We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

“There was never any widespread popular demand for change, and the argument that people would find a decimal system easier was true in practice only of those who rarely used it, i.e., foreigners. From an educational point of view, our duodecimal system was preferable because it taught children how to count in different bases. People brought up before decimalisation are almost invariably better at mental arithmetic than those born since. When we lost our shillings and pence, as when, more gradually, our weights and measures were subverted, we lost the full meaning of many of our nursery rhymes, jokes and proverbs. We also lost the actual coins, all of them superior in design to what replaced them and all, because they remained in circulation so long (it was common in the 1960s to receive a Victorian penny in change), of historical interest. Indeed, this is literally true, since the inflation of the Heath/Wilson years made the new coins almost valueless.”

Charles Moore, Spectator, page 11, 19 February edition (behind the subscriber firewall).

He is right on this. Yes, I can see some readers sniffing that a lot of old rot about rhymes and so on is hardly any reason for keeping a form of coinage, but I think he has a point about different bases in counting; even in my own field of finance and banking, I noticed that in some areas, such as the pricing of US bond securities, the practice was recently, or still is, to mark prices in sixteenths and 32nds, rather than in the decimal form used for Eurozone bonds, for example. And being able to do this is good for my maths – not a strong point.

But the broader issue surely, is that while the loss of old coinage may be upsetting to traditionalists, the real nub of the matter is that there is no point in embracing some “modern” standard of counting or whatever if the government, and central bank, debauches the currency. And unfortunately, even during the “good old days” when old coinage existed, the quackery of inflationism was eroding the value of those pounds (a unit of weight, remember) and everything else. I would settle for any coinage system so long as it retained its value.

What killed respect and affection for money was not the decimalisation mania of the late, unlamented Sir Edward Heath. It was inflation.

I sometimes pick up quick-to-read paperbacks, either fiction or non-fiction, at airports to help pass the time during my flight. So, on a recent short break to Malta, I bought Dambisa Moyo’s How the West Was Lost, published a short while ago, which seeks to argue that for various reasons, good and bad, the West (essentially, Western Europe and North America) is in danger of losing out to the East. I was intrigued enough to pay a few quid for the book, but in the end I should have known better.

Moyo has a lot of things to say with which free marketeers might approve of: she denounces the way in which the banking system has encouraged over-use of debt financing, creating all manner of problems, culminating in the sub-prime mortgage disaster and associated asset price bubble; she also understands that modern Welfare States have created many problems. However, for all that she tries to accept that the rise of the former Third World nations from poverty is a Good Thing and to be applauded, I cannot help but feel that she does not really mean it very much. She’s a mercantilist who sees economics as a titanic fight between states and is hostile, or at least sceptical, about the capacity of people operating in markets under the rule of law. And she repeats the canard that the panic of 2008 demonstrated the dangers of unfettered capitalism, oblivious to the fact that the monetary policies of the Fed, etc, were policies of state institutions, as was the interference in the US and other housing markets by governments (Freddie Mac, etc).

In fact, she seems wedded to a sort of neo-Malthusian argument that says that the desire for prosperity and higher living standards in places such as China is unmitigated bad news for the West as there are finite resources in energy, etc, and that Eastern prosperity comes at the expense of the West’s. In other words, she is arguing that economics is, in some ways, a case of winners and losers. Indeed, she talks repeatedly about the idea of there being a race, often using the very word… “race”… to make her points.

Here is one typical paragraph in which she says the West is suffering from all that terrible selfish individualism and we should benefit from a bit more of that no-nonsense collectivism as seen in China (page 172):

“Frankly speaking, the constitutional framework that has defined the US for the past three centuries is not likely to be amended in order to hand over more power to the state. Yet arguably more power, more flexibility and fewer committees are exactly what is needed. What sense does it make in the depths of the financial crisis – a state of economic emergency by most accounts, which brought the country and the world to its knees – for the President of the United States to have to build consensus around a desperately needed fiscal stimulus package before he and his advisors can act?”

