We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

The story of rent controls has been the same everywhere they have been tried. Until they were abandoned, rent controls in Seventies Britain led to a catastrophic fall in the number of rented properties available, and they did nothing to stop unscrupulous Rachmanite landlords. Rent controls accelerated the woeful degradation of much of New York’s housing stock, and in so far as there has been a boom in New York property, it has taken place in housing not subject to rent controls.The Swedish economist Assar Lindbeck has said that rent control is “the most effective technique presently known to destroy a city – except for bombing”; and the reason he has come to that conclusion is that experience has shown that it is an idiotic way to tackle the problem of high rents.

– Boris Johnson, Mayor of London, and newspaper columnist.

I should add that one of the things I notice about Ed Miliband, the Labour leader – and many others who share Miliband’s views – is not so much ignorance of economics, as hostility to the idea that humans act as they do. The assumption seems to be that to bring about desirable objective X, one should pass a law to ensure X happens, and if it doesn’t, then evil intent has caused it. So, if you want to raise pay, you pass a minimum wage law decreeing that employers must pay staff so much money; if you want to hold down the cost of rentals, you pass a law banning landlords from pushing up rents above that level, and so on. And the fact that landlords and employees might alter their behaviour as a result or that unemployment and crap rental housing might ensue is the fault of evil people, not the forseeable result of interfering in the market. And on housing prices, as Boris mentions, the main problem is that supply in the UK is artificially suppressed by planning laws. (It should be noted that people of all political persuasions favour these, either for aesthetic or more narrowly self interested reasons.) But to admit that is, for the Miliband mindset, unthinkable: the State cannot have caused a shortage of something, surely! It must be because bad, uncaring people have somehow failed to provide enough housing!

To put it even more simply, with the Milibands of this world, we are dealing with the mentality of a child. Now, I don’t care whether Miliband looks or sounds odd, or is a tosser who knifed his brother in the back, so to speak, although I suppose these things do matter. What, at root, terrifies me about the idea of this fuckwit taking power is that he is a fuckwit, and alas, insufficiently self aware of his fuckwittery and inability to deal with reality. Or perhaps another way of seeing this is that he is an example of a mindset that goes back to JJ Rousseau and further back: the idea that what matters is that one is sincere, one cares, rather than reflect on the actual results of what one does.

Is this not rather predictable?

HSBC will look into upping sticks and moving its headquarters out of London once the regulatory environment becomes clearer, its chairman said today.

“We are beginning to see the final shape of regulation, the final shape of structural reform and as soon as that mist lifts sufficiently we will once again start to look at where the best place for HSBC is,” Douglas Flint said.

He was speaking at an informal shareholder meeting in Hong Kong. This comes as a recent hike in the special tax levied on banks in the UK makes it increasingly costly to do business, people familiar with the situation told Reuters.

And this under an supposedly ‘conservative’ Prime Minister 😀 The Stupid Party indeed. If Labour wins, I imagine this will become a stampede as businesses bolt for the exit.

I am not familiar with Paul Lindley but an article he wrote set my alarm bells jangling:

Business is changing. The predominance of companies for which profit is everything – and everything else is nothing – is waning, and a new wave of entrepreneurs and socially-minded individuals is on the rise. If I could give one piece of advice to the next government, it would be this: don’t just do what’s best for business, also do what’s best for those people – the stakeholders – involved in business. (…) Consumers are becoming more morally aware. They have an increasing amount of data available at their fingertips – from the ingredients in the products they buy to the supply chains of companies – and they are demanding more from their favourite brands. A new type of company has arisen to meet this demand, already popular in the US and elsewhere abroad. Benefit corporations – or “B-corps” – are companies which include a positive impact on society and the environment, in addition to profit, as their legally defined goals.

Well if I could give one piece of advice to the next government, it would be this: don’t do anything for anyone, just stay the hell out of the way and let markets do what they do.

I suspect my idea of what “social responsibility” means is probably not the same as what Paul Lindley means, so I really do not want the state deciding which of those views is the official approved version. Anyone asking the state to facilitate their objectives is almost always looking to have them stick their thumb on the scale and protect someone’s business model against someone else’s business model.

As I said I am not familiar with Paul Lindley but I am parsing his remark “companies which include a positive impact on society” to mean he thinks a supermarket, garage or clothing store, simply by virtue of offering things people want to buy at prices they want to buy them at, does not constitute a “positive impact on society”… and he wants the state to have policies that ensure straightforward commercial enterprises which do not market themselves according to an approved list of other added-on “social benefits”, are made less competitive vis a vis those who do. As he is fairly vague on precisely what policies he wants I cannot be sure, but that is what I am getting from this article.

