We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

… no, I am not talking about his, er, other talents but rather the clarity of his economic analysis…

Ladies and gentlemen, Guido presents the Great Inflation Swindle, we have just seen the second-biggest one-month increase on record and a record high in core CPI yet the Governor of the Bank of England has told us for 3 years inflation was a blip and that the real danger was deflation. It was a deliberate lie to excuse the most reckless monetary loosening since… well actually monetary policy has been too loose globally since back to 1998 when Greenspan “saved the world” after Long Term Capital’s financial theory geeks had a close encounter of the reality kind. The loosening up of monetary policy to smooth the aftermath of that hedge fund collapse told financial risk takers to rack up the risk because central banks would step in if you got in to trouble. Everyone was “too big to fail”. Central bankers turned capitalism from a system of profit and loss into a system of private profits and socialised losses. Taxpayers had their chips put on the gambling table without even being asked.

Read the whole thing.

Here is one of those quotes where you add “read the whole thing”:

But next time you are told that Osborne is imposing savage, reckless cuts on the UK, remember that the figures tell a different story. So far, spending is still going up. The plan is for total spending to go up in cash terms overall this financial year and to fall by 0.6 per cent in real terms (the measure that really matters). This will hurt, especially given that debt interest payments are soaring, reducing the funds available for public services by a lot more than the 0.6 per cent overall cut. But this should also be put into context. Barack Obama, who was in London yesterday, wants to cut public spending by 3.8 per cent next year, more than the 3.7 per cent pencilled in over four years by Osborne. In other words, Obama’s cuts – which many in the US want to make even larger – are four times larger than the average annual cuts proposed by slowcoach Osborne.

So it is no wonder really that the UK’s credit rating was downgraded yesterday by (wait for it) Chinese rating agency Dagong, which cut the UK by one notch to A+, from AA-, and placed it on a negative outlook. You may snigger – but unless the UK is able to deliver on its fiscal austerity not just this year but for the next four, our creditors will soon start panicking again, with good reason.

That’s Allister Heath, writing in the London giveaway newspaper, City A.M., which he edits. His point being that the journey in question has only just begun.

Read the whole thing. The above quote comes at the end. Before that come a few of the facts and the figures.

I suppose the optimistic take on all this is that you can’t wrench a graph that is going up onto a downward path, just like that. But how much wrenching is actually going on?

The main problem with having discussions about economics and financial markets is this: People look at these complex phenomena through entirely different prisms; they use vastly dissimilar – even contrasting – narratives as to what has happened, what is going on now, and what is therefore likely to happen in the future. Citing any so-called “facts” – statistical data, or the actions and statements of policymakers – in support of a specific interpretation and forecast is often a futile exercise: The same data point will be interpreted very differently if some other intellectual framework is being applied to it.

– The opening paragraph of Detlev Schlichter’s latest commentary on the state of the world, entitled Beyond Repair – This will not have a happy ending.

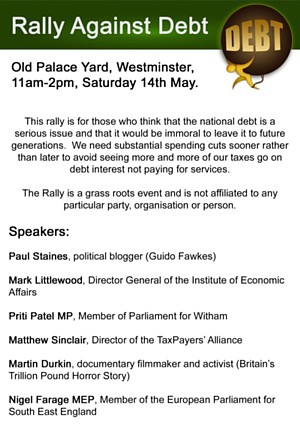

I had already pencilled in the Rally Against Debt as something I would try to be at, if only because it will be taking place a mere walk away from where I live. An incoming email forwarded to me via the Cobden Centre has made this more likely. The email had this attached:

For me, those speakers are an appealing combination of the known, the known of, and the unknown.

How many others will show up, I have absolutely no idea. But, if I can do my tiny little bit to make the turnout that tiny little bit less insignificant, I think that I should. I still promise nothing, but I really will do my best to be there, and then to report back here, hopefully with some photos.

We are already pretty well aware of the case of people such as George Soros – the man credited with helping remove the UK from the European exchange rate mechanism in 1992 – who make a killing from financial markets, while attacking liberal capitalism. Another example is Warren Buffett, the so-called “Sage of Omaha” who, now in his 80s, is one of the world’s wealthiest men with an enviable track record for making money over the long term by what is said to be a ruthless, yet almost heartbreakingly simple commitment to “value investing”.

Over at the Cobden Centre, one of its writers, Detlev Schlichter has an excellent, and measured piece about the Buffett phenomenon. He respects Buffett’s track record (who wouldn’t?), but has this to say:

“So, should we feel sorry for Buffett for being dragged out of his comfort zone of the equity market and being quizzed on everything else? Hell, no. Buffett is a global celebrity and he obviously loves it. These big media events that celebrate him are carefully orchestrated. The tiresome shtick of the loveable everyman from the American heartland who just happens to be a billionaire is a carefully fabricated public image that Buffett uses skillfully to his own advantage – not only to sell shares in his company but – apparently – also to be on good terms with political power. It appears that, while honing his public image of the traditional investor committed to time-tested investment principles, he simultaneously has a big lobbying effort going on Capital Hill, asking for exemptions from collateral requirements for some massive derivative trades his company has made. Maybe it’s time to write another gushing letter to ‘Uncle Sam’?”

