We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Paul Mason, BBC Newsnight’s economics editor (and the guy who fronted that Keynes v Hayek radio show we’ve blogged about here), picks Detlev Schlichter’s Paper Money Collapse as one of his five economics books to give people for Christmas.

Mason begins his Guardian piece thus:

Two questions predominate in this year’s slew of books on economics. The first is the most obvious: how do we get out of this mess? It’s a question that has set authors along many roads but they all lead to the same destination: a bigger role for the state and the need for renewed international co-operation.

Which, alas, explains why Detlev Schlichter is so pessimistic about good sense prevailing in financial policy before ruin engulfs us all. The world’s rulers have pushed the world slowly but surely into a huge hole, and all that Mason’s authors (aside from Schlichter) can recommend is digging the hole ever deeper.

A “bigger role for the state” is not the solution to the world’s problems just now. That is the problem, and it has been for many decades.

At least Schlichter’s kind of thinking is getting around, and, as this piece by Mason proves, in some somewhat surprising places. Mason may not fully understand Austrian economics to the point of actually agreeing with it, but he does seem (as I said towards the end of this earlier posting) to respect it. He knows it is saying something important.

Schlichter has been unwavering in his pessimism about the world getting “out of this mess” and he is being proved more right with every week that passes. When total ruin does arrive, we can only hope that he and people with similar opinions to his will then be listened to rather more.

Reading this piece, linked to by Instapundit today, we see that politics in the USA, and in fact everywhere, is a trialogue rather than a dialogue. All parties to the trialogue (definitely including me) believe that the other two camps are wrong, and many in each camp believe that the other two camps are actually one camp.

The three camps are:

Camp 1: Capitalism is fine, so long as the government stays in charge of it and does a few more of the right things and a few less of the wrong things. The mixed economy is fine, if only we can just mix it right, and meanwhile preserve confidence that all will be well. No need for radical change. Trust us. No, we’re not convinced that’ll work either. Camp 1 is very powerful, very clever, very unwise. For now.

Camp 2: Capitalism is an evil mess. This crisis was caused by capitalism – naked, unregulated, unrestrained – being let loose by neo-liberal fanatics. What should be a poodle has become a wolf. Do whatever it takes to make capitalism a poodle again. Yeah, yeah, we need a bit of capitalism, to make stuff, but not nearly as much as we’ve been having lately. Anyone who gets in the way … boo! We hate you! No, we don’t think that’ll really work either, even if the people were willing to give it a go. They won’t, so boo! And if they did, it would fail horribly, and we’d have to blame capitalism even more. So … boooooo. Camp 2 is very stupid, but horribly numerous.

Camp 3: Capitalism would be great, but what we’ve had has not been capitalism – unregulated, unrestrained, as hoped for by us neo-liberal fanatics – but capitalism mixed with statism in a truly horrible way. What we’ve seen in the last few decades has been crony capitalism, capitalism with politicians in its pocket, so that whenever a big chunk of capitalism looks like failing, most notably a big bank, the politicians squirt more money at it. Which ain’t proper capitalism. Meanwhile, capitalism even of the crony sort makes better stuff. Capitalism, the real thing, should also be allowed to make better money, the kind that is allowed to fail if it does fail. The adjustment process will be horrific. No, we’re not sure that will work either. If we could do it, it would work great. But will we ever be allowed to do it? Camp 3 is right. But maybe not numerous enough or clever enough (maybe not wise enough) to win, and prove itself right. → Continue reading: The three way argument

People who know me are most likely sick of my ranting against the Economist magazine, but an article in the present edition deserves to be noted – as example of establishment statist folly.

Under the title of “Poor By Definition” we are told that the Chinese government has adopted an international measure of poverty (support for international government, European-world-whatever, is one of the defining features of the establishment to which Economist magazine writers belong) which will mean that one hundred million extra people will get various forms of government benefit. This is “good news” – “for them” and “for the economy”.

Let us leave the World Government (world definition of poverty, claim of entitlement…) stuff aside – like its support for the European Union, the international statism of the Economist is too demented (and too unpopular – outside a narrow international elite) to be worth further comment. I will just comment upon the social and economic claim being made in the article.

One hundred million MORE (not less) people getting various forms of government benefit is a “good thing”. Someone can only suppose it is “good for them” if they have ignored all the careful examination of what welfare dependence does, to individuals, families and whole communities. Works such as “Losing Ground” have been out for some time – but if the Economist magazine writers have not yet got up to speed with Aristotle and Cicero (who made similar points about the Greek and Roman worlds) it is perhaps too much to hope they would have read and understood more recent studies on how just handing out benefits undermines people – destroys families, undermines communities by destroying self help and mutual aid. And on and on – the growth of the “underclass” and the destruction of such institutions as the family among large segments of the population (the poor) all over the Western world, has been a central element of the history over the last 40 to 50 years – but the Economist magazine writers have totally missed it.

