We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

Freedom/liberty is defined in different ways. Some people talk of “free will” of agency, of the ability (sometimes and to some extent) to choose. Of how human beings are just that (beings) not flesh robots whose actions are either determined by a process of causes and effects going back to the start of the universe or are a matter of random chance (neither determinism or random chance being agency – being human choice).

This is not the place to debate the existence of the “I” (the reasoning, self aware, self) and to argue that agency is not an “illusion” (although if it is a illusion who is having the illusion – humans being simply being flesh robots), but I will say that if humans are not “beings” (not agents) then freedom is of no moral importance. No more than it is of moral importance whether water is allowed to “run free” or constrained behind a dam. But then, of course, if there is no agency (no freedom of choice) then there is no morality anyway. A clockwork mouse does not have moral responsibility – and neither would something that looked like a human being but was, in fact, not a “being” (an agent – a choosing “I”) at all.

As for the position that it is “compatible” that a human might have no capacity what-so-ever to choose any of their actions (including lines of thought) and yet still be morally responsible for them – well it is not compatible, basic logic does not allow us to have our cake and eat it as well.

Others talk of freedom in terms of stuff – goods and services.

Such people may or may not accept that humans have the capacity (sometimes to some extent) to make real choices – but they hold that even if humans do have the ability to make choices this does not mean they should be allowed to.

People will make the wrong choices – they will do things make the world a worse place, even for themselves.

To some extent the political libertarian actually agrees with that – after all we do not believe that people should be allowed to make the choice to rob, rape or murder other people.

Or, rather, they should be allowed to make the choice – but not to act on it (aggression should be opposed), and they should be punished if they do act upon it.

Some people have suggested that we be called “propertarians” (rather than libertarians) because of our opposition to chosen actions that aggress against the bodies and goods of people – to which my response is “if you want to call me a propertarian do so – I do not take it as a insult”.

However, the political libertarian (such as myself) tends to deny that non-aggressive choices – choices that respect the bodies and goods of other people, tend to be “wrong” in general.

We hold that most people, most of the time are more likely to get things right than the “great and the good”.

Not just “were you ten times and wise you would not have the right to impose your plans upon myself and others”, but also “even if you were ten times as wise you would still muck it all up”. Indeed it would be claimed that the clever elite are not “wise” at all – for if they were “wise” (rather than just clever) they would understand that trying to “plan society” always ends badly.

In part at this point we move from philosophy to political economy – economics… → Continue reading: The rise and decline of freedom in Britain – the decline and rise of the State

Travel books, or adventure books chronicling experiences of living abroad, can be highly variable in literary or other qualities. I have my favourites: I loved that PJ O’Rourke classic, “Holidays in Hell”; I enjoyed the travel and memoirs of the great Patrick Leigh-Fermor, and another favourite of mine was Eric Newby’s The Last Grain Race (describing his experience of sailing aboard a four-masted clipper-type ship). Being a bit of a yachtie, I also enjoyed the Robin Knox-Johnson account of his single-handed sailing trip around the world. And of course there are military memoirs where adventure and travel are co-mingled with armed expeditions. And a case in point is the writing of Norman Lewis.

I have not read much by Lewis, who died at the grand age of 95 after having spent a rich and varied career in places ranging from Brazil, Indonesia to Western Europe. And perhaps his most celebrated book is “Naples ’44”, describing his year in the southern Italian city in the immediate aftermath of the Allied landings in Italy. It is a superbly written account – Lewis has a wonderful eye for detail – and conveys the sheer bloody awfulness of life for ordinary Italians recovering from both the invasion and the Fascist regime that had been dislodged. For example, his descriptions of how little food the populace had, and what they had to eat, is sobering indeed to anyone reading moral-panic journalism about our supposed obesity crisis.

Of course, any account of southern Italy will include tales of the Mafia, and banditry, and the relentless amounts of corruption. What is particularly striking – and this is where the libertarian in me gets interested – is how the black market for stolen Allied goods, such as penicillin – thrived. Naturally, with so many goods suppressed or in short supply, criminal gangs and bent military personnel sought to make a market. This highlights how when markets are suppressed and where the fabric of civil society has been smashed by war, thugs can often fill the gap. In some cases, theft of supplies from the Allied forces got so bad that Lewis and his colleagues had to do something about it. Ordinary Italians who got caught pilfering supplies often received long jail sentences; well-connected businessmen (ie, Mafia guys), were acquitted when witnesses suddenly failed to show up.

Lewis became something of an expert on the Mafia and this region of Italy. He does not romanticise what he saw – he was too lacking in fake sentimentality for that. I have sometimes heard fellow free marketeers liken government to a sort of Mafia – tax is a kind of legalised thievery – but I am not sure it is an analogy I would push too far. I wonder how many of us would have wanted to live in Mafia-run Sicily or the neighbouring mainland, even with the tasty wine, olives and sunshine.

