One of the more feeble but less important things about the euro is the actual design of the banknotes. It was decided early on that the notes would show pictures of bridges, supposedly to symbolise “the close cooperation between Europe and the rest of the world”. However, due to the fact that there were not going to be enough notes to show a picture of a bridge from each Euro-zone country, the notes were instead designed with pictures of bridges that don’t actually exist, but which resemble (in terms of style) bridges that do exist somewhere in Europe. (To my eye, a remarkably large number of them resemble real bridges that are actually in France, but that might be just me). So, rather than drawing attention to the great cultural treasures that do in fact exist in the euro-zone, European money instead gives us a sort of homogenised blandless.

(Euro coins have one common side and one side that the country that would issues the particular coin into circulation can do what it likes with. Just as with the state quarters in the US, which the states got to design, the quality of the designs is variable).

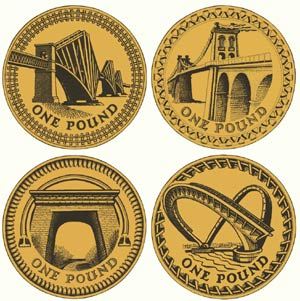

In any event, it was nice to see on the front page of this morning’s Times (which Samizdata does not link to) that the people who design British coins do not go for such blandness. From 2004 to 2007 Britain (assuming it does not join the euro) is going to release a series of four new pound coins showing great British bridges.

Of course, issues of everyone getting their turn come into this, too. As England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland all use the same coins, one of the four coins has to feature a bridge from each of the four constituent countries of the United Kingdom. (Curiously, the situation with the pound is the precise reverse of that with the euro. All of the UK uses the same coins, but England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland all have different banknotes).

This is where we get to the interesting part, which is the choice of bridges on the coins. Choosing for Scotland and Wales was undoubtedly very easy. Benjamin Baker’s Forth Bridge and Thomas Telford’s Menai Strait Bridge are so famous that it can’t have taken more than a moment to choose them. As for Northern Ireland, we have the rather more obscure Egyptian Arch from the Belfast-Dublin railway. Sadly, there are no really famous bridges in Northern Ireland, so we have to make do with what we have. I would rather a more famous bridge from somewhere else in the UK on the coin, but I guess Northern Ireland has to get a coin.

As for England, we have the very new Gateshead Millennium Bridge. This choice doesn’t impress me greatly, as I think the new bridge is more a piece of urban decoration than a piece of important infrastructure. (It illustrates that with modern super-strong materials, engineers and architects designing urban footbridges suddenly have immense freedom to be playful with the design of such bridges, as almost anything they can imagine has suddenly become technically possible and affordable. This is an interesting story, I am all for urban decoration, and I think the bridge is a very good example, but am not sure that this bridge is the right choice for a series of coins that celebrates great bridge building.

So what would my choice for the “England” bridge be? Well, the two most famous bridges in England (besides the unspeakably ugly Tower Bridge in London) are Abraham Darby’s Ironbridge in Shropshire and Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol. The Ironbridge is beautiful, and was utterly revolutionary when built. This would be my choice. The Clifton Suspension bridge is a great bridge built by Britain’s greatest engineer, but is very similar to the Menai Strait Bridge, and the Menai Strait Bridge was built first.

However, if you were to choose the Ironbridge as the fourth bridge, then you have chosen four bridges built between 1779 (The Ironbridge) and 1890 (The Forth Bridge). This isn’t that surprising, as this is the era during which British engineers led the world. However, I am guessing the coin designers decided they wanted something more contemporary for the fourth bridge. In the 20th century, bridge design came to be more and more dominated by the Americans, but British engineers still did some impressive things. As I see it, there were three major movements in the design of long bridges. One of these developments was the steel arch bridge. One of the most important examples of this type was designed by British engineers, but unfortunately it is in Australia. There are one or two examples of this type of bridge in the UK – most notably the Tyne Bridge in Newcastle, but there are much greater examples in Sydney and New York, so this has to be ruled out.

Bypassing the second for a moment, the third major movement in 20th century bridges was made possible in the 1980s by the same invention of new super-strong materials that gave the designers of pedestrian bridges their new freedom to exercise their every whim. This same materials revolution led to the cable stayed bridge becoming the most economical type to build for spans of up to about 1000 metres. Sadly, though, there are no particularly good examples of the type in the UK. The longest is the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge at Dartford, and the circumstances of the location prevented this from being an especially pretty bridge. In any event, the bridge was not particularly long or innovative by international standards. (There is a stunning example of this kind of bridge across the mouth of the Seine in France, however. If real bridges were being used for euro notes, I would definitely nominate this one. In fact they have put an imaginary bridge that looks quite like it on the 500 euro note).

