We are developing the social individualist meta-context for the future. From the very serious to the extremely frivolous... lets see what is on the mind of the Samizdata people.

Samizdata, derived from Samizdat /n. - a system of clandestine publication of banned literature in the USSR [Russ.,= self-publishing house]

|

This outpouring of anti-democratic sentiment, this unquestioned faith in the wisdom of the elite over the will of the people, did not begin with the Brexit vote. Through the rise of evidence-based policy and quangos, experts have crept into more and more areas of policymaking. And the sentiment that the masses are a bit thick, brainwashed by the media and stirred up by demagogues, has long greeted every General Election result that doesn’t go the metropolitan elite’s way.

But the Brexit fallout has brought this long unspoken prejudice out of the bistros and into the streets. The idea that the people are effectively incapable of taking part in politics, that you need a PhD in European law to have an opinion on EU membership, is now being shouted from the rooftops and scrawled on placards. Left-wing Remain types, so long the sort who would pretend to speak on behalf of the little people, are now openly calling for elite rule.

– Tom Slater

Tax haven route won’t work for post-Brexit UK, OECD says.

Ok then, making the UK a tax haven is clearly an excellent idea, enhancing competitiveness vs. the rest of the OECD. Of course that could not possibly be why a mouthpiece of the OECD thinks it would be a bad idea, right? Right?

During the course of this splendid campaign, every Ponce in Christendom seems to have stuck his patrician nose about the parapet, sniffed the Great Unwashed and called on the waddling geese of Strasbourg to stand between them and us ruffians. Luvvies and musicians (acting and music being two former escape routes for we chavs now colonised by public school spawn) of course, identity politics social justice warriors (writing the most currently disadvantaged people around – white working class males – out of history, one gripe at a time) naturally. And Eddie Izzard! There have never been a greater number of people I’ve loathed who have been made to cry all at once.

– Julie Burchill

Amidst everything else that’s been going on over the last few days, Britain managed to commemorate the centenary of the first day of the Somme. For those who are unaware of the details 60,000 soldiers of a volunteer army became casualties, 20,000 died while the gains in terms of territory and dead Germans were minimal. While I found most of the commemorations cloying I thought the decision to dress up a bunch of young men in First World War uniforms and strategically position them in our larger cities was an act of genius.

But sadness and horror does not excuse the abandonment of cognitive functions. Many are happy to blame bad generalship and from the sounds of it there was plenty present that day but there were other, deeper, strategic reasons for the disaster.

First of all, Britain was fighting a war in Western Europe against a large, well-equipped and tactically skillful enemy. That is a recipe for a bloodbath. Britain repeated the exercise twice in the Second World War (May 1940 and June 1944 onwards). They were bloodbaths too. We tend to forget that fact because overall the numbers killed in the Second World War were much lower than than the First and because they achieved a succession of clear victories.

Secondly, Britain began the war with a small army. To make a worthwhile contribution Britain was going to have to raise and train a large army. Soldiering, like any other job, is one where experience counts. Anyone who is familiar with the rapid expansion of an organisation will know that this is a recipe for confusion and chaos. In the case of the British army the inexperience existed at all levels. Corporals were doing the jobs of Sergeant Majors, Captains doing the jobs of Colonels and Colonels doing the jobs of Generals. Haig himself (according to Gary Sheffield) was doing jobs that would be carried out by three men in the Second World War. Talking of the Second World War, it is worth pointing out that it took three years for the British to achieve an offensive victory (Alamein) over the Germans which is much the same as the First (Vimy).

Thirdly, Britain began the war with a small arms industry. Expanding that involved all the problems mentioned above plus the difficulty in building and equipping the factories. It comes as no surprise that many of the shells fired at the Somme were duds and even if they were working they were often of the wrong type: too much shrapnel, not enough high explosive.

Fourthly, the Allies needed to co-ordinate. Co-ordinating your efforts means that the enemy cannot concentrate his efforts on one of you and defeat you in detail. This was the thinking behind the Chantilly agreement of December 1915. The idea was that the allies – France, Russia, Britain and Italy – would all go on the offensive at the same time. Russia had done her bit in the Brusilov offensive. Now it was Britain and France’s turn.

