This post is not going to be about “NASA screwed up, how come after 40 years we still have a space ‘program’ and not a space industry, NASA is drifting off focus and no longer has a clearly defined mission, etc.” I will leave it to someone else to write that column, because Rand Simberg (or our own Dale Amon) could do it a lot better than I could anyway.

What I do want to talk about is: how the way information is organized and presented can make a difference in how it is received – and how bureaucracy can sometimes stand in the way of effective data organization and promote cluttered thinking. When we lost the Challenger in ’86, it should have been clear that it was unsafe to launch the shuttle on that cold January morning. NASA had plenty of data to suggest that it was not prudent to launch that day – the problem is that the data was not refined into a conclusive answer, but rather was shrouded by poor communication and bureaucratic ass-covering.

Edward Tufte, professor emeritus at Yale and author of several brilliant texts on graphic design and the visual display of quantitative data, has made the Challenger accident a centerpiece of his traveling seminar. His exegesis of the Challenger disaster is available in his book Visual Explanations (Graphics Press, 2001).

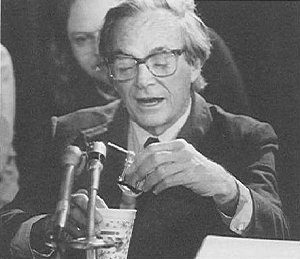

In hindsight, it was quickly determined what caused the Challenger to fail: the poor cold-weather performance of the rubber O-rings in the field joints that held sections of the solid rocket boosters together. In a memorable session of the Rogers Commission (the group that investigated the Challenger disaster) the late Richard Feynman, Nobel Prize-winning physicist, conducted a dramatic experiment. He affixed a C-clamp to a sample of O-ring material, dropped it into his glass of ice water, and then removed the clamp, revealing that the O-ring rubber lacked resiliency when cooled to 32 degrees Fahrenheit. (See photo below.) Engineers at Morton Thiokol, the Utah-based firm that made the solid rocket modules, had been concerned about the cold-weather performance of the seals, so much so that they took the unprecedented step of issuing a “no-launch warning” to NASA the day before the doomed flight. As Tufte puts it:

… the exact cause of the accident was intensely debated during the evening before the launch: will the rubber O-rings fail catastrophically tomorrow because of the cold weather? These discussions concluded at midnight with the decision to go ahead. That morning, the Challenger blew up 73 seconds after its rockets were ignited.

At this point, some would be tempted to say: “See? As usual, the engineers were right, the bureaucrats were wrong!” But the story is more complicated. Tufte argues that the Thiokol engineers failed to present a compelling “no-launch” case to NASA because (1) their analysis failed to make crystal-clear the relationship between O-ring performance and temperature, and (2) their presentation to NASA had other shortcomings, including contradictory advice in some places.

What kind of analysis/presentation might have saved the Challenger? In Visual Explanations, Tufte argues that a single graphic (had such a thing existed) could have given NASA all the data they needed to make a decision. (You can see the graphic here – it is shown on the cover of one of his booklets.)

The x- (horizontal) axis shows temperature at launch time; the y-axis shows the level of damage to the O-rings. Each dot represents a previous space shuttle launch in the years 1981-85. The forecast temperature for Cape Canaveral that infamous morning was below freezing, in the 26-29 degree range; the previous coldest shuttle launch was at 53 degrees. As Tufte points out, 29 degrees is an extreme outlier, 5.7 standard deviations outside the previous range. And, of course, the relationship of resiliency to temperature is quadratic, not linear. In other words, the Challenger mission was at substantial risk.

So the problem with the Challenger was not that the NASA bureaucrats lacked the needed data. Nor was the problem that they simply disregarded the advice of the engineers for political reasons. They had the data; what they lacked was the capacity to quickly and accurately refine the data into a clear no-launch decision.

This is the same problem that presents itself over and over in bureaucratic decision-making, especially in intelligence / antiterrorism efforts. Muhammad and Malvo’s “snipermobile,” the modified Chevy Caprice, was spotted and even apprehended at the scene of several shootings before authorities put two and two together. They received tips from thousands of disparate sources. Our intelligence agencies receive a ton of information, chatter, noise, whatever you want to call it, from sources all over the globe. The challenge for police and intelligence agencies is to refine that desultory information into a meaningful conclusion.

We know that markets do this task – refining enormous amounts of information into concise signals – exceptionally well. John Poindexter took a lot of heat for proposing a “terror futures market” in which participants could bet on events such as the Saudi government falling. Politicians, journalists and cartoonists derided the idea, but many bloggers and other commentators (such as Reason’s Ron Bailey) rose to its defense. There are limits to the applicability of markets like this, but potential benefits as well. (For example, studies have shown that weather futures markets actually outperform the US National Weather Service in predicting certain weather patterns, and you had better believe that campaign managers these days pay as much attention to political futures markets as they do to polls.)

Would something like this work for space shuttle launches? If there was a market in which we could trade, say, the probability of a failed space shuttle mission, would that have helped? Best case scenario would be: analysts independently peg relationship of temperature to risk; temperature forecasts for launch day are issued; demand for (and price of) ‘mission failure’ bets in futures market accelerates; NASA views this as a signal to postpone launch.