I intend to read a lot more of Lewis’s output. His writing is wonderful.

A literary work, whether it be fiction or non-fiction, a brief essay or a lengthy treatise, should be composed with constant attention to the underlying theme of the work, summarised if possible in one sentence. I have borne this precept in mind. The message that integrates the text of this biography is that one man, relying on reason, and daring to stand alone, can make a difference in the world.

– The last paragraph of the preface of Dare To Stand Alone, Bryan Niblett’s biography of nineteenth century atheist, republican, birth control advocate and radical individualist, Charles Bradlaugh. Niblett spoke eloquently about Bradlaugh last night in London, at the most recent of Christian Michel’s 6/20 evenings.

It has been good to get out of the UK this Christmas. As one or two Samizdata regulars will know, I had a crap December as my dear mother, at the relatively young age of 69, died of cancer on 9 Dec. I just needed to get away and decompress and gather my thoughts.

Fortunately, I have wonderful relations via my wife who work with the US military in Southeast Germany, about 20 km from the Czech border. They are a great group of folk who know how to put on a good Christmas. Bavaria has been spectacular due to all the heavy snowfall. It has seen temperatures as low as -18 Degrees.

One of the places I visited was a museum all about a huge US army base near the small German town of Grafenwoehr. The place dates back to the start of the 20th Century, when the then German government built it up and it remained in German hands until the Allied armies, with Patton’s 3rd Army to the fore, captured it at the end of WW2. During WW2, for example, the place was used by the various groups within Hitler’s armies for training purposes. Himmler gave a speech there. During WW1, it was used, among other things, as a PoW camp. Many soldiers are buried there. Later, during the Cold War, even the likes of a young Elvis Presley did some army training on the base.

Going on the base with a relation of mine, the place seems so pristine and businesslike with lots of US servicemen and women getting ready for deployments to the MidEast. I wonder what they think about the uses to which this huge training area has been put in the past. It is, so I am told, the biggest US army training facility outside of the US. Of course, a lot of bases have been closed down since the early 1990s, but the presence of NATO forces is still evident, judging by the various North American accents I hear in the local shops and restaurants.

I can strongly recommend this part of Southern Germany as a place to visit. The locals are very friendly and the economy is, judging by a massive shopping mall in Regensburg, buzzing. And the local beer is awesome. What more excuse do you need?

“But his [Peel’s] chosen remedy for widespread poverty was already apparent. It did not lie in changing the Poor Law, or reducing factory hours through a Ten Hour Bill, or in accepting the irrelevant political demands of the Chartists. Still less did it consist in commissioning that engine of public welfare and State guidance of the economy to which we became accustomed in the twentieth century. Peel and most of his contemporaries would have regarded our giant complex of State machinery as a destructive restraint on individual freedom.”

Robert Peel, page 243, by Douglas Hurd.

Indeed they would have so regarded the modern state of the late 20th and 21st centuries. And with good reason. Somehow, I doubt that even the founder of the Metropolitan Police would have liked the idea of the modern Surveillance State. I am not too sure that he’d have been all that keen on top tax rates of 50 per cent and more, compulsory schooling to the age of 18, or the hideously regulated labour market of today.

And this historical shift, I think, can explain to a certain extent why, to a British audience dulled by decades of socialism, the sight of Americans protesting against Big Government and the like is so odd. Last night, on the BBC, the broadcaster and one-time Sunday Times (of London) editor, Andrew Neil, was looking at the Tea Party movement. It was not all bad as a documentary – he had a great short interview with the son of Barry Goldwater – but in the main, the general idea that the viewer was meant to draw was that the Tea Party movement was comprised mainly of cranks, bigots and fools. The problem, I think, is that Britain has not really had a genuine, tax-cutting protest movement since the anti-Corn Law League of the 1830s and early 1840s, which is why I was so struck by that passage about the Peel administration. We have to go back to the early years of the Industrial Revolution to find anything remotely like such a protest for government retrenchment and tax cuts. No doubt Mr Neil would regard Cobden, Bright, or indeed Peel himself, as a bunch of nutters.

And that, of course, is why the accurate teaching of history, such as around such episodes as the Industrial Revolution, is so important.