She seems curiously unaware of to what extent the powers of the Federal government in the US have already gone way beyond what was envisaged by the Founders – and that’s a bad thing – and that in other Western nations, such as the UK, the government of the day has considerable powers, or has yielded great powers to the European Union and its legions of unelected officials. And yet for Ms Moyo the problem is that is far too much of this pesky liberalism, checks and balances, and so forth. I hate to say it, but she’s coming close to flirting with a form of fascism.

There are other, equally poor, arguments. For instance, she argues that the vast majority of citizens in Western nations have only reaped a small share of the benefits of greater trade and so on because many of the profits earned are paid to shareholders. For instance: (page 178) “The only thing companies were interested in was the company’s profitability and therefore the shareholders’ return on capital.”

Wow, the owners of firms want to make a profit (as opposed to making a whacking great loss, presumably). But even this line ignores the fact that by “shareholder”, we do not just mean a few isolated fat, capitalist bastards in suits; no, we also mean all the millions of people – including people a bit like Ms Moyo – who have savings plans, 401K plans, mutual funds, pension pots, etc. This line of hers also does rather beg the question of what should happen to these profits – should they be taxed in “reinvested” by governments? In several instances, she praises the behaviour of governments, such as oil-rich states, and their massive “sovereign wealth funds”, arguing that these are used to benefit domestic populations. Well they may be in some cases, but even a cursory awareness of public choice economics should alert Ms Moyo to the dangers of corruption, mis-allocation of capital, political favouritism and faddism that often comes when government agencies disburse vast sums. The flashy public spending projects of the past have often brought dubious rewards.

And I just knew I had wasted my aircraft reading time when she scorned Ricardo’s Law of Comparative Advantage, arguing that unless all countries play “fair” (which never happens), then the argument for free trade that the LCA underpins is chucked away.

This argument – that free trade is only beneficial if everyone plays nice – has been demolished time and again. A good example comes from Deepak Lal, in his book, Reviving the Invisible Hand.

Here is a passage:

“a country will benefit from removing its own tariffs and import restrictions even if all its trading partners maintain theirs. For as long as the domestic prices of goods in our country under autarky differ from those at which they can be imported and exported under free trade, the country will be able to obtain the gains from trade both by obtaining imported goods at a lower cost than they are produced at home (the consumption gain) and by specialising in producing and exporting those goods in which it has a comparative advantage and importing the others (the production gain), irrespective of the tariff applied by their trading partners. For these trade restrictions only damage the protectionist country’s welfare, and it would be senseless not to improve one’s own welfare just because someone else is damaging theirs. There is no point throwing rocks into one’s harbour just because others are throwing rocks into theirs. Hence, there is an incontrovertible case for every country to unilaterally adopt free trade, irrespective of the protectionist policies of other countries – with one exception. Suppose that a country is the only producer of some good – say, oil.”

He goes on to explain this case but says that in fact, retaliatory trade practices and other issues take the edge off this argument also.

It is all such a pity. She started well, but I really wish I had read that new Lee Child thriller instead.

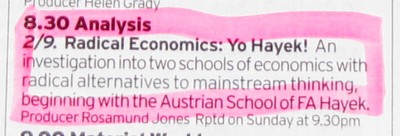

As in BBC Radio 4, this coming Monday, January 31st, 8.30 pm:

That’s from the current Radio Times. As you can tell from the pink, I will be paying close attention. My thanks to fellow Samizdatista Chris Cooper for alerting me to this radio programme.

But will it be an attempt at a hatchet job? It seems not:

This week, Jamie Whyte looks at the free market Austrian School of F A Hayek. The global recession has revived interest in this area of economics which many experts and politicians had believed dead and gone. “Austrian” economists focus not on the bust but on the boom that came before it. At the heart of their argument is that low interest rates sent out the wrong signals to investors, causing them to borrow to spend on “malinvestments”, such as overpriced housing. The solution is not for government to fill the gap which private money has now left. Markets work better, Austrians believe, if left alone. Analysis asks how these libertarian economists interpret the state we’re in and why they’re back in fashion. Is it time to reassess one of the defining periods of economic history? Consensus would have it that the Great Depression of the 1930s was brought to an end by Franklin D Roosevelt’s Keynesian policies. But is that right? Jamie Whyte asks whether we’d all have got better quicker with a strong dose of Austrian medicine and whether the same applies now?