Fifthly, the battle of Verdun. It is almost impossible to put into words the desperation of the French army by June 1916. It was fighting against a skillful and determined enemy for what had become sacred ground. It had reached the end of its tether and Britain had no choice but to come to its aid by fighting and thus drawing off the German effort. The original intention was for the more experienced French to have a much larger role at the Somme. Verdun put paid to that which meant that the British had to take the lead. As it happened, the Germans ended offensive operations at Verdun shortly after the battle began.

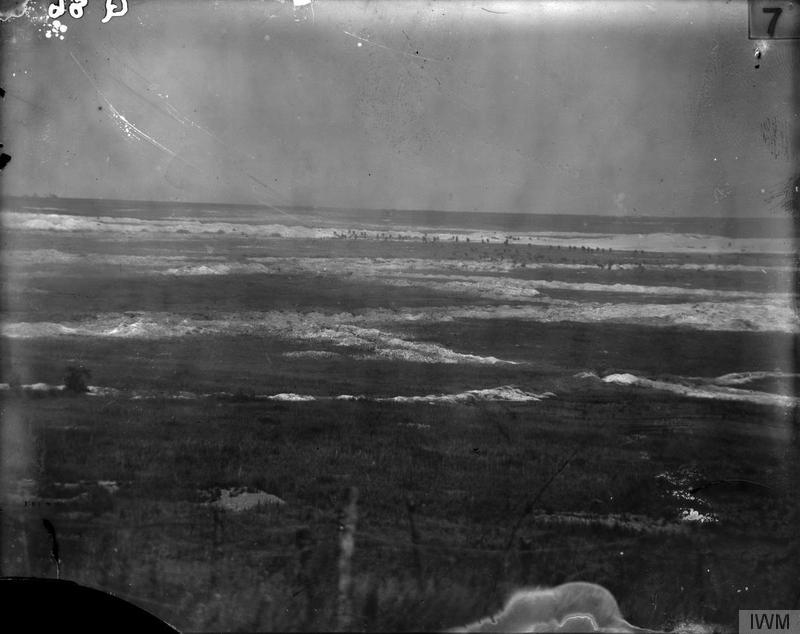

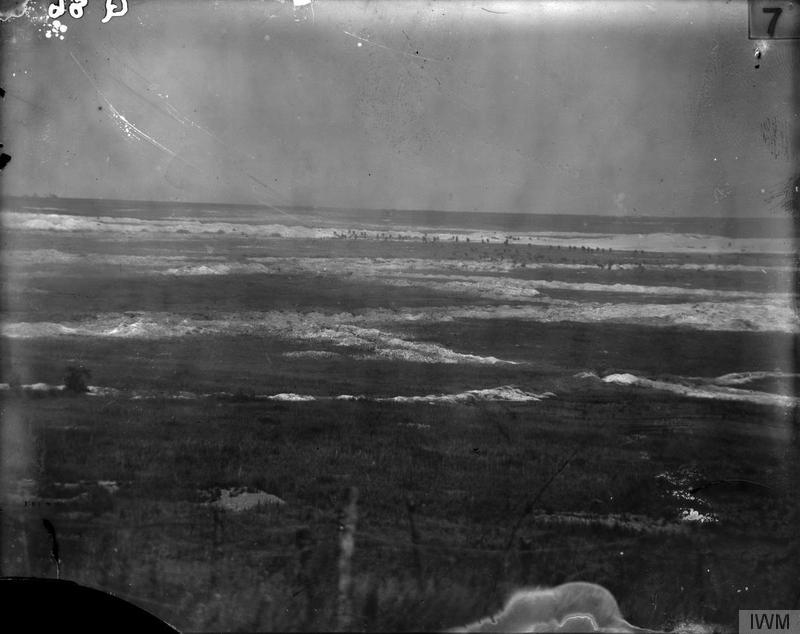

British troops attacking German trenches near Mametz, on first day of the Somme. From here: https://twitter.com/prchovanec_hist/status/749031026039586816

You might think so from reports from the usual quarters, including the Grauniad in a piece, which even by the low standards of legal waffle, is utterly devoid of anything approaching a reasoned legal argument. But from their point of view perhaps, job done.

However, some heavyweight lawyers have weighed in with an opinion piece providing some arguments that Brexit would only be lawful if Parliament approved it. And you can imagine their concern that the clearly expressed will of the electorate might be ignored, why the BBC has even picked up this article, letting it be more widely known.