[with apologies to the Four Yorkshiremen]

A fantasy writer produced this:

But there’s a dark side as well. We know about the real world of the era steampunk is riffing off. And the picture is not good. If the past is another country, you really wouldn’t want to emigrate there. Life was mostly unpleasant, brutish, and short; the legal status of women in the UK or US was lower than it is in Iran today: politics was by any modern standard horribly corrupt and dominated by authoritarian psychopaths and inbred hereditary aristocrats: it was a priest-ridden era that had barely climbed out of the age of witch-burning, and bigotry and discrimination were ever popular sports: for most of the population starvation was an ever-present threat. I could continue at length. It’s the world that bequeathed us the adjective “Dickensian”, that gave us a fully worked example of the evils of a libertarian minarchist state, and that provoked Marx to write his great consolatory fantasy epic, The Communist Manifesto. It’s the world that gave birth to the horrors of the Modern, and to the mass movements that built pyramids of skulls to mark the triumph of the will. It was a vile, oppressive, poverty-stricken and debased world and we should shed no tears for its passing (or the passing of that which came next).

Oh really? Try this from the Old Bailey’s website:

1760-1815

From approximately three-quarters of a million people in 1760, London continued a strong pattern of growth through the last four decades of the eighteenth century. In 1801, when the first reliable modern census was taken, greater London recorded 1,096,784 souls; rising to a little over 1.4 million inhabitants by 1815. No single decade in this period witnessed less than robust population growth.

In part this urban bloat resulted from a marked decline in infant mortality brought about by better hygiene and childrearing practices, and a changing disease pattern. By the 1840s children born in the capital were three times less likely to die in childhood than those born in the 1730s.

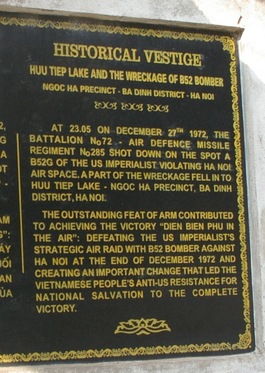

Hanoi, Vietnam. October 2010

Apparently, it takes about a third of a century for the remains of a B-52 that fell into a lake after being shot down to turn into an interesting piece of municipal sculpture in a nice part of town.

Okay…

It may be surprising to present-day readers to think that it was once thought a “soft option” to transport a convicted criminal to a colony such as Australia’s Botany Bay. But as this letter shows, that is what some influential people thought at the time:

“the sentence of the Court is that you shall no longer be burdened with the support of your wife and family. You shall be immediately removed from a very bad climate and a country over burdened with people to one of the finest regions of the earth, where the demand for human labour is every hour increasing, and where it is highly probable you may ultimate regain your character and improve your future. The Court has been induced to pass the sentence upon you in consequence of the many aggravating circumstances of your case, and they hope your fate will be a warning to others.”

Sydney Smith, Whig clergyman and wit, as quoted in Robert Peel, by Douglas Hurd, page 78.

As an aside, Peel was involved in two issues – re-connecting bank notes to bullion, and the 1844 Bank Charter Act – that have enduring relevance to our own time. Hurd’s biography is very readable and has a nice tone to it; in my view, however, Norman Gash’s study remains the definitive one.

There have, as I might expect, been a flurry of reviews about a recent biography of Harold Macmillan, who – to those non-Brit readers who might not have heard of him – was prime minister in the late 1950s through to 1963, and who was involved in controversies that hung over his head until his very old age, such as the issue of his alleged involvement in sending Cossack forces back to the tender mercies of Stalin at the end of WW2. He was a complex and interesting character in many ways; my mother remembers his nickname of “Supermac” and the extraordinary period in the early 1960s when the Profumo Scandal broke, as well as Macmillan’s own resignation through ill health and the subsequent emergence of Alec Douglas Home as leader. Home, let it not be forgotten considering how he was mercilessly lampooned by parts of the leftist press, almost won the 1964 general election.

One review here by Simon Heffer more or less sums up my own views of the man. Heffer recognises that for all Macmillan’s undoubted merits – he was, for example, an extremely brave army officer wounded several times in the First World War – that he was a decidedly flawed politician in certain respects, particularly on the crucial issue of economic policy and industrial relations. The 1950s and 60s saw the rise of what was to be dubbed the “British disease” – a time of rising industrial strife, inflation, low productivity, endless “stop-go” cycles of Keynesian-inspired reflation followed by subsequent slamming on of the monetary brakes. And while it would be grossly unfair to pin too much blame on one prime minister for the sort of problems that eventually came to a head in the 1970s, he must take some share of the responsibility for the mess that was eventually addressed – after a fashion – by Mrs Thatcher’s administration in the 1980s. And yet the impression I get from Heffer’s review, and particularly, this one by Peregrine Worsthorne, is that the biography more or less absolves Macmillan of any blame whatever. Worsthorne’s review in the Spectator – behind a subscription firewall – carries this, for instance:

“He was right to have himself been the main political champion of his old friend Keynes and his economics.”