“Seriously, I have nothing against the man. I think he deserves admiration for his investment success and he may well be a nice guy. But everything else is show – and probably a cynical show at that. As Porter Stansberry has one of his characters say in this fictional but very illuminating dialogue, Buffett is a member of the establishment and now has a vested interest in the status quo, in government support of the paper money system. But remember that when paradigms shift, fortunes change. When it comes to assessing the future of our monetary system the billionaire and legendary investor may well be wrong. If so, he has the means to survive it but what about the middle-class minions who adore him and follow him blindly and who – I think- he has been lulling into some false sense of systemic stability.”

Here is something by me recently about the Koch brothers, who certainly do support capitalism. And this recently top US banker is probably one of the most hard-core defenders of laissez faire around. A refreshing break from the norm.

Like two drowning sailors hanging onto one another in order to postpone the inevitable, overstretched banks thus accumulate the debt of insolvent governments to keep the façade of solvency up.

– Detlev Schlichter

Yes Lawrence of Arabia is showing on Channel Five, now. I’ve been only half or less paying attention, but I heard this loud and clear:

“Money. It’ll have to be sovereigns. They don’t like paper.”

Said by Lawrence to Allenby, on how to pay the Arabs to fight against the Turks.

He would agree, as would all our mutual friends here.

This is a point of view which is now spreading rather fast.

My Cobden Centre Radio colleague-stroke-boss Andy Duncan is enthusiastic about the latest Keynes v Hayek video. Guido Fawkes already has it up at his blog, and that’s where I’m now watching it.

My first reaction is that Keynes was the bald one, while Hayek had plenty of hair right to the end. This video has it the other way around.

Lots-of-head-hair-to-no-head-hair is one of the most important variables in political propaganda, the bald guy typically being the wicked loser, and the one with the good head of hair typically being the virtuous winner. I therefore deeply regret this particular reversal of the truth. If Keynes had really had lots of head hair, but Hayek very little, fair enough. Hayek would still have been right and Keynes would still have been wrong. But why miss a trick like this, when the truth is on our side?

Otherwise, this video seems pretty good. The important thing is that Austrianism, approximately speaking, must now lose the economic argument and be known by everyone, everywhere, to be losing the economic argument. Austrianism is now being shunned by everyone of any significance in policy-making circles. Right thinking people all now agree that Austrianism is delusional.

And right thinking people are now driving the world economy over the cliff.

For a little more chapter and verse, try reading Detlev Schlichter‘s latest.

When the world economy lies strewn about the landscape at the bottom of the cliff, Austrianism turns around and wins. It reassembles the world economy, and then, slowly at first, but later with gathering strength, drives it back to its former heights and beyond, way beyond.

Well, I like to live in hope.

It’s kind of jumbled, but putting together what the Democrats are saying now and what actually happened in the past, I gather that their economic “plan” is to somehow organize another bubble so that some people will make a lot of money and then tax the hell out of these people, which will then eliminate the deficit and also pay for all their programs, present and future.

– commenter “Hagar” here

This will not surprise some of our regulars here, but I see that Standard & Poor’s, the rating agency has cut the debt rating and outlook for the US. (What kept you? Ed).

I’ll be intrigued as to how cheerleaders for current administration policy, such as Paul Krugman try and spin this. “Those evil bond market vigilantes…”

Time to start dusting off the “D” word.

Update: Talking of defaults closer to home, in Europe, Tim Worstall has been writing that it would be better for countries to openly discuss, and then manage, the chances of default rather than bury their heads in the sand. Meanwhile, Bloomberg columnist Matthew Lynn argues that the demise of the euro can and could be handled much more smoothly than many people believe. I hope he is right.

Another update: Dan Mitchell – of the Cato Institute, talks about lessons from Argentina. Oh great.

“If the Victorians turned up off our shores and threatened me with a gold standard, 7% taxes, property rights, free trade, the right to bear arms, the restitution of double jeopardy, free association, and the right to remain silent, while at the same time guaranteeing the repeal of civil forfeiture and detention without trial, etc., etc., etc., I would welcome them with open arms.”

– Samizdata commenter, John W responding to a point about the supposed evils wrought by the UK on other parts of the world.

A message from the people of Iceland to the global political establishment…

Farðu í rassgat!

By rejecting the absurd notion that governments can legitimately make taxpayers liable for bad commercial decisions by banks, Iceland shows itself as an island of sanity in a global sea of madness.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|