‘…we argue that as a matter of domestic constitutional law, the Prime Minister is unable to issue a declaration under Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty – triggering our withdrawal from the European Union – without having been first authorised to do so by an Act of the United Kingdom Parliament. Were he to attempt to do so before such a statute was passed, the declaration would be legally ineffective as a matter of domestic law and it would also fail to comply with the requirements of Article 50 itself.’

So that was all a waste of time then, and Mr Cameron has resigned for no good reason (from his pov), I hear no one say.

Let’s look at this a bit, (btw my answer is ‘No’).

Article 50 – The relevant provisions of Article 50 read as follows:

1 Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.

2 A Member State which decides to withdraw shall notify the European Council of its intention. In the light of the guidelines provided by the European Council, the Union shall negotiate and conclude an agreement with that State, setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union. That agreement shall be negotiated in accordance with Article 218(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. It shall be concluded on behalf of the Union by the Council, acting by a qualified majority, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament.

3. The Treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, two years after the notification referred to in paragraph 2, unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period.

Article 50 is part of the Lisbon Treaty, and it is enshrined in law by an Act of Parliament (this Treaty was the one that Mr Cameron gave us that ‘cast-iron’ guarantee of a referendum on, until is was ratified, when it was ‘too late’ to have a referendum.)

Looking at 1, this seems to me to leave the decision to withdraw to the member state, and for it not to be a matter for the EU, and nothing more. If a member state decides to leave, it need only follow its own requirements, i.e. the EU does not presume to over-ride any such mechanism, fair enough, and the decision itself must be lawful, lest a would-be dictator seeks to rush out of the EU on the way to mimicking Belarus.

2 sets out the mechanism for the departing State to notify the European Council. Nothing fancy there, a verbal statement could do it, but a handwritten letter would be polite. “Dear Donald, We are ducking out of the European Union in accordance with the terms of Article 50, this letter is our formal notification thereof, Chauzinho, signed ….”. And then a negotiation starts.

Looking at 3, the Treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question etc. from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement (whenever that might be) or, failing that, 2 years after the notification, unless the European Council unanimously* decides to extend this period (in agreement with the departing state)

(*Pay attention folks, 50 (3) crops up below.)

So if nothing is agreed to extend time, or if we don’t leave earlier, exit is automatic after 2 years. Perhaps the Chilcott committee will find a new task for the next decade or so, negotiating Brexit?

The problem, it seems, is that the lawyers think that the Royal Prerogative is constrained by law, in that the Sovereign (on the advice of her Ministers) can do no wrong, but also cannot do anything that is unlawful such as exercising her Prerogative when Parliament has provided for it to be exercised in a particular way or with prior Parliamentary approval, in which case it is no Prerogative at all, of course.

All very well, but the exercising of Article 50 is simply doing what ‘it says on the tin’, the right to withdraw is inherent in the Treaty, so exercising a right provided for in the Treaty is not (well it seems fairly obvious to me anyway) a breach of the Treaty or of EU law. One might ask, if Article 50 does not allow for withdrawal, what on Earth does it provide for?

But of course, it goes much deeper than that, the exercise of the Prerogative is constrained by Parliament and the law. The first line of attack is to argue that Parliament has to approve a decision to leave the EU.

Is this found in 50 (1) “…in accordance with its own constitutional requirements…” Of course, the UK has no written constitution (moan the Lefties), but the referendum was held by authority of an Act of Parliament, and it was only ever ‘advisory’, i.e. it was legally a pointless exercise, as the outcome mandated nothing, whereas a 2011 Referendum did mandate a change in the law in the event of approval to changes in the voting system, by delegated legislation within the Act. So the Act that provided for this Referendum could have provided for a mechanism for its implementation by its own provisions mandating the Prime Minister to trigger article 50 in the event of ‘Leave’ prevailing, or by requiring another Act (which is necessarily subject to Parliament’s will) to trigger Article 50. The Prime Minister may ignore this Referendum outcome completely, of that there is no legal doubt.

But then again, Parliament has constrained the power of the executive (i.e. the Crown as advised) in relation to treaties. Step forward The European Union Act 2011. This Act is a sort of ‘entrenching’ Act, which sets out various obstacles to Treaty modifications without a referendum in the UK, see section 4.