As for “good for the economy” this is the spend-our-way-to-prosperity fallacy that the Classical Economists (such as J.B. Say and Bastiat) thought they had killed off – but got a zombie rebirth with the influence of the late Lord Keynes. As Hunter Lewis points out in his “Where Keynes Went Wrong“, what we call “Keynesianism” (all the central fallacies) had been refuted long before Keynes was even born – even Karl Marx (not known as a hard core “right winger”) laughed at the absurdities of what is now called “fiscal and monetary stimulus”. However, neither the works of the Classical Economists or more recent works (such as those by W.H. Hutt.., Henry Hazlitt, Ludwig Von Mises and many others) have had any effects on the minds of the international elite – because they have never read such writers. Their education is confined to nonsense and, being intelligent (but not wise) and hard working people, they absorb the nonsense and it remains with them for the rest of their lives. They base all their policy opinions and proposals on a foundation of nonsense – which they learned (with great attention) in their early years. They are (falsely) taught that rejecting common sense is the mark of the “intellectual” (putting them above the common herd of humanity) – and so they reject common sense (basic human reason) with a passion, embracing the absurdities they are taught, perhaps, because what they are taught is absurd.

Lastly the Economist magazine article declares that the money is better spent on expanding welfare schemes than on Chinese banks. An odd statement considering that the Economist magazine has been the leading defender, in the English speaking world, of credit bubble banking and government bailouts. From the rather limited interventionism (corporate welfare) suggested by Walter Bagehot (third editor of the Economist and enemy of then Governor of the Bank of England who, quite rightly, thought that Bagehot’s suggestions would encourage all that was bad in banking) to the “unlimited” (their word – used repeatedly in articles) money creation (money creation from NOTHING) that the Economist magazine has supported in relation to bank bailouts in the United States and for bank, and national government, bailouts in the European Union. Again for the Economist magazine to attack money being thrown at the banks (anywhere) is very odd. The last demented spit of a demented article – the product of an intellectually bankrupt elite who are pushing the world towards bankruptcy. Not just economic bankruptcy – but social, cultural and moral bankruptcy also.

Paul Krugman:

“Although Europe’s leaders continue to insist that the problem is too much spending in debtor nations, the real problem is too little spending in Europe as a whole.”

Let us fisk this:

“The story so far: In the years leading up to the 2008 crisis, Europe, like America, had a runaway banking system and a rapid buildup of debt. In Europe’s case, however, much of the lending was across borders, as funds from Germany flowed into southern Europe. This lending was perceived as low risk. Hey, the recipients were all on the euro, so what could go wrong?”

Nice piece of snark, which I do not demur from.

“For the most part, by the way, this lending went to the private sector, not to governments. Only Greece ran large budget deficits during the good years; Spain actually had a surplus on the eve of the crisis.”

That may be true. I have not checked. However, the fact that Spain’s public finances went down the toilet so fast does not quite suggest that the Spanish public sector was a model of mean-minded prudence.

“Then the bubble burst. Private spending in the debtor nations fell sharply. And the question European leaders should have been asking was how to keep those spending cuts from causing a Europe-wide downturn.”

No, they should have been facing up to the fact that a vast number of mal-investments were caused by a decade of under-priced credit, and that there was no way that such a build-up of bad investments can be unwound painlessly. Seeking to hold off the pain by increasing public spending (and hence scaring the hell out of the global bond market) is hardly likely to achieve the desired effect.

“During the years of easy money, wages and prices in southern Europe rose substantially faster than in northern Europe. This divergence now needs to be reversed, either through falling prices in the south or through rising prices in the north. And it matters which: If southern Europe is forced to deflate its way to competitiveness, it will both pay a heavy price in employment and worsen its debt problems. The chances of success would be much greater if the gap were closed via rising prices in the north.”

That may be true in crudely political terms; after having enjoyed the fat years, those who have done so are not likely to enjoy a lean period. However…

“But to close the gap through rising prices in the north, policy makers would have to accept temporarily higher inflation for the euro area as a whole. And they’ve made it clear that they won’t. Last April, in fact, the European Central Bank began raising interest rates, even though it was obvious to most observers that underlying inflation was, if anything, too low.”