So what have we left? Well, the second and most important 20th century movement for long bridges was the long span suspension bridge. The first two of these to be built were in the United States: the George Washington Bridge in New York and the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. However, there are three major bridges of this kind in the United Kingdom. The Forth Road Bridge is in Scotland, right next to the more famous rail bridge, so it doesn’t qualify for the English coin. (Also, it wasn’t a particularly innovative bridge, for reasons I will get to in a moment). The Humber bridge in East Yorkshire had until very recently the longest span of any bridge in the world (the record is now held by the Akashi-Kaikyo bridge near Kobe in Japan), and is a good piece of engineering, but not an especially exciting one. In any event, the amount of public money wasted on this fairly pointless bridge was so great that the Treasury is unlikely to want to constantly reminded of it.

The third long span suspension bridge in the UK is the First Severn Bridge, near Bristol. This bridge has a story.

In the early 20th century, suspension bridges got longer and longer, and their decks got thinner and thinner. This all went well until 1940, when the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in Washington State shook itself to pieces. It was then realised that the aerodynamics and resonance properties of bridge decks were not as well understood as engineers had thought. For a while, this problem was solved by attaching a thick metal truss to the bridge deck to make it rigid. However, this was expensive in engineering terms and looked ugly. (The Forth Road Bridge has such a truss, which is why I described it the way I did earlier).

Eventually, though, engineers did figure out the aerodynamic and resonance properties of Bridge design, and the Severn Bridge was the first long bridge built with a thin deck after the problems were properly understood. It is for this reason a significant bridge, as well as being a particularly beautiful bridge, especially at twilight, In my opinion it is the best bridge built in Britain in the 20th century. If not allowed the Ironbridge, this would be my nominee for the bridge to put on the “English” coin.

Except the Severn Bridge probably doesn’t qualify to appear on any of the four coins. The Severn Estuary marks the boundary between England and Wales, and while one end of the bridge is in England, the other is not. Personally I would still put it on the English coin, and insist that it had been chosen to emphasise “the close cooperation between England and the rest of the United Kingdon”. But the bureacracy probably couldn’t cope with this.

Despite all this commentary, I do like the design of the new coins, and very much look forward to actually seeing them in circulation. This is one more (relatively unimportant) reason to vote against the euro.

When I look at these coin designs, images from The Bridge by Iain Banks are popping in my brain. I am not sure that this is the desired effect.

Is it just me, or does that representation of the Gateshead footbridge look like a roller-coaster ride?

And you should have linked to a different page for the Ironbridge. The link on that page for the larger photo uses an irritating JavaScript command to keep it always on top. Whoever came up with that JavaScript command ought to be punished by having to listen to the the books-on-tape edition of the Collected Essays of Polly Toynbee. 🙂

Might I suggest this bridge…

http://www.roadtripamerica.com/places/havasu.htm

No, I suppose that just wouldn’t do! 😉

Other candidates for English bridges: Brunel’s Saltash Bridge, his Thames bridge at Maidenhead, Ribblehead viaduct.

MB: When Old London Bridge was replaced in the early 19th century, one engineer (Thomas Telford I think) proposed that it be replaced by a single iron arch across the Thames. If that one had been built, I think that London Bridge would be getting the coin now. (I also think that there would have been no need to replace it in 1962 it would still be carrying traffic across the Thames, and London Bridge would have thus never gone to Arizona). It’s one of the lost opportunities of engineering history, because it would have been a magnificent bridge.

All permitted bridges are fictional; all real bridges are banned. Highly symbolic of the European project’s close cooperation with the world we live in.

As far as I know the only bridge that physically links Europe to the rest of the world is on the Bosphorus. Which ain’t currently in the EU. But if enlargement proceeds to include Turkey, then it will be a bridge from Europe into the EU. Maybe that’s symbolic of something. Darned if I can see what…

Why did the turkey cross the bridge?

Interesting stuff Michael, thanks.

The River Wye separates England from Wales. The Severn, although rising in Wales, flows through England for most of its trip to the Bristol Channel. I think it could just get on the English coin because its western end actually lands on a spit between the Servern and the Wye before continuing on into Wales as one can see here.

However as a Plymouthian I’d agree with Tim Hall and go for Brunel’s fantastic Tamar Bridge, hey even the Luftwaffe liked it so much they used to take pictures of it.

Impartially Iron Bridge should have got it in my view.

back pedal – back pedal – back pedal

Only half of the Tamar Bridge is Angleland. The rest is in the Duchy of Cornwall, which has as much of claim to be a country in its own right as Wales does.

Is Cornish a Celtic language? I would guess so, but I realise I have absolutely no idea if this is so. (Yes, I could no doubt look it up)