Oh dear. Fell asleep during the 1970s, did we?

He also says that Macmillan was right to have played down the danger of the Soviet Union during the Cold War. I am not sure that is really true, but if it was true, is that to his credit? With the benefit of hindsight, the Soviet Union was a rotten house that looked imposing with all its mass Red Square parades and all the rest but eventually crumbled very fast, but at the time, it did not seem that way, and some very supposedly clever people, such as that Keynes fan (!) JK Galbraith, were arguing as late as the early 80s that there was no real difference economically between the West and the Soviet Empire. And the sheer size of the Soviet armed forces, and the way that the Hungarian and Czech revolts were harshly suppressed, hardly squares with the idea that that Empire could be treated with a sort of shrug of the shoulders. By the way, for a dose of good sense on the Cold War years, I recommend this by Norman Stone.

But perhaps the most ludicrous aspect of Worsthorne’s review is this part, in which he writes mournfully of what might had been had Sir Alec Douglas Home won in 1964:

“This would have spared us both the Thatcher interlude, which put power in to the greedy hands of what Macmillan called the ‘banksters’, and then the Blair/Brown years, which entrusted it to the equally grasping and disreputable New Labour cabal, which purported to be a meritocracy. But it is beginning to look as if a promising reaction has set in – not too late one hopes – and although David Cameron is not exactly a 14th earl, he is the next best thing, so Uncle Harold must be cheering in his grave.”

I am going to do Worsthorne the respect of assuming he is sane, and serious, when he wrote that somehow, Mrs Thatcher’s time in office was some sort of ghastly “interlude” when the rightful aristocratic rulers of us unwashed were horribly pushed aside by a bunch of grammar school educated City slickers and Jewish intellectuals. Macmillan once infamously said that he regretted there were more Estonians than Etonians in the Tory Cabinet of the time, a particularly nasty little line. Sure, the attack on the Blair and Brown bunch is perhaps more deserved, but let’s not forget that Blair was a Fettes public schoolboy, and a good many of Mrs Thatcher’s ministers came from smart backgrounds.

In fact, when all is said and done, what Worsthorne rates as Macmillan’s greatest achievement, is contained in the opening paragraph of his review. I leave readers with this to ponder:

“Since the main purpose on earth of the Conservative Party was, and still should be, to keep Britain’s ancient and well-proven social and political hierarchy in power – give or take a few necessary upward mobility adjustments – Harold Macmillan must rank very high in the scale of successful Conservative prime ministers; just below Benjamin Disraeli, whose skill in sugaring the pill of inequality and humanising the face of privilege is never likely to be bettered.”

In other words, whatever Macmillan may or may not have done to stem the UK’s post-war economic decline, at least he kept the toffs on top.

Words fail me.

On this day in 1805, a famous signal was sent in the context of the struggle against an earlier iteration of pervasive European Union.

I am reading a review of this book (thank you Instapundit), about Stalin and Hitler and their many and mutually supportive crimes, and I came upon a fact that was very surprising to me:

About as many people died in the German bombing of Warsaw in 1939 as in the allied bombing of Dresden in 1945.

Here in Britain we remember, those of us who are the remembering sort, Winston Churchill’s metaphor-mangling talk of winds and whirlwinds, sewing and reaping. Relatively mild bombing of British cities by the Luftwaffe was followed later in the war by truly horrific bombing of German cities by the RAF.

But that original wind, in other parts of Europe, was windier than I had realised.

LATER: And here’s another little fact that pulled me up short:

In just a few days in 1941, the Nazis shot more Jews in the east than they had inmates in all their concentration camps.

Although, I am not clear whether that is inmates in camps at that time, or inmates in camps over the whole period. The former, I think. Either way, it is hideous. Not sure I want to read the entire book. I already get the general idea.

You never stop learning strange things, do you? For instance, this morning, I was (still am) listening to CD Review, and the presenter Andrew McGregor suddenly starts talking about how, in the year 1612, the heir to the throne, James I’s son Prince Henry, rather foolishly went for a swim in the Thames, caught typhoid, and died. Cue an “outpouring of grief”, which included songs about the death of the young Prince (aged 18), hence the CD angle.

And who became king of England instead? Why, only Charles I, who got himself executed in 1649, in the midst of a ferocious civil war between himself and his severely angered Parliament. That I had heard about. Prince Henry was apparently, and in fascinating contrast to his younger brother, a Protestant:

Henry was quite the Protestant – when his father proposed a French marriage, he answered that he was ‘resolved that two religions should not lie in his bed’.

You can’t help wondering: What If? What if Prince Henry had not gone for that swim, and had become the King instead of Charles I? How might English history have turned out then?

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|