Well, it seems a bit glib to assume, as Keynesians like Professor Krugman do, that the inflation will prove to be temporary… Riiiight… One key problem for the eurozone, as he ought to know, is that labour markets in much of the region are so heavily regulated that getting a meaningful adjustment in wages and prices is hard, and yet this has to happen if countries such as Greece and Germany are to co-exist under the same currency area without strife. The same issue, of course, would apply if the whole region were to adopt, say, an inelastic system of real money instead of fiat money issued by a central bank or banks.

Another point for Professor Krugman to remember is that in some member nations, such as France, there has been double-digit percent unemployment for the young long before anyone had heard about sub-prime or credit crunches. And Europe’s record for wealth and job creation, compared to that of the US prior to the crunch, has been and remains lamentable.

James Taranto quotes Thomas Edsall, saying (among other things) this, about the kinds of votes that Democrats are now trying to get, and other votes that they are no longer bothering to try to get:

All pretense of trying to win a majority of the white working class has been effectively jettisoned in favor of cementing a center-left coalition made up, on the one hand, of voters who have gotten ahead on the basis of educational attainment – professors, artists, designers, editors, human resources managers, lawyers, librarians, social workers, teachers and therapists –

Edsall goes on to say that the whereas the Dems have now given up on the white workers, they are still eager to get all the non-white workers to vote for them.

One of the ways to understand the libertarian movement, it seems to me, is that it is an attempt to convert from their present foolishness all those “professors, artists, designers, editors, human resources managers, lawyers, librarians, social workers, teachers and therapists” whom Edsall so takes for granted. It gives them the “social libertarianism” that they are so wedded to (even if they often don’t get what this actually means), but it insists on the necessity of at least some – and in the current circumstances of economic crisis – a lot more – libertarianism in economic matters. Okay, libertarianism will never conquer these groups completely, but it threatens to at least divide them, into quite a few libertarians or libertarian-inclined folks and not quite so many idiots.

Also, demography is not destiny, when it comes to voting. People’s “interests” are not necessarily what many party political strategists assume them to be.

The thing is, it is entirely rational to vote for more government jobs and more government hand-outs (a) if you are at the front of the queue for such things, and (b) if the supply of such things is potentially abundant, or not, depending on how you and everyone else votes. But, if the world changes, and you find yourself at the top of the list to have your job or your hand-outs taken away from you, in a world which is going to take these things away from a lot of people no matter how anybody votes, it makes sense to ask yourself different questions, and to consider voting for entirely different things. Like: lots of government cuts, so that you aren’t the only one who suffers them, and so that the economy has a chance of getting back into shape in the future, soon enough for you to enjoy it.

The far side of the Laffer Curve is a rather strange place. Different rules apply.

Quite a lot of unemployed British people voted for Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, because they reckoned that Thatcher was a better bet to create the kind of country that might give them – and their children and their grandchildren – jobs in the future and a better life generally. (Whether or not they were right to vote for Thatcher is a different argument. My point is, this is what they did, and they were not being irrational.)

There is also the fact that how you vote in such circumstances of national and global crisis will be influenced, far more than in kinder and gentler times, by how you think. For a start, how bad do you think that the national or global crisis actually is? If you think it’s bad, what policies do you think will get that economy back motoring again, in a way which has a decent chance of lasting? How you vote depends on how you think the world works. And how you think can change.

The concept of property is fundamental to our society, probably to any workable society. Operationally, it is understood by every child above the age of three. Intellectually, it is understood by almost no one.

Consider the slogan “property rights vs. human rights.” Its rhetorical force comes from the implication that property rights are the rights of property and human rights the rights of humans; humans are more important than property (chairs, tables, and the like); consequently, human rights take precedence over property rights.

But property rights are not the rights of property; they are the rights of humans with regard to property.

– from The Machinery of Freedom (1973) by David Friedman, Part 1, “In defense of property”.

This is an attempt to get an Instalanche, so he will probably ignore it just to make the point that he doesn’t do Instalanches for anything that flat out asks for it. Although, on the other hand …

Either way, two recent objects of linkage at Instapundit in recent times have been Climategate and Goldman Sachs. Well, this Climategate email, spotted by Bishop Hill commenter “GS” (3:27pm), concerns Goldman Sachs, so the Prof ought at least to be interested:

Goldman Sachs #4092

date: Mon, 18 May 1998 10:00:38 +0100

from: Trevor Davies

subject: goldman-sachs

to: REDACTED,REDACTED,REDACTED

Jean,

We (Mike H) have done a modest amount of work on degree-days for G-S. They now want to extend this. They are involved in dealing in the developing

energy futures market.