Building a market like that does not just happen overnight; investment bankers know the difficulties inherent in ‘making a market’. You would need a lot of knowledgeable players before the market could achieve stability and begin to provide robust answers. There’s no way to know whether a ‘shuttle futures market’ could have helped NASA in 1986, but it is hard to see how it could have hurt, either. Could the power of the free market help protect NASA’s future shuttle missions?

“I believe that has some significance for our problem.”

– Feynman’s testimony at Rogers Commission panel, Feb. 1986

Recommended Reading:

Feynman, Richard. What do YOU Care What Other People Think? Norton, 1988.

Tufte, Edward. Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative. Graphics Press, 2001.

Siems, Thomas F. 10 Myths about Financial Derivatives. Cato Institute Policy Analysis, 9/11/1997.

As I recall, Feynman gave a lot of the credit for the O-ring idea to an Air Force officer who sat next to him in the commission hearings. He had Feynman over to dinner one night and maneuvered a discussion of a clutch in his garage around to O-rings. Feynman was a little irritated at being used but seemed to understand that this had to be brought up by an outsider for political reasons.

I always had thought that the political reasons were part of the CYA operation that followed the Challenger disaster. Your column raises the possibility that they were there all along, part of a misguided CAN-DO attitude. Perhaps the graphic was never made because the insiders -as opposed to the Thiokol people- had trained themselves to not see things in unapproved ways.

I have to add that this is rank speculation on my part. I have little personal knowledge of the attitudes of NASA people back then.

I do think the terrorism futures was indeed one of Poindexter’s good ideas. His panopticon is definitely one of the worse ones.

As to attitudes of NASA people back then… there is always a pressure to get the bird off on time. Congress will damn you if you don’t perform and of course damn’s you twice as hard if you blow it up. Recently retired Sen Hollings, (the Democrat from Disney as we called him) tried to make political points over the dead bodies of the astronauts. This happened after Apollo as well, although it was even uglier and Harrison Storm (I think that is the right name) of North American Aviation was thrown to the lions to save the program.

There does not seem to have been anywhere near the level political pornography over Columbia that occured with the other two losses.

And let’s face it. There have been only 21 deaths in spacecraft in 44 years so even the government has not done all that badly in terms of frontier safety.

Where they have fallen down is that we have been parked in LEO for 30 years…

Had we gone pure private sector there would have been a higher death toll over a much larger number of flights in much cheaper vehicles and it would hardly have made the news unless it was particularly spectacular.

It’s only a matter of time before we start losing people at the rate of aviation in 1903-1910. We’re only months if not weeks away from ‘the Wright Brothers’ event in space.

Problem with a mission failure market: you correctly predict a failure, then NASA aborts, and you lose your bet. So, what incentive to predict correctly?

There’s a lot more to the story of the ice water experiment than I was able to cram into a single blog post. Feynman’s book “What Do YOU Care What Other People Think?” (which was actually released posthumously) has the whole background on the story … the General that Mr Collins refers to was Gen. Donald Kutyna.

Another thing I would have pointed out (but for the fact that the entry was already approaching blogopotamus status) is that Feynman’s live “experiment”, though dramatic, was also flawed as a piece of pure science, because there was no “control” piece to compare it to. Did the rubber lose resiliency because it was cold, or because it was wet, or what?

And while there were almost certainly elements of CYA in the post-Challenger investigation, I was referring to the pre-launch debate between Thiokol and NASA. It’s possible that politics played a role in THAT debate too, as Pres. Reagan was to give the SOTU address on the night of the 28th, and the administration supposedly wanted the launch to go ahead so they could have Ms. McAuliffe speak to the President live during the SOTU address. (Feynman’s book largely discounts this as a motivating factor though.)

And to address Julian’s comment — you could still make money by selling your contract BEFORE the launch date. For example, in the political futures market, if I had shorted Howard Dean futures the day before he made that Godawful “Yarrgh!” noise, then reversed the transaction a few days later, I would have made a killing. You don’t need to go right up to election day to make money. Similar transactions are conducted all the time in interest rate futures, commodity futures, etc. — you can make money just on the movement of the purchase price of the derivative itself.

Dale:

Is it not the case that most (or all) of the space programme thus far could have been achieved by way of unmanned flight? I always thought that astronauts were just a PR mechanism whereby NASA could capture the public imagination and keep the tax dollars flowing in.

In other words, had we gone the pure private sector route to space there would have been no deaths at all – just a lot more robots etc? Not a very romantic vision of life on the high frontier, I realise, but perhaps a cost-effective mission nonetheless.

Heck, if “cost effective” was in NASA’s playbook at all, we’d be firing off Saturn rockets to take care of a lot of this stuff. They spent $400m on a shuttle mission to recover a lost Hughes communication satellite that was insured for around $100m, as I recall. But in any event, there are far more cost-effective methods than the space shuttle for delivering low-priority payloads into space.

Mathew: The best I can say is: keep reading us for a few years. The topic you raise is so large that I would need almost a book length to properly reply. I suspect that I will write that material over time, just not all at once.

Let me say as a starter that when I say private sector, I am talking a NASA that remains NACA; a USAF that flies X planes and a private sector that builds from small to large boosters as the market requires them (I have long thought that the premature creation of large boosters pushed commercial satellites towards larger and fewer launches too early) and a manned space flight that builds directly off the X15 and leads to fairly regular and cheap access to space around the 1980 time frame. No Saturn, no Shuttle, no spam in a can.

I could go on, and I could explain all of this and more in exquisite detail with historical anecdotes… but it really would require a book.