We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

It is to do with urbanisation. Quite simply, the more people who live in cities the greater the amount of gun control.

It’s not just Britain and America. Switzerland, largely rural, has very little gun control, while America’s cities, as I understand it, tend to have plenty. I suspect one of the reasons for this is that in the cities you can have a reasonably effective police force. OK there’s the quip about “When seconds count the cops are only minutes away.” but better minutes than hours.

Also, I suspect politicians themselves are affected by this. In a city a politician finds himself surrounded by potential assassins, all of whom are nearby. “Best to disarm them”, he thinks. In less populated areas this is far less the case. It is perhaps no accident that high-rise New York City had gun control well before anywhere in the UK.

A pistol. A 1907 Dreyse to be exact.

One many significant dividing lines between, on the one hand, enthusiasts for free economies and free societies, and on the other hand those who favour a large role for the state in directing and energising society, concerns where you think art and science come from.

Those looking for an excuse to expand the role of the state tend to assume that art and science come from the thoughts and actions of an educated and powerful elite, and then flow downwards, bestowing their blessings upon the worlds of technology and entertainment, and upon the world generally. Science gives rise to new technology. Art likewise leads the way in new forms of entertainment, communication, and so on.

While channel surfing a while back, I heard Dr Sheldon Cooper, the presiding monster of the hit US sitcom The Big Bang Theory, describe engineering as the “dull younger brother” (or some such dismissive phrase) of physics. The BBT gang were trying to improve their fighting robot, and in the absence of the one true engineer in their group (Howard Wolowitz), Sheldon tries to seize the initiative. “Watch and learn” says Sheldon. Sheldon’s attitude concerning the relationship between science and technology is the dominant one these days, because it explains why the government must pay for science on the scale that it now does. Either governments fund science, or science will stop. Luckily governments do now fund science, so science proceeds, and technology trundles along in its wake. Hence modern industrial civilisation.

If the above model of how science and art work was completely wrong, it would not be so widely believed in. There is some truth to it. Science does often give rise to new technology, especially nowadays. Some artists are indeed pioneers in more than art. But how do science and art arise in the first place?

Howard Wolowitz is the only one of The Big Bang Theory gang of four who does not have a “Dr” at the front of his name. But he is the one who goes into space. He builds space toilets. He was the one who actually built the fighting robot. Dr Sheldon Cooper, though very clever about physics, is wrong about technology, and it was good to see a bunch of comedy sitcom writers acknowledging this. After “Watch and learn”, Sheldon Cooper’s next words, greeted by much studio audience mirth, are “Does anyone know how to open this toolbox?”

→ Continue reading: Some thoughts about where science and art come from (and about why governments don’t need to pay for either of them)

Sometimes, when trying to win an argument, a person might invoke the old “but it is surely just common sense that X is X or Y is Y”. And let’s face it, we all do it a lot of the time. Trouble is, this can lead us astray on difficult moral issues, for example, or in science, where “common sense” once led people of high intelligence to scoff at the notion of gravity, or that the earth was a sphere, etc. For all I know, people once thought it was “common sense” to have absolute rulers, burn witches, keep slaves and shun those of other races.

I thought about this issue when I read this item by Bryan Caplan, in discussing the Michael Huemer book that Perry Metzger recently wrote about here.

This comment in the EconLog thread, by RPLong, caught my eye:

Common sense is one of those fuzzy concepts that people invoke to buttress their arguments without providing additional facts or reasoning. I consider appeals to common sense to be a lot like saying “very, very, very…” That is, appealing to common sense provides more verbiage without providing any additional substance. It’s a waste of time. Unless we can actually show with facts and reasoning that our position is the more sensible, there is no use discussing that which appears most “commonly” to be sensible. If you have the more convincing position, then you can certainly demonstrate how much more convincing it is.

That’s surely the crux of the matter. It is one thing to say that “My opinion about the wrongness or rightness about abortion or the proper teaching of kids is just, you know, common sense.” But as soon as you start to break down the issues, look a premises, unacknowledged philosophical/other assumptions, it gets much more complicated. In some cases, an appeal to “common sense” is just an argument from authority.

“If we want a more sustainable world, achieved through and driven by popularised digital technologies, we need to reframe the conversation and make it less about depriving ourselves of the things we like.”

Liat Clark, Wired magazine.

