leverage. It is quite an interesting idea.

Here is an interesting couple of paragraphs:

“The most common name for a misplaced emphasis on macroeconomic policy is “Keynesianism.” Despite his brilliance, John Maynard Keynes was always a bit of a fraud, and there is always a bit of clever trickery in massive fiscal stimulus and the related printing of paper money. But we must acknowledge that this fraud strangely seemed to work for many decades. (The great scientific and technological tailwind of the 20th century powered many economically delusional ideas.) Even during the Great Depression of the 1930s, innovation expanded new and emerging fields as divergent as radio, movies, aeronautics, household appliances, polymer chemistry, and secondary oil recovery. In spite of their many mistakes, the New Dealers pushed technological innovation very hard.”

“The New Deal deficits, however misguided, were easily repaid by the growth of subsequent decades. During the Great Recession of the 2010s, by contrast, our policy leaders narrowly debate fiscal and monetary questions with much greater erudition, but have adopted a cargo-cult mentality with respect to the question of future innovation. As the years pass and the cargo fails to arrive, we eventually may doubt whether it will ever return. The age of monetary bubbles naturally ends in real austerity.”

It does rather go against the ideas of Matt Ridley about whom Brian Micklethwait writes below on this blog. Ridley’s take on the pace of events is far more optimistic: he does not, for instance, share the gloomy outlook on food production that Thiel makes.

This rather gloomy “are the easy economic gains gone for good?” theme was also made recently in the Tyler Cowen book, called The Great Stagnation. Here is a somewhat critical review by Brink Lindsey.

Dale Halling, an entrepreneur and scourge of things such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and anti-patent campaigners, has his own take on why the pace of innovation in the US may have slowed.

I can see why a certain gloom might set in. Many of the innovations we see today, especially in things such as consumer electronics and mobile phones, don’t have the majestic appeal of a space rocket, tall building or breakthrough in medicine. But these things are continuing: materials science, for example, which is an area that is not very “sexy” (to use one of my least favourite epithets) is full of innovation. And there are the developments in biotech and nanotechnology, to take other cases. And let’s not forget that even in the midst of the Industrial Revolution, some people claimed that all that could be invented had been.

And here is another example of the sort of concern that gets aired about where all the big inventions have gone, taken from The Money Illusion blog:

“My grandmother died at age 79 on the very week they landed on the moon. I believe that when she was young she lived in a small town or farm in Wisconsin. There was probably no indoor plumbing, car, home appliances, TV, radio, electric lights, telephone, etc. Her life saw more change than any other generation in world history, before or since. I’m already almost 55, and by comparison have seen only trivial changes during my life. That’s not to say I haven’t seen significant changes, but relative to my grandma, my life has been fairly static. Even when I was a small boy we had a car, indoor plumbing, appliances, telephone, TV, modern medicine, and occasional trips in airplanes.”

The worry is, of course, that in a world of low innovation and weak genuine economic growth, political fighting over the economic pie becomes nastier, and certain groups find life becomes very uncomfortable. Not a happy thought.

Johnathan Pearce regularly mentions here the Rational Optimist himself, Matt Ridley, very admiringly, most recently in this posting. For those who share JP’s admiration, there’s a video of his recent Hayek Lecture, which everyone who wins the Manhattan Institute’s Hayek Prize, for the year’s best book promoting the ideas of individual liberty, gets to give.

Videos are also very handy for people like me, who only learn things half decently if told them several times, in different media, in different voices, so to speak.

I’m now watching this video at Bishop Hill, to whom thanks because this is where I learned of it.

Here’s a quote from the lecture (of the SQotD sort that we like here) that has already stood out, as I concoct this little posting:

Self-sufficiency is another word for poverty.

Maybe that’s two words. But: indeed.

As the man introducing him said, one of the things that makes Ridley particularly special as a writer is the enormous range of evidence that he brings to bear on the matter of why trade and trade networks work so fabulously well, compared to isolated individuals or isolated local communities.

The lecture lasts nearly an hour, but shows every sign so far of being very well worth it.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|