In the late 1970s, the top rate of income tax in the UK was over 80 per cent and the top one per cent of income tax payers paid just 11 per cent of the total. Rates are dramatically lower today, and the one per cent paid 27.7 per cent of the 2011/12 total. The idea you get more money out of the rich by putting the screws on runs counter to the facts.

– Marc Sidwell

The Labour Party has stirred up the usually rather complacent wealth management sector in the UK by vowing to end the so-called “non-dom” system under which a foreigner who wants to spend some time in the country can avoid paying tax on all his/her worldwide income and capitals gains so long as this money is kept outside the UK. If such a non-dom has lived in the country for seven years, they must pay an annual levy and depending on the duration, that annual levy is as high as £90,000. A study by University College, London, published in 2013, concluded that the system brought in more revenue for the UK than was being lost by the absence of such a system.

At face value, the non-dom system might look like a great deal for a person who is worth tens of billions of pounds, dollars or whatever and who “only” pays several thousands per year to live in the UK. But if such a person’s wealth has been largely generated outside the country and is kept outside it, what is unfair about this position? If Mr Stinking Rich brought those billions to the UK, he would have to pay a thudding great tax bill. Ed Miliband, leader of the Labour Party, must know that, or if he doesn’t, he is being reckless. The whole idea that a person should pay tax to the country of his/her birth regardless of having not lived there for a period – as is the case with the odious worldwide US tax regime – cuts against the idea that one should pay taxes that focus on where you actually live.

Matthew Sinclair has a good piece here on the issue.

From a point of narrow party politics, I suppose Ed Miliband and his colleagues think they are being clever at playing the class war card and hope to trap opponents by having to defend the non-dom system. I notice that whenever a weapons-grade knob such as Miliband makes such a crowd-pleasing proposal, it is seen as a “trap” and that therefore the other side are told that it isn’t wise to oppose it. But this sort of cowardice-as-a-tactic approach merely favours the bully. A braver, and ultimately better, argument is to state that it is in the UK’s interest to encourage internationally-minded investors and entrepreneurs (so long as they are not criminals and jihadi nutcases) to come to the UK and enrich themselves and everyone else. To pander to the zero-sum, dog-in-the-manger mindset of Miliband and others is also foolish.

There is also a broader point to be made here: such attacks represent, at the margins, part of a rollback of globalisation, of the free movement of capital and people, a process from which London, as a global financial centre, has been a mighty beneficiary.

Far too many people in the banking and financial markets more broadly have fought shy of voicing their concerns about the demented nature of so much “banker-bashing” and attacks on inequality recently. Consider the respect granted to Thomas Piketty’s fatally flawed claims about inequality and his call for draconian taxes on capital. It is sometimes stated – I heard such a statement recently at a gathering – that “neo-liberals” (ie, classical liberals) have “won” the argument and that we now need to move on. How complacent that is. The arguments for freedom and capitalism are being lost in the UK, or at the very least, they aren’t being made very effectively.

“America is the world’s most successful economy because it is a democracy”, sayeth Iain Martin. I am not convinced.

It is not a coincidence that the United States is such a success and a democracy. It is such a success because it is a democracy. Indeed, the American impulse is rooted in the rejection of tyranny and scepticism of excessive government power. That commitment to free competition – sometimes imperfect, often producing uneven results – is what drives innovation.

It is a point made brilliantly by Guy Sorman in his latest piece for CapX, published this week. As he says, if you want meaningful innovation, the lifeblood of technological improvement, rather than copying and refining existing technology, then you need that clash of ideas that happens in a free society in which those in charge can be kicked out or established players can be outflanked by upstarts.

But it is liberty, not democracy, that brings these things. It is constitutionally separated powers and limited government, which is to say limiting the scope for democratically impelled politics, that enables people to challenge established business models.

And those limits on what government can do are in precipitous decline in the USA (and elsewhere) regardless of ‘democracy’… and often because of it. A great many people are quite happy to vote for excessive government power and more ‘free stuff’ that other people will have to pay for.

The downside of zero inflation is that it does nothing to erode the value of debt, much of which is denominated in money terms. If your mortgage is £100,000 and the price level doubles, its real value has fallen to only £50,000. The world is still burdened with excessive debt, which is a worry for policy-makers. But a low inflation world forces them to confront this issue honestly, and not try to evade it by using the subterfuge of inflation.