I think I first encountered Jamie Whyte at a Cobden Centre dinner.

I was disappointed with the recent Robert Peston TV show about the banking crisis, despite appearances on it by Toby Baxendale, the founder of and Chairman of the Cobden Centre. All the fault of the banks was the basic message, with governments looking on helplessly. No mention (that I can now recall) of those same governments monopolising the supply of money and relentlessly determining the price of borrowing it, all day and every day, all the time.

But, my understanding of Baxendale and of the Cobden Centre is that he (it) is playing a long game, giving broadcasters whatever they ask for (in Peston’s case Baxendale messing about with fish), while all the time asking them to give the Cobden Centre’s ideas at least something resembling a decent hearing. Don’t compromise on the ideas, but be endlessly mellow and accommodating at the personal level, intellectual steel in velvet glove, and so on and so forth. If that’s right, then it may be starting to work.

John Hawkins: Now, in recent years we started to hear more people calling to get rid of the Federal Reserve. Good idea, bad idea? What are your thoughts?

Thomas Sowell: Good idea.

John Hawkins: Good idea? What do you think we should replace it with? What do you think we should do?

Thomas Sowell: Well it’s like when you remove a cancer what do you replace it with?

Indeed. And not just the price of all the other kinds of gas.

Am I the only one who suspects that a lot of the climate change hubbub whipped up in recent years was really just a cover for getting young lefty-inclined scientists to find other kinds of energy, not actually to save the planet, but rather to enable the rulers of the West to tell those pesky Arabs to take a hike? I don’t read the right sort of blogs and websites to know for sure, but I doubt very much that I am.

Anyway, now, another kind of energy has come on stream, of the sort that conflicts with all the climate change hubbub, because it is disturbingly similar in its imaginary climatic effects to the stuff that our rulers want to be able to stop buying from the Arabs.

The BBC’s Roger Harrabin quotes the Chief Economist at the International Energy Association, Dr Fatih Birol:

“There’s suddenly much more gas available in the world than previously thought,” he told BBC News.

“It’s cheaper than it was and the supply is more assured. And it’s only half as polluting as coal. There will be strong debates between energy and climate and finance ministries round the world about whether investment should continue to support renewables when the situation on gas has so radically changed.”

That settled science is already turning out to be not so settled after all, and this just might be part of the reason, don’t you think? Governments, for their own reasons that have nothing to do with the actual argument, are now switching from being climate change fanatics to what the climate change fanatics call climate change deniers.

The moral is: if you want to spread some ideas, any ideas, don’t rely on governments to help you. They will help you, if and while it suits them. But if and when it stops suiting them, you’d better be ready to win your argument all by your little old self.

The other night, when I had the TV on, I saw that one of the programmes, featuring the BBC top economics and business correspondent, Robert Peston, was all about the financial panic of recent years. Oh dear, I thought, I can just imagine the usual line about how it was all the fault of greedy bankers, insufficient regulation, “unregulated laissez faire capitalism”, and on and on. Well, not quite. Yes, some of those elements were there, but there was also quite a lot of sophisticated explanation of how a combination of forces – leverage, “too big to fail bailout protection, over-confidence in newfangled ideas of risk management and misalignment of incentives for bankers – combined to create the storm. I would have liked to see more focus on the role of ultra-low central bank interest rates in creating the crisis, as well as government intervention in the housing market and through deposit insurance, but to be fair, this was mentioned, several times. There was little in the show with which someone like Kevin Dowd, recently referred to here, would dispute, although I imagine Kevin might want to make more about the vexed issue of ownership of banks and limited liability.

And about three-quarters of the way into the show was Toby Baxendale, founder of the Cobden Centre, the organisation founded last year to flag up the problems caused by central banking fiat money, and which sets out alternative ideas, such as the possibility of giving depositors in no-notice cash accounts the right to demand that their cash is properly looked after, not lent out for months in a risky play. (Yup, it is that pesky fractional reserve banking issue again). Toby was very forceful and his views were treated respectfully by Peston. There was no sneering.

In short, this was and is a pretty good programme as far as the MSM goes. I give it about 8 out of 10. Yes, I am not drunk.