Indeed. It is easier to persuade people of your point of view if it can be shown in a positive, life-affirming sense rather than a gloomy one. Even where I find myself agreeing with environmentalists on certain issues, I find the coercive, “let’s ban it and tax it” stance taken to be a turnoff.

If I let them compute those statistics, they’ll want to use them for planning.

– Sir John Cowperthwaite, Financial Secretary of Hong Kong from 1961 to 1971, quoted in a recent posting at the Cobden Centre blog by Sean Corrigan entitled Masterly inactivity.

According to this blog posting, these words were spoken by Cowperthwaite to, and recalled by, Milton Friedman (who had asked about the paucity of statistics), in 1963.

A regular Samizdata reader (who for fairly obvious reasons has asked to remain anonymous) submits this slightly horrifying story of what has recently happened to a friend resident in Spain. People familiar with the Spanish justice system – this is not a country where you wish to get in trouble with the law – will not find it surprising. Still, it is different, somehow, when it happens to you or someone close to you.

Occasionally one hears a story of a government overreach which makes one think that something like it could not happen in a Western Democracy, at least not on a regular basis. And if it does, it surely is due to some kind of a mistake, to which bureaucracies are so prone, or due to some corrupted government officials acting illegally. That was what I thought, after a friend who suddenly disappeared, severing all contacts with friends (although thankfully not family), reappeared after having spent four months in a Spanish jail. When this middle-aged suburban mother of young children told me that she got lucky, seeing as a maximum term for a pre-trial detention according to the Spanish law is four years, I thought that she must have misunderstood something “lawyery” – turns out, she did not (more info in Spanish here). What is worse, according to that document Spain is by no means different from several other European countries, and is not the worst among them, either.

As of now, my friend is still less than keen on discussing the legal aspects of the matter, and she has never been much interested in these things anyway. But, to paraphrase that dead revolutionary: you may not be interested in Law, but Law is interested in you. After having her apartment turned upside down and having been dragged to jail following a knock on the door, she was brought before a judge, whom she told that she just happened to have been once-friends with someone connected to something much bigger than herself or anyone she has ever known.

It took the Spanish authorities four months to corroborate her statement. In the meantime, she spent those four months in appalling conditions, with only a weekly through-the-glass visit from her husband, plus a monthly conjugal visit. No heating (in winter), filthy cells, two women sharing a cell with a toilet. Her kids still think she was away for some kind of professional training. It would have taken longer (as noted above, up to four years) if it was not for her lawyer. She made friends in jail with women who cannot afford a lawyer, and others who were extradited to Spain under the European Arrest Warrant and do not even know anyone in Spain. They are still in jail. Word is (I have not checked) that all the “Big Fish” with that big affair apparently are home free after about a month and a half in jail. The State is NOT your friend.

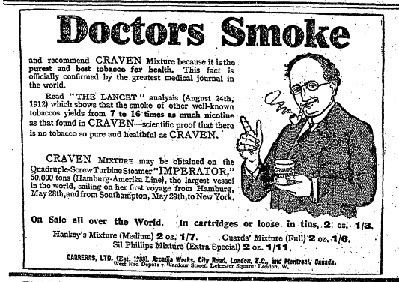

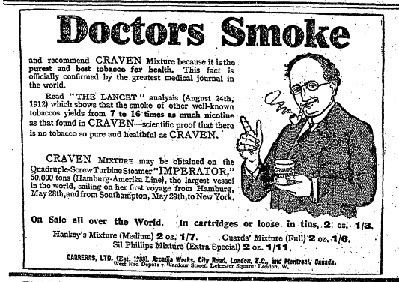

The Times, Tuesday, Feb 25, 1913; pg. 10. Click to enlarge

“We should recognize the issue of communism and Soviet espionage has become an antiquarian backwater. After all, the Cold War is over.” With these words, a typical leftish US historian, Ellen Schrecker, recommends that a whole sector of an historical era should be ignored and work on it effectively closed down. “It is time to move on,” remarks another academic, using the modern terminology that neither denies nor accepts responsibility, but leaves a mess behind for someone else to clear up. Now historians are, by definition, paddlers up backwaters, investigators of things that are “over” and move in, not move on when invited to examine data never before available. When World War Two ended historians started, not stopped, writing about it, just as an unending stream of books about Napoleon has continued in the nearly two centuries since he was bundled off to St Helena. The idea that, just as enormous quantities of material from Soviet and other archives are being released, work on them should be called off is so ludicrous that it could only have been suggested by those who feel the foundations of their beliefs and attitudes crumbling beneath their feet.