G-S is the sort of company that we might be looking for a ‘strategic alliance’ with. I suggest the four of us meet with ?? (forgotten his name) for an hour on the afternoon of Friday 12 June (best guess for Phil & Jean – he needs a date from us). Thanks.

Trevor

Instapundit has also long been interested by the BBC, as a phenomenon of more than local interest. So I would also recommend to him, and to people generally, a read through of the Bishop Hill comment two down from that one above, this time from “ThinkingScientist” (3:41pm). He copies and pastes an email from a BBC Producer to Keith Briffa, about how Briffa must “prove” (the BBC Producer’s inverted commas) in a BBC TV show that there is something very extreme about the supposed current warming spurt. In other words, Briffa must put the C (for catastrophic) in CAGW.

GW for global warming has clearly been happening, although it is not nearly so clear that it is still happening now. (Anyone who denies the second is routinely accused of denying the first.) A for anthropogenic GW is widely believed in, but its scale and even existence are matters of fierce controversy. It’s that C for catastrophic on the front of AGW that this is all about. For a power grab this big, there has to be a C in there.

LATER: And, we have our Instalanche. Many thanks sir. (And thanks to the commenter who corrected my earlier wrong spelling of Instalanche.)

Last Tuesday Detlev Schlichter gave another talk, one of several that he is doing around now in various parts of the world, on Paper Money Collapse. Last Tuesday’s talk was organised by the Adam Smith Institute. I attended this talk and can vouch for the fact that the audience was such that it was standing room only by the time it started, partly thanks (or so I was told the following day) to this City AM report of an interview that they recently did with Schlichter.

This talk is now available for viewing on video, a fact which I learned at Libertarian Home, thanks to a posting there by Andy Janes, who describes it as having been “very impressive, if terrifying”. Indeed. You can watch it there. It lasts just under fifty minutes.

The Daily Telegraph has an article defending the idea that general practitioners can and sometimes do out-earn the banking business. Of course, people have not traditionally gone into the medical field looking to make millions, although some innovators of medical patents, for instance, may have done just that. Generally speaking, I take the view that so long as doctors are operating in a free market, then what they receive is a matter of indifference to me. Good luck to those who do well, I say. If we had a genuine market in healthcare, then the high salaries paid to the best doctors would, in time, attract bright people to become doctors rather than say, derivatives traders, or whatever.

Of course, this is not the present situation. With many doctors, their pay is partly driven by their membership of a restricted profession and in the case of the UK, by the money spent by the taxpayer. And as for bankers, or at least some of them, they too benefit from the privileged access to central banking funding of their employers, from bailouts, from barriers to entry erected by regulators, and so on. So if people in Wall Street and the City do get sniffy about how much the men and women in white coats sometimes get paid, remember, they are not quite operating in a free market world, either.

Yes, I know that there might be some room for doubt here, but an example I came across in the news pages of CityAM today clearly highlights how so-called environmental taxes are hurting the economy and costing jobs, often in areas already in dire straits:

RIO TINTO yesterday said new environmental taxes and red tape were partly to blame for the closure of its Lynemouth aluminium smelter in Northumberland, risking 600 jobs.

The mining giant said the smelter “is no longer a sustainable business because its energy costs are increasing significantly, due largely to emerging legislation.

It is thought that the coalition’s controversial plans for a carbon price floor, announced in the 2011 Budget, are being blamed alongside EU emissions trading and large combustible plant rules.

Earlier this month, the lobby group Energy Intensive Users Group said Rio Tinto was among dozens of firms asking the government for some relief from the carbon price rules.

An agreement has not been made in time for Lynemouth to remain open, though a government “support package” is due before the end of the year.

The government recognises the need to support energy-intensive industry,” said a Treasury spokesperson yesterday.

Personally, I think risking 600 jobs is pathetic. If the AGW alarmists are really that good, they should be looking to risk millions. They need to raise their game.

Sorry for the sarcasm, but you can see why this blog, along with others, gets angry about the lying and bad faith of those “scientists” who exaggerate their doomongering, and the politicians who embrace their ideas. It has consequences for actual lives.

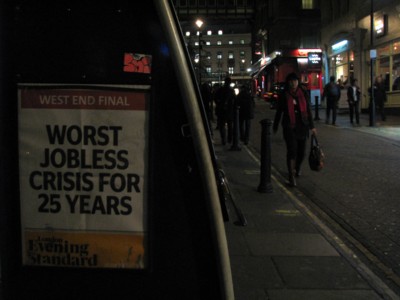

This evening I dined with a friend, and on my way there took this snap of an Evening Standard headline. A couple of years ago I thought that the Evening Standard itself – never mind these billboards – would soon be extinct. But although diminished in number, these headlines are still a familiar part of the London scene, now as then usually telling of catastrophe of one kind or another, public or personal. This evening’s offering was no exception:

Here‘s the story. Depending on your preferred explanation for this sad circumstance, you’ll pick out a different bit of the story. I pick this:

The shocking new total was published today as Bank of England governor Sir Mervyn King warned Britain is in danger of sliding back into recession.