“If you wanted to fly and there were no supervisory authority in the airline industry and no regulations enforcing safety standards, you would be very reluctant to fly fledgling airlines. You would prefer the established ones that had the track record and the reputation. So a complete lack of safety regulations in the airline industry would favour established firms, making the entry of new ones impossible and killing competition and consumer choice.”

Raghuram G. Rajan and Luigi Zingales, from page X (in the Roman numeral segment) of “Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists.” Published in 2003.

This is an interesting defence of government-imposed safety standards. I am not wholly convinced by this line of argument; it is, for sure, an interesting way of trying to show how government regulation actually stimulates rather than restricts entry into a particular line of business.

My take is that if a fledgling airline, say “Ultra-Cheap Airlines Inc.,” can persuade investors and others to get it started in business with a few aircraft and so on, then the staff on the aircraft – such as the pilots – will not set foot into an aircraft if they fear that safety has been compromised, or if the aircraft are poorly maintained. Pilots are not usually self-destructive, as far as I can tell. In fact, a debutant airline business would bend over backwards to show customers that it had set high standards, get consumer watchdog organisations and other certification providers to give it a “seal of approval”. What the authors of the quote don’t seem to understand is how the “established” airlines got to be in that positions in the first place. Presumably, they had to start by persuading a highly nervous customer base that flight was safe, or at least, not lethal.

And of course, if the standards imposed by regulators are particularly onerous, then it is hard to see how a small business operating a few aircraft could afford to compete with the big boys. Regulations are a form of barrier to entry, much in the same way that extensive licensing of doctors is designed, quite deliberately, to regulate the number of people working as physicians.

This book is generally pretty good, however; it is interesting to read this book alongside the Martin Hutchinson/Kevin Dowd book about financial markets that I quoted the other day.

I know, my friends, that you are concerned about corporate power. So am I. So are many of my free-market economist colleagues. We simply believe, and we think history is on our side, that the best check against corporate power is the competitve marketplace and the power of the consumer dollar (framed, of course, by legal prohibitions on force and fraud). Competition plays mean, nasty corporations off against each other in a contest to serve us. Yes, they still have power, but its negative effects are lessened. It is when corporations can use the state to rig the rules in their favor that the negative effects of their power become magnified, precisely because it has the force of the state behind it. The current mess shows this as well as anything ever has, once you realize just what a large role the state played. If you really want to reduce the power of corporations, don’t give them access to the state by expanding the state’s regulatory powers. That’s precisely what they want, as the current battle over the $700 billion booty amply demonstrates.

This is why so many of us committed to free markets oppose the bailout. It is yet another example of the long history of the private sector attempting to enrich itself via the state. When it does so, there are no benefits to the rest of us, unlike what happens when firms try to get rich in a competitive market. Moreover, these same firms benefited enormously from the regulatory interventions they supported and that harmed so many of us. The eventual bursting of the bubble and their subsequent losses are, to many of us, their just desserts for rigging the game and eventually getting caught. To reward them again for their rigging of the game is not just morally unconscionable, it is very bad econonmic policy, given that it sends a message to other would-be riggers that they too will get rewarded for wreaking havoc on the US economy. There will be short-term pain if we don’t bailout these firms, but that is the hangover price we pay for 15 years or more of binge lending. The proposed bailout cannot prevent the pain of the hangover; it can only conceal it by shifting and dispersing it among the taxpayers and an economy weakened by the borrowing, taxing, and/or inflation needed to pay for that $700 billion. Better we should take our short-term pain straight up and clean out the mistakes of our binge and then get back to the business of free markets without creating an unchecked Executive branch monstrosity trying to “save” those who profited most from the binge and harming innocent taxpayers in the process.

What I ask of you my friends on the left is to not only continue to work with us to oppose this or any similar bailout, but to consider carefully whether you really want to entrust the same entity who is the predominant cause of this crisis with the power to attempt to cure it. New regulatory powers may look like the solution, but that’s what people said when the CRA was passed, or when Fannie and Freddie were given new mandates. And the very firms who are going to be regulated will be first in line to determine how those regulations get written and enforced. You can bet which way that game is going to get rigged.