4 Cases where treaty or Article 48(6) decision attracts a referendum

(1) Subject to subsection (4), a treaty or an Article 48(6) decision falls within this section if it involves one or more of the following—

(a) the extension of the objectives of the EU as set out in Article 3 of TEU;

(b) the conferring on the EU of a new exclusive competence;

(c) the extension of an exclusive competence of the EU;

(d) the conferring on the EU of a new competence shared with the member States;

(e) the extension of any competence of the EU that is shared with the member States;

(f) the extension of the competence of the EU in relation to—

(i) the co-ordination of economic and employment policies, or

(ii) common foreign and security policy;

(g) the conferring on the EU of a new competence to carry out actions to support, co-ordinate or supplement the actions of member States;

(h) the extension of a supporting, co-ordinating or supplementing competence of the EU;

(i) the conferring on an EU institution or body of power to impose a requirement or obligation on the United Kingdom, or the removal of any limitation on any such power of an EU institution or body;

(j) the conferring on an EU institution or body of new or extended power to impose sanctions on the United Kingdom;

(k) any amendment of a provision listed in Schedule 1 that removes a requirement that anything should be done unanimously, by consensus or by common accord;

(l) any amendment of Article 31(2) of TEU (decisions relating to common foreign and security policy to which qualified majority voting applies) that removes or amends the provision enabling a member of the Council to oppose the adoption of a decision to be taken by qualified majority voting;

(m) any amendment of any of the provisions specified in subsection (3) that removes or amends the provision enabling a member of the Council, in relation to a draft legislative act, to ensure the suspension of the ordinary legislative procedure.

Zzzzz…. But nowhere in this Act has Parliament put any brake on the exercise of the notification to leave the EU under Article 50! That right is left untouched, yet it could have been constrained. Furthermore, this Act requires a referendum on certain decisions by Ministers (i.e. the Crown) by Section 6.

6 Decisions requiring approval by Act and by referendum

(1) A Minister of the Crown may not vote in favour of or otherwise support a decision to which this subsection applies unless—

(a) the draft decision is approved by Act of Parliament, and

(b) the referendum condition is met.

(2) Where the European Council has recommended to the member States the adoption of a decision under Article 42(2) of TEU in relation to a common EU defence, a Minister of the Crown may not notify the European Council that the decision is adopted by the United Kingdom unless—

(a) the decision is approved by Act of Parliament, and

(b) the referendum condition is met.

(3) A Minister of the Crown may not give a notification under Article 4 of Protocol (No. 21) on the position of the United Kingdom and Ireland in respect of the area of freedom, security and justice annexed to TEU and TFEU which relates to participation by the United Kingdom in a European Public Prosecutor’s Office or an extension of the powers of that Office unless—

(a) the notification has been approved by Act of Parliament, and

(b) the referendum condition is met.

(4) The referendum condition is that set out in section 3(2), with references to a decision being read for the purposes of subsection (1) as references to a draft decision and for the purposes of subsection (3) as references to a notification….

Try an espresso to stay with me, but furthermore, the Schedule to this Act sets out ‘Treaty provisions where amendment removing need for unanimity, consensus or common accord would attract referendum’.

And here we find, at the bottom, Article 50 (3):

Article 7(2) (determination by European Council of existence of serious and persistent breach by member State of values referred to in Article 2).

Article 14(2) (composition of European Parliament).

Article 15(4) (decisions of European Council require consensus).

Article 17(5) (number of, and system for appointing, Commissioners).

Article 19(2) (appointment of Judges and Advocates-General of European Court of Justice).

Article 22(1) (identification of strategic interests and objectives of the EU).

Chapter 2 of Title V (specific provisions on the common foreign and security policy).

Article 48(3), (4), (6) and (7) (treaty revision procedures).

Article 49 (application for EU membership).

Article 50(3) (decision of European Council extending time during which treaties apply to state withdrawing from EU).

So Parliament has set limits on what Ministers of the Crown may do in respect of the Lisbon Treaty, and has said nothing at all about the exercise of the right to withdraw requiring Parliamentary approval, it has left this area alone. Yet, if the UK were to partake in a decision to change the requirement for unanimity from the European Council when extending time during which the withdrawal mechanism applies to a departing state, this would require a referendum.

Of course, triggering Article 50 and Brexit will still leave Section 2 (2) of the European Communities Act 1972 intact and in force, maintaining the supremacy of EU law in the UK after Brexit, because nothing in Article 50 dis-applying the Treaties would necessarily repeal that section of UK law. But that would leave a post-Brexit Parliament in the odd position of being bound by a predecessor Parliament’s decision to make EU law supreme and limit its power to amend EU law. Would anyone suggest that such a situation would last?