He downgraded his growth forecasts again, saying the economy will expand by one per cent this year and next, a fraction of the hoped-for rate.

As Instpundit would say: Unexpectedly! It would appear that quantitative easing is proving less than completely stimulating. We here are not shocked by this bad unemployment news.

For a little light relief, here’s a snap I took later, on my way home:

The advertising trade was bound to take advantage sooner or later of the wave of health and safety signage that is such a feature of British life just now. This is the first time I’ve noticed it, but I’m sure others have seen such things many times already.

In London right now, it is an hour or more past 9 am. But in Cape Town, South Africa, just over an hour ago, it was 11:11 am, on the 11/11/11 (November 11th 2011), and South Africa needed 111 runs to win the international cricket match that they were playing against Australia. South Africa, sadly, were not 111-1, chasing 222. They were 126-1, chasing 236. So, time and date oddities aside, a cricket match is drawing to a calm, even predictable end. Right? Well, yes. But yesterday, 10/11/11 or 11/10/11 or whatever you call yesterday, it was very different.

Those baffled and/or repulsed by cricket and its arithmetically obsessed followers like me should probably skip the next few paragraphs. Summary: this has been one weird test match. But now, skip down to where it says: “Okay, here is my serious Samizdata-type point.”

Okay cricket nutters, on we go with the story. Here is the sort of thing that was happening in Cape Town yesterday:

W W . 4 . . | W . . . . . | . . W . . . | . . . 4 . W | 1 1 . W

At the end of the first day of this test match, Australia had reached a rather meagre 214-8, but on the morning of the second day, yesterday, they did better, getting to 284 all out, thanks to more excellent batting by their new captain, Michael Clarke, who was last out for 151. South Africa then progressed to 49-1 at lunch. So far so normal.

About an hour later South Africa were all out for 96 having only just avoided the follow-on, the above WW stuff being a slice of that action. Australia then went into bat, and at the tea interval were themselves struggling on 13-3. Then, in no time at all after tea, they had slumped to a truly catastrophic 21-9. They then recovered, if that’s the right word, to the dizzy heights of 47 all out. Another action slice:

W . . 3 . . | . . . W . . | . W . W

The South African Vernon Philander, playing in his first test, took five wickets for fifteen runs, bringing his total for the match to eight. Quite a start. Earlier Shane Watson had taken five for seventeen for Australia.

A Cricinfo commenter suggested that Australia should declare at tea time, setting South Africa two hundred to win in very adverse conditions. He didn’t say, an hour later, that Australia should have declared at tea time. He said it at tea time, when Australia were 13-3. And they probably should have! Australia having batted successfully in the morning, South Africa began their second innings and ended this bizarre day with similar batting success, reaching 81-1 by the close. Today, they began needing only a further 155 to win. If South Africa do win, they’ll be thanking their last wicket pair, Dale Steyn and Imran Tahir, who added thirteen and saved that follow-on. Take away that stand, and South Africa might have lost by an innings by now. As it now stands, and given that they have made a fine start this morning, South Africa now look sure to win.

If, despite being a cricketphobe, you read all that and would like to know approximately what it means, think of it as the cricketing equivalent of a world cup soccer quarter-final match between, say, Italy and Germany, where the scorecard after half and hour was 0-0, but by half time it was Italy 6 Germany 0, and then about fifteen minutes later it was Germany 8 Italy 6, followed by twenty entirely goalless minutes with Germany looking favourites to play out time and win it, 8-6. Calm, mayhem, even greater mayhem in the opposite direction, calm. Bizarre, right? I’ll say.

Okay, here is my serious Samizdata-type point. (Welcome back, normals.)

My point is that the internet is uniting the world into one huge ultra-high-density global super-city. Not a global village, because that would suggest that everyone knows what everyone else is talking about, and, as the above few paragraphs illustrate very adequately, that is not at all what is happening. Most of us are baffled by most of what goes on in our Global Super-City, most of the time. But the thing is, cricket fans like me can now tune into the fine detail of matches which we would never before have been able to find out about. And you can likewise easliy tune into the fine detail of whatever it is that gets you excited and has you interrupting your normal daily routine. → Continue reading: Cape Town cricket mayhem in real time – and a united world

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|