– Paul Ormerod

Of course it is only a ‘downside’ if you are in debt, it is an upside if you are a saver and lender.

… and in order to fit in better with the people around you, feel the need to blast off about ten IQ points, you are in luck! Just watch this from our good chums over at the BBC. It is an experience a bit like holding a live piranha to the side of your head.

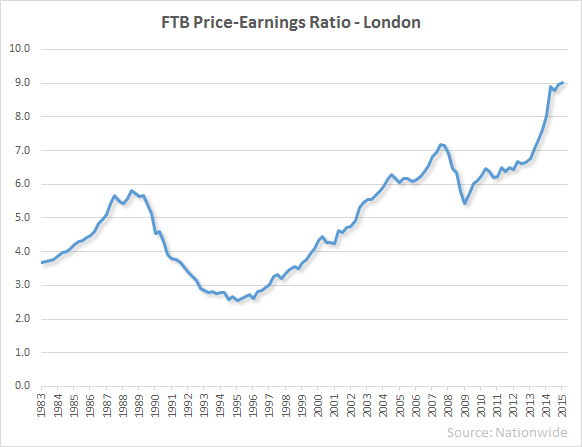

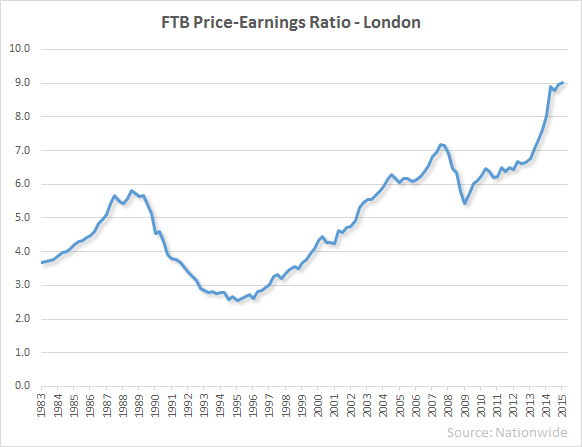

This was tweeted by Dominic Frisby earlier today:

As he says: “1st-time-buyer earnings-to-house-price ratio in London. Gulp. And London 1st-time-buyers are old too … ”

The moment interest rates go up, even slightly, there is going to be an almighty collapse.

Many socio-political forces today are about the return to tribal identity. Tribes are isolated from the Other and easily coerced through emotional appeals to identity rather than universal logic. This has picked up methinks because information and people are increasingly ignoring the borders and authority defined by the state. So the thugs among us look to draw new boundaries based on race, gender, language etc. The new tribes destined to wage continuous and pointless war.

– the pseudonymous Chip drops an absolute blinder of a comment on Samizdata. There is a reason this comment is also categorised under ‘globalization’.

Uber banned for the second time in Germany:

A regional court in Frankfurt ruled that Uber’s low-cost ride-sharing service UberPop is now banned throughout the country. The case was brought by taxi union Taxi Deutschland that been battling Uber for over a year.

And the French state agrees:

Around 30 police officers were sent into the Parisian Uber headquarters on Monday as part of an investigation into its UberPop service, which connects drivers with passengers via a smartphone app.

The state really hates it when their Permit Raj and compliant patron rent-seekers get threatened. Next thing you know, uppity consumers sick of overpriced taxies might start thinking state state involvement was not necessary!

No you don’t get to get away with that. You don’t get to advocate policies which allow you to use force to deprive people of their jobs and their opportunities and then claim that those who would have provided the jobs are the heartless ones.

You don’t get to trot out the insipid, mindless, tendentious talking points about how you are morally or intellectually superior when every “solution” you proffer is destructive and is based upon forcing others to do your bidding. You don’t get to decide whose job is worth preserving and whose isn’t and still claim the moral high ground.

You have to own this. You have to accept responsibility for the suffering your ignorance has caused and you have to understand that there is no way forward as long as you remain ignorant. Until you can begin to think rationally instead of being so full of hate that you think the best solution to every problem is to use force against those you disagree with then you can’t be accepted into the company of decent people and will always be seen as supporting those who would oppress us because that is exactly what you are doing.

– Pseudonymous commenter BenFranklin2 delivering a mighty and artful kick to the bollocks on someone else defending state imposed minimum wages, which are leading to restaurants closing in Seattle. Scroll down from main article as the link to the comment itself does not seem to work.

h/t Natalie Solent for finding this article.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|