The final arguments against Brexit may well be that to leave the EU is a breach of someone’s Human Rights, and is therefore void or should be stopped, or, alternatively that the decision to leave is a breach of EU law and therefore void.

But of course, by the very nature of the EU, the UK’s courts, even if they were minded to grant an injunction or interdict against notification of Brexit (making it void) cannot constrain the EU or stop it from doing what it wishes, such as showing us the door.

UPDATE 19072016: Court challenge to be heard in the High Court of England and Wales in October 2016.

Brave Sir Boris ran away

Bravely ran away away

When danger reared its ugly head

He bravely turned his tail and fled

Yes, brave Sir Boris turned about

And gallantly he chickened out

Bravely taking to his feet

He beat a very brave retreat

Bravest of the brave, Sir Boris!

(h/t commenter Pardone)

…indeed, praise him to high heaven. And then when (if) you become Prime Minister, make your first order of business to knife the idiot and fire him.

Get rid of any REMAIN supporter in sensitive jobs, and the sooner you do it, the quicker the new order becomes the new orthodoxy. Anyone who was a party to Project Fear must go!

What’s on the menu when bishops gather for a Brexit breakfast at Lambeth Palace following Britain’s historic vote to leave the European Union? Egg on face. Mitres in sanctimonious sermon sauce. Burnt reputations on French toast. Honeyed Brussels rhetorical waffle. Side dish for guest invitee Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church—haggis with a dash of hogwash. Breakfast includes two archbishops’ specials: a Sentamu special—sausages stuffed with pious platitudes and a Welby special: Eton mess.

– Rev. Jules Gomes, pastor of St Augustine’s Church, Douglas, on the Isle of Man.

I strongly recommend this article to our readers, for not only is it intermittently hilarious, it is totally on the money.

First, Brexit means Brexit. The campaign was fought, the vote was held, turnout was high, and the public gave their verdict. There must be no attempts to remain inside the EU, no attempts to rejoin it through the backdoor, and no second referendum. The country voted to leave the European Union, and it is the duty of the government and Parliament to make sure we do just that.

– Theresa May

May is currently the front-runner to be the next Prime Minister.

With the Brexit vote of last week continuing to send shockwaves through the corridors of power (does that mean those corridors are vibrating, door handles jiggling and lights flickering?), one argument I have seen break out is of how the UK will, without being in the mighty, efficient and effective mechanism of the EU, be able to work out a deal. (If you are detecting a touch of sarcasm, you are correct.) For example, on a social media exchange, a person earnestly exclaimed that the UK can’t possibly arrange a free trade agreement (FTA) with India because the Indians just won’t, just won’t agree on one with us, because, well, they won’t. A stock argument goes that if the UK leaves the EU, then depending on whether it does or does not retain Single Market access, like Switzerland, other countries will be reluctant to trade with the UK. Why? Because the only reason, it is said, that people want to engage with the UK is because it gives access to the rest of the EU. The UK is, on this argument, nothing more than a conduit, an entrepôt, for Europe. The fact that another country might want to deal with the world’s fifth-largest economy on its own right is scarcely entertained.

Funnily enough, last year I recall reporting on how Australia, which for some crazy nationalist reason isn’t in the EU, signed a trade deal with China, which much to its shame, isn’t in the EU either. China is the world’s second-largest economy; Australia is some way down the order but still relatively significant. These two nations signed a deal. It was done without all the structures of a transnational organisation. This is an event that, for quite a lot of people, is unthinkable, like a decent summer in England.

Another option for the UK is to simply declare unilateral free trade, rather than wait for some grand negotiation with the EU over access. There is a consideration of this approach at Econlog here:

But if the new British prime minister want to puzzle and indeed shock its European counterparts, this may well be the best option. Go ahead and zero tariffs on imports coming from the EU. It might well be one of those very few choices that could prove to be economically beneficially in the long run, not least because it will minimize the problem of capture by special interest groups when it comes to trade policy. But it may prove to be expedient from a political perspective too. As the government should run through the Houses its proposed “interpretation” of the vote (which was, after all, a consultative referendum), open support for free trade may help, in the short run, to restore peace and harmony among the Tories. On top of this, it might give the UK a strong card in negotiations with the EU, making retaliatory attempts hard to “sell” to the public.