I know you are tempted to think that the problems with these regulations are the fault of the individuals doing the regulating. If only, you think, Obama can win and we can clean out the corrupt Republicans and put ethical, well-meaning folks in place. Think again. For one thing, almost every government intervention at the root of this crisis took place with a Democratic president or a Democratic-controlled Congress in place. Even when the Republicans controlled Congress, President Clinton worked around it to change the rules to allow Fannie and Freddie into the higher-risk loan market. My point here is not to pin the blame for the current crisis on the Democrats. That blame goes around equally. My point is that hoping that having the “right people” in power will avoid these problems is both naive and historically blind. As much as corporate interests were relevant, they were aided and abetted, if unintentionally, by well-meaning attempts by basically good people to do good things.The problem is that there were a large number of undesirable unintended consequences, most of which were predictable and predicted. It doesn’t matter which party is captaining the ship: regulations come with unintended consequences and will always tend to be captured by the private interests with the most at stake. And history is full of cases where those with a moral or ideological agenda find themselves in political fellowship with those whose material interests are on the line, even if the two groups are usually on opposite sides.

– Professor Steven G. Horwitz, writing in late September 2008, in a piece entitled An Open Letter to my Friends on the Left. This evening, Horwitz will be giving a talk at the Institute of Economic Affairs in London, entitled An Austrian Perspective on the Great Recession 2008-2009.

“It might be more appropriate if the Sveriges Riksbank would end the Economics Nobel Prize as a failure: strictly, it isn’t a true Nobel at all; it was not part of Alfred Nobel’s legacy, but a much later add-on to pander to the economics profession’s vain pretensions of scientific respectability. If we judge a science by the hallmark of predictability, then the predictions of economists are no better than those of ancient Roman augurs or modern taxi drivers; alternatively, we can judge by its contribution to “scientific” knowledge, in which case the contribution that modern financial economics has made makes us wonder if the agricultural alchemist Lysenko shouldn’t have got a Nobel himself; or we can judge it by contribution to the welfare of society at large, in which case the undermining of the capitalist system, the repeated disasters of the past 20 years, the immiseration of millions of innocent workers and savers, and the trillion dollar losses of recent years surely speak for themselves.”

– Alchemists of Loss – How Modern Finance and Government Intervention Crashed the Financial System, by Kevin Dowd and Martin Hutchison. First published in 2010. Page 86.

Now having read it, I cannot recommend this book too strongly. Some of the discussion about modern financial theory – and its baleful consequences – is quite complex, but the authors write with a verve and eye for drama that makes this a very readable book. In my view, it is the best study of what has happened, and more importantly, spells out in practical, thoughtful ways as to what should be done.

“But I detect that the criticism [of big businesses] is increasingly out of date, and that large corporations are ever more vulnerable to their nimbler competitors in the modern world – or would be if they were not granted special privileges by the state. Most big firms are actually becoming frail, fragile and frightened – of the press, of pressure groups of government, of their customers. So they should be. Given how frequently they vanish – by take-over or bankruptcy, this is hardly surprising. Coca-Cola may wish its customers were “serfs under feudal landlords”, in the words of one critic, but look what happened to New Coke. Shell may have tried to dump an oil-storage device in the deep sea in 1995, but a whiff of consumer boycott and it changed its mind. Exxon may have famously stood out from the consensus by funding scepticism of climate change (while Enron funded climate alarmism) – but by 2008 it had been bullied into recanting.”

Matt Ridley, the Rational Optimist, page 111.

He’s right, of course. While Hollywood moviemakers may delight in using bosses of large firms to be villains, which is rather ironic, given the importance of big entertainment firms like Time-Warner, Disney and Sony Corporation to the movie industry in recent years. The actual track record shows, as Ridley says in this excellent book, that firms have a far shorter shelf life than government agencies. This is hardly surprising. There is, in government, no negative feedback loop with a failed agency or an agency that has outlived whatever reason for its original existence. As we see time and again, a government agency will often look for new things to justify its continued existence, arguing for larger budgets, more staff, and so on. With business, on the other hand, any firm that does not adapt to the constant shifts of consumer habits will die.