– Findlay Dunachie, reviewing a book called In Denial: Historians, Communism, and Espionage for Samizdata, in 2004. I came across that while trying to find something else, and was immediately hooked. Findlay Dunachie is sorely missed, now, still.

The good news is that, following the recent Samizdata makeover, we can now peruse the entire Samizdata Findlay Dunachie author archive.

This news item about the anatomy drawings of Leonardo da Vinci looks like a good excuse to go to Edinburgh in August:

In a series of 30 pictures, the Royal Collection Trust will show da Vinci’s distinctive anatomical drawings alongside a newly-taken MRI or CT scan. The comparison is intended to show just how accurate da Vinci was, despite his limited technology and lack of contemporary medical knowledge.

The Edinburgh Festival is mainly about the arts, rather than sciences, although in a way this exhibition transcends both. I hear mixed things about the Festival: it is, apparently, great fun but it can be a pain getting accomodation. My wife has never been to Scotland – an omission that needs to be sorted out soon.

And of course the da Vinci exhibition in this beautiful Scottish city is a reminder of the grand tradition of medicine in that part of the world.

The three main parties are all deciding how they will kill off the last vestiges of freedom of the press in Britain.

Ed Miliband was hoping to sit down with David Cameron and Nick Clegg later on Tuesday or Wednesday to agree a historic new deal which would see newspapers regulated like the BBC.

We will know soon enough exactly how they will do this, but do it they will. And you can be sure they will present it as protecting freedom of the press.

From Michael Huemer’s brief summary (right near the end of “Analytical Contents” – p. xxv) of Chapter 13 (“From Democracy to Anarchy”) Part 4 (“The Influence of Ideas”), of his newly published book The Problem of Political Authority:

The eventual arrival of anarchy is plausible due to the long-run tendency of human knowledge to progress and to the influence of ideas on the structure of society.

I originally had that up as a Samizdata quote of the day, but there already is one. Apologies for the muddle. However, I didn’t want either to scrub this posting or just leave it hanging about, so instead I am elaborating a little.

I think the word “plausible” in the above quote is apt. We can’t assume this kind of thing. But that doesn’t mean there is no reason to hope for such a thing. Why else would we be bothering?

I now have my copy of this book, and a brief glance through it suggests that there is plenty more SQotD material in it. Indeed, it seems to be the kind of book where you could pretty much pick an SQotD out with a pin.

Why don’t I try that? Let me open the book at random, and pick a paragraph at random, and see if it works as a disembodied quote. There are 365 pages in the entire book. Here is a paragraph from page 234:

But war is, putting it mildly, expensive. If a pair of agencies go to war with one another, both agencies, including the one that ultimately emerges the victor, will most likely suffer enormous damage to their property and their employees. It is highly improbable that a dispute between two clients would be worth this kind of expense. If at the same time there are other agencies in the region that have not been involved in any wars, the latter agencies will have a powerful economic advantage. In a competitive marketplace, agencies that find peaceful methods of resolving disputes will outperform those that fight unnecessary battles. Because this is easily predictable, each agency should be willing to resolve any dispute peacefully, provided that the other party is likewise willing.

Not original, but not bad. And again, plausible.

I share Michael Huemer’s optimism about the influence of (good) ideas on society. If I did not, I would occupy far less than I actually do occupy of my life arriving at and stating my own ideas, and publicising the ideas of others, such as Michael Huemer.

For the first time in recorded history, we have nearly every central bank printing money and trying to debase their currency. This has never happened before. How it’s going to work out, I don’t know. It just depends on which one goes down the most and first, and they take turns. When one says a currency is going down, the question is against what? Because they are all trying to debase themselves. It’s a peculiar time in world history.

– Jim Rogers, the investor, adventurer and commentator, as quoted at the splendid Zero Hedge website.

(I like the site’s motto: “On a long enough timeline the survival rate for everyone drops to zero.”)

On a related theme of currency debasement and government tactics, this book, Currency Wars, looks a gruesomely entertaining read.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|