And here is Tim Worstall on the same subject:

The entire point of trade is that we can get our hands on what they make: so why would we ever want to have anything other than unilateral free trade? Why would we impose tariffs on the very things we want and make them more expensive for ourselves?

Sure, other people might impose tariffs on our exports. But that means that they are making themselves poorer by not having tax free access to the lovely things that we can make cheaper or better than they can. As Joan Robinson was fond of pointing out, tariffs are like throwing rocks in the harbour to make imports more difficult. And just because you are throwing rocks in your harbour there’s no reason I should throw rocks in my own. To do so just makes me worse off and why should I do that?

As I have said recently, one of the excellent consequences of Brexit is that it rends apart many of the lazy assumptions that give rise to transnational organisations, as well as the assumptions of the sort of people who prosper in working for them. It makes us think again about what sort of rules and regulations, if any, are needed so that human beings can trade. And those of a classical liberal disposition need to take the lead in pointing out that ultimately, countries don’t trade, individuals do. Any attempt to interfere with such transactions is ultimately about Person A being prevented from transacting with Person B on terms to their liking.

Maybe it is also time to dust of the speeches and writings of Richard Cobden.

Brendan O’Neill, the editor of the publication Spiked, and who is an ardent Leaver when it comes to the European Union, has been writing about how the exit vote last week can be largely explained in terms of class and attitudes of elites. (O’Neill is, or is recovering from being, a Marxist, so his economics still seems a bit suspect to me, even though I like the cut of his jib generally, especially on other issues around liberty and government).

I think the class analysis has some validity; it is worth noting that there is more to class-based interpretations of what is going on than the Marxian version. There are, in the classical liberal/conservative traditions of political philosophy and approach, uses of class as a way of seeing how the world works. One person’s essay that I am reminded of is the famous one by William Graham Sumner, The Forgotten Man. Or perhaps a riff on the same tune is Nixon’s “great silent majority”. These approaches aren’t really about proletarians versus “bosses”. They are, in my view, more about those who are broadly self-reliant, deriving the bulk of their earnings from their own efforts and who aspire to have, and retain, capital, and those who do not. The latter can be those who subsist on state benefits, or grander folk working in the public sector paid for largely by the first group. (There are fuzzy boundaries between all types.) And I think that sort of split maps better in explaining whether you are going to be liberal or protectionist, for a big State or a smaller one. But it doesn’t necessarily help on explaining all the voting on the Brexit debate. I wrote this in response to one of O’Neill’s posts on Facebook, and I reproduce it here with some light edits:

I am not sure how far the class-based analysis can be made to work in terms of having a causal effect (remember that old warning about correlation and causation). Whether used in a Marxian or other sense, class can explain some of the differences, but some of the arguments cut across. I am middle class, working in the media covering private banking and wealth management around the world. My job takes me to the continent a lot, as well as Asia, the US, and Middle East. Some of the people I work with are from continental Europe. I am relaxed – mostly – about free movement of labour. I went to a good state school, went into higher ed. in the 1980s, my late mother was posh, my old man was a grammar schoolboy who later became a farmer and is comfortably off. I like classical music, fine art, French wine and sailing. So from a lot of points of view I am “middle class”. And I voted Leave. To some extent I “voted my wallet”, not, as might be the case with someone from the old industrial north, because I was worried about “cheap labour”, or had some notion that this will “save the NHS” or suchlike, but because I want the UK to have the freedom to negotiate new economic links outside the EU to hedge this country’s economy against the weakness, and possible crisis, in the eurozone. I am on the free market, libertarian end of the political and philosophical spectrum. I therefore loathe the unaccountable, nanny tendencies of the EU, and think my values will flourish if we leave.

|

Who Are We? The Samizdata people are a bunch of sinister and heavily armed globalist illuminati who seek to infect the entire world with the values of personal liberty and several property. Amongst our many crimes is a sense of humour and the intermittent use of British spelling.

We are also a varied group made up of social individualists, classical liberals, whigs, libertarians, extropians, futurists, ‘Porcupines’, Karl Popper fetishists, recovering neo-conservatives, crazed Ayn Rand worshipers, over-caffeinated Virginia Postrel devotees, witty Frédéric Bastiat wannabes, cypherpunks, minarchists, kritarchists and wild-eyed anarcho-capitalists from Britain, North America, Australia and Europe.

|