Here’s more:

“Half of the biggest American companies of 1980 have now disappeared by takeover or bankruptcy; half of today’s biggest companies did not even exist in 1980. The same is not true of government monopolies: the Internal Revenue Service and the National Health Service will not die, however much incomptence they might display. Yet most anti-corporate activists have faith in the good will of the leviathans that can force you to do business with them, but are suspicious of the behemoths that have to beg for your business. I find that odd.”

After having read and watched anti-business folk for years now, I don’t perhaps find this attitude as odd as Ridley does. The hatred of business is, in my view, a product of centuries of crappy, anti-reason philosophy and a fear of freedom that this has generated.

German politicians view the monetisation of sovereign debt as the road to Weimar. They expect the ECB to be the heir to the Bundesbank and not the Reichsbank

– Willem Buiter, Citigroup chief economist

Estate taxes – or what are called inheritance taxes in the UK – have been an issue in the public sphere lately. Russell Roberts, who writes over at the Cafe Hayek blog – a fine one – has an article criticising such taxes in the New York Times, typically a bastion of Big Government “liberalism” (to use that word in its corrupted American sense). Check out the subsequent comment thread. Here are a couple of my favourites for sheer, butt-headed wrongness:

“There should be 100% confiscation of all wealth at death; except for a family owned business, not incorporated! Passing on wealth is a huge negative for society and probably and even larger negative for those who get the moola; they generally end up with pretty wasted lives! There is no value to passing on wealth except for the egos of the passees!! And there should be a liquidation of all existing foundations, trusts, and other tax avoidance schemes as well! I know so many trustees and administrators who have no economic value whatsoever; and most of these things just perpetuate the arrogance of the founders!”

“chaotican”, from New Mexico.

Here’s another, from someone called “jmfree3”:

Finally, there is the big government is intrusive arguement, which is most commonly made by cold-hearted conservatives (are there any empathetic conservatives or is it wrung out of you all in Young Republican meetings?). Wanting the most greedy people in America to be able to keep the fruits of their greed is not really defensible unless you believe, as most conservatives do, that people who cannot help themselves should be left to die in squalor before the government takes one penny from the more fortunate to help them. Fortunately, liberals care more for there fellow human beings and fight for those who cannot fight for themselves (which is how I know most Democrats in Congress are NOT liberals). After all, isn’t there something in the Bible about “as you treat the least of these”?

Okay, there are other comments from people which are more sensible, such as making the point that there are other examples, besides estate taxes, of taxing people twice. The double-taxation aspect of inheritance tax is not, in my view, the worst thing about it. Rather, it is a tax on the maker of a bequest; it effectively says, “We, the State, are going to ban you from giving all your legitimately owned money to whoever you want, and we demand that a large chunk of it should return to the State that nourishes you and protects you”. If you read the comment from “jmfree03”, that is pretty much what such people believe. They don’t, not in any rooted sense, believe in the idea of private property and respecting the wishes of the owners of said.

Now, of course, the NYT readership is not typical of US public opinion as a whole, if the recent mid-term Congressional elections are a guide. I would also wager that while there has always been a strong egalitarian strain in American life – more so than here – that it has tended to avoid a general denigration of someone just because they are born to rich parents. After all, everyone born in the USA these days is, on this basis, a very lucky person compared with say, someone born in the former Soviet empire, or large bits of Africa, for example.

I remember, many years ago before I started this blogging business, having a chat with Brian Micklethwait and we commented on the size and power of the left in parts of the US, especially in the big universities and other such places. A theory of Brian’s was that it is precisely because the US is so fabulously rich in its mostly capitalist way, that it can afford to support a large class of people inclined to attack it.

It is, of course, ironic that the left supports confiscation of inheritance, since a large element of the left in the US can be described as “trustafarians”; over here, as is sometimes noted, a lot of the Greens – such as Jonathan Porritt or Zac Goldsmith – are born to money and privilege. The Toynbees and the rest are fairly well minted.

Here is one such article here, back in October 2007, that addresses this whole idea that inheriting lots of money gives someone an “unfair” advantage in life over someone else, as if life were like a pre-defined race, such as the Tour de France. But that gets things entirely wrong. It is the fallacy of the zero-sum approach to life generally.

And here is another article by me on the same subject, responding to a letter in the Times (of London